World Championships: What Gatlin v Bolt means for athletics

- Published

Justin Gatlin is favourite to win double gold at the World Championships

IAAF World Championships on the BBC |

|---|

Venue: Beijing National Stadium Dates: 22-30 August |

Coverage: Live on BBC TV, Red Button, Radio 5 live, online, mobiles, tablets and app. |

Usain Bolt v Justin Gatlin is being billed by some as a battle for the soul of athletics.

Jamaican Bolt is the hero, a record-breaking global superstar and the sport's poster boy, having won six Olympic gold medals.

Gatlin is his prospective nemesis, a 33-year-old American who has been banned twice for doping offences but is now running faster than ever.

Some argue a Gatlin gold at the Bird's Nest - he takes on Bolt in the 100m and 200m - would be a crushing blow for athletics, a sport plagued by a succession of positive drugs tests and allegations of further widespread doping.

His mere presence in China is already creating negative headlines.

What did Gatlin do?

In 2001, when he was still at college, he was given a two-year suspension for taking a banned amphetamine.

Usain Bolt v Justin Gatlin at the World Athletics Championships

He successfully argued this was due to medication he took for attention deficit disorder and was allowed to return to competition after just a year.

Then, in 2006 - having won the 100m and 200m double at the 2005 Worlds in Helsinki - he tested positive again, this time for testosterone.

Gatlin: the case against |

|---|

Gatlin was banned for eight years, avoiding a lifetime ban in exchange for his co-operation with doping authorities.

He appealed again and had his suspension cut in half, to four years.

So he has served his punishment?

Yes. But there are some who think he should have been banned for life - the usual punishment for athletes who test positive twice.

There is also research, by scientists at the University of Oslo, that suggests athletes who take anabolic steroids still benefit years later.

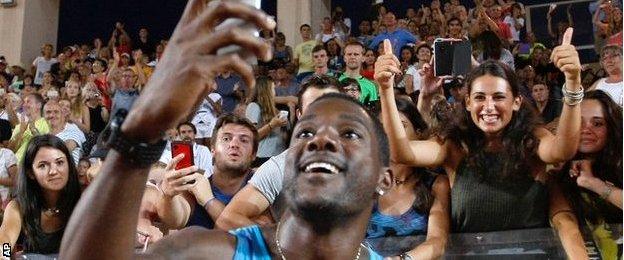

Gatlin has often proved a hit with spectators, spending time taking selfies with them

That only fuels the anger of those people who believe dopers should never be allowed to compete again.

Gatlin's agent, former world record 110m hurdler Renaldo Nehemiah, admits his runner "will never" be forgiven by some people.

But the crowds who watch Gatlin race seem to like him. He is regularly asked for selfies, while his laps of honour can last 45 minutes.

But why is he so despised?

Because he has never accepted he did anything wrong and because he has a very real chance of winning in Beijing.

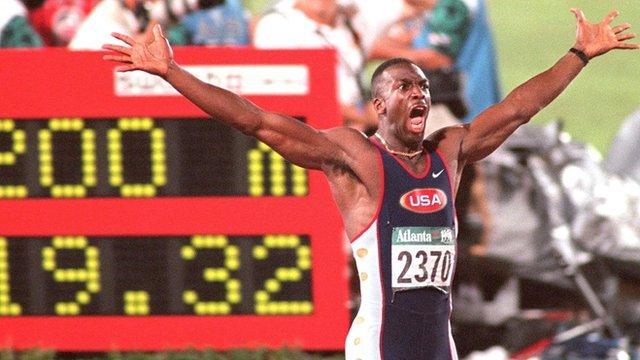

But there's more to it than that. A decade ago, athletics was recovering from the Balco scandal., external

High-profile athletes like Marion Jones, Tim Montgomerie and Dwain Chambers were all found to have been using so-called 'designer' steroids that had previously been undetectable.

At the time, Gatlin was being marketed as the young, clean face of the sport. Then he tested positive for a second time.

Gatlin has always maintained he was the victim of sabotage, alleging that his massage therapist Christopher Whetstine, who denies Gatlin's claims, applied a cream that resulted in the positive test.

What does Gatlin think of it all?

The man himself says he is fed up with the constant questions about his doping past and finds criticism from fellow athletes particularly difficult to take.

On suggestions his rivalry with Bolt is a battle between good and bad, he is insistent: "I am just a runner like he is a runner.

"There is no good runner or bad runner. We are just runners. No-one is trying to take over the world. No-one is trying to blow up the world."

In June, he told the BBC that no-one was complaining that much when he returned to competition in 2010 and argues that he is only a target now because he is running faster than ever and winning races.

Is it time to cut him some slack?

Some say it is, like former world 100m champion Kim Collins.

The St Kitts and Nevis sprinter argues that even murderers are allowed back into society after serving their sentences - so why is Gatlin getting a hard time?

