Olympic medals: The tricky job of reallocating - and getting them back

- Published

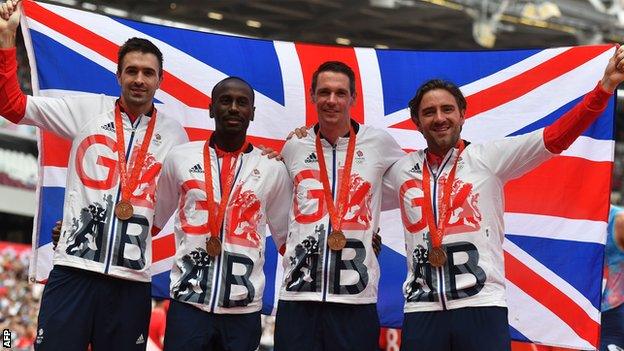

Great Britain's relay team receive their Beijing bronze medals

Gone are the days of Olympians receiving their medals in an airport food court,, external or having to hold their own medal ceremony., external

Britain's 4x400m relay squad from the 2008 Beijing Games got their podium moment in front of a home crowd at the London Anniversary Games last month, finally becoming Olympic medallists after a nine-year delay.

They are among dozens of athletes who are receiving medals after their competitors were disqualified retrospectively and stripped of their achievements because of doping offences.

The new approach of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), as part of a stated commitment to supporting clean athletes, is to "honour accomplishments in a more systematic manner".

That has been reflected at the World Athletics Championships, where 16 medals were reallocated at the recent meet in London, with Britain's Jessica Ennis-Hill receiving her gold from Daegu in 2011.

Medal reallocation is not a quick and easy process. It is a minefield of retests, appeals and constant calls for disqualified athletes to return their medals, which can sometimes fall on deaf ears.

The Russian Athletics Federation has been asking for 24 Olympic medals to be returned by their athletes. To date, just three have heeded those requests.

If all else fails it seems, the IOC just makes a new batch of medals, as happened in the case of the British 4x400m relay quartet.

Why is this happening?

The Russian doping crisis has dominated athletics since it was uncovered in 2014.

It culminated in Russian track and field athletes being banned from competing at Rio 2016 by the IAAF - athletics' world giverning body - after widespread, state-sponsored doping was uncovered in the country.

The IOC retested hundreds of samples from the 2008 and 2012 Olympic Games, using new methods to uncover banned substances that would have gone undetected at the time, covering a number of sports.

As of April 2017, 1,053 samples were retested from Beijing, resulting in 65 sanctions, while 492 samples were reanalysed from London, with 41 sanctions.

The Russians have taken the headlines recently, with eight disqualified from Beijing and nine from London - some pending appeals.

But going as far back as the 1984 Olympics, in athletics alone, athletes from a total of 11 countries have been disqualified and asked to hand back their medals.

'We all felt funny about that race'

Russia's Maksim Dyldin, Vladislav Frolov, Anton Kokorin and Denis Alekseyev finished third in the 4x400m relay at the 2008 Beijing Olympics

On 23 August 2008 in Beijing, Michael Bingham, Martyn Rooney, Robert Tobin and Andrew Steele ran a season's best time of two minutes 58.81 seconds to finish fourth, external - 0.75 seconds behind third-placed Russia in the Bird's Nest stadium.

No quartet had ever run so fast but failed to win a medal.

"We all felt funny about it, felt it wasn't quite right and something didn't add up," Steele told BBC Sport. "It was a big shock for us."

Then, in May 2016, the IOC informed the Russian Olympic Committee (ROC) that 14 Russian athletes were suspected of doping at the Beijing Games.

And in July 2016, 4x400m runner Denis Alekseyev told Russian news agency Tass, external that one of his samples had tested positive.

But it was two months later - on 13 September - that the IOC finally confirmed that the banned anabolic steroid turinabol had been detected in Alekseyev's sample.

The Russian team were disqualified from the 4x400m relay and ordered to hand back their bronze medals, diplomas and medallist pins, with the ROC tasked with ensuring their return "as soon as possible".

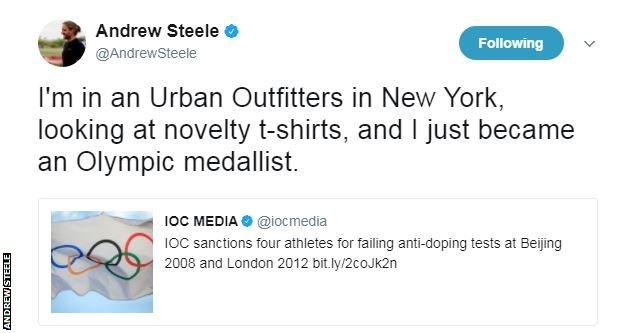

A tweet that changed everything

Steele was shopping in New York when he saw the news break on Twitter.