Others, like Olympic discus champion Robert Harting, have made it clear they believe Gatlin is a huge liability for athletics.

Harting took decisive action to show his disgust with the IAAF and Gatlin

The German asked to be removed from a list of candidates for the IAAF's male athlete of the year award in 2014, arguing it was "insulting for me and my fans" to be on the same list as a "doping offender".

Equally outraged is former British heptathlete Kelly Sotherton, who won Olympic bronze in 2004 and World bronze in 2007.

More from BBC Sport |

|---|

"I really cannot stand the guy," she said. "It's not because he's cheated twice it's because he is unrepentant. He is so arrogant about it and doesn't care. I don't hate many people but I really hate him."

Former world 1500m champion and BBC commentator Steve Cram is not quite as outspoken on the subject of Gatlin but admitted it was "very difficult to be enthusiastic about someone like him".

Back in the United States, however, Larry Eder, the publishing director of respected athletics websites The Running Network and Run Blog Run, says most Americans are willing to give Gatlin "a second shot".

One of those is US Paralympic 100m world record-holder Richard Browne, who says he thinks Gatlin is "great for the sport" because he is "tired of Usain Bolt just demolishing everybody".

What does Bolt think?

The reigning world and Olympic champion at 100m and 200m is attempting to steer a diplomatic course, insisting he has "no problem" racing Gatlin.

But he continues to face questions about the American and the issue of doping in general.

Speaking to the media in Beijing on Thursday, he said it was "sad" the focus seemed to be on the issue of doping in the days before the start of the World Championships.

Bolt is perhaps the most recognisable figure in athletics, and the sport's most reliable promotional tool but, when it comes to the fight against the dopers, he insists he is not its "saviour".

He says "it's the responsibility of all athletes, not just me" to take on the dopers.

What's the IAAF's stance?

Given Gatlin has served his time, there is little the International Athletics Association Federation can do, as the world governing body's new president Lord Coe has admitted.

Speaking before his election, Coe told the BBC he was "uncomfortable" that convicted dopers were allowed to compete.

New IAAF president Coe has promised to clamp down on doping

But he added: "If they win, they need to be accorded the same respect anyone else would in that field."

What the IAAF, which organises the World Championships, has done is try to limit the damage it could potentially suffer should Gatlin top the podium in Beijing.

A new rule means that, even if he wins gold, Gatlin won't be eligible for the athlete of the year award. Nor will anyone else adjudged to have committed a serious doping offence.

Would a Gatlin win really be that bad?

If he wins, any reports will inevitably reference his past, overshadowing both his achievement and the championships themselves.

It could be a PR disaster.

Britain's Darren Campbell, an Olympic 200m silver medallist, has a different view, however.

He argues that a Gatlin victory could be good because it would force the IAAF to think long and hard about how it deals with dopers in the future.

"In a crazy kind of way, I want to see Justin Gatlin beat Usain Bolt because the sport will have to deal with it," he said.

Finally, will Gatlin win in Beijing?

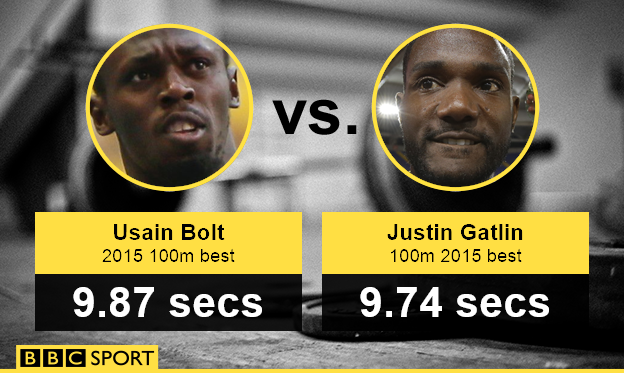

Gatlin hasn't lost over 100m or 200m since 2013 and has set personal bests for both distances - 9.74 seconds and 19.57 seconds - this season.

In fact, he has clocked the four fastest 100m times of 2015:

9.74 - 15 May

9.75 - 4 June

9.75 - 9 July

9.78 - 17 July

That said, he hasn't raced Bolt over either distance since they met in the last World Championships final two years ago.

Until Bolt ran 9.87 seconds twice at the Anniversary Games in London in July, Gatlin was the clear favourite for double gold in Beijing.

But now Bolt is showing signs of form after injury blighted his 2014 season and the start of 2015, the race for gold is not so clear cut.

It would be foolish to write off Bolt if any case, argues Jamaican team-mate Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce.

"Look at this way," said the double Olympic 100m champion. "He has run 9.5. Nobody has gone close to 9.5. Let's see."

- Published21 August 2015

- Published7 October 2014

- Published30 August 2015

- Published8 February 2019

- Published10 September 2015

- Published21 August 2015

- Published20 August 2015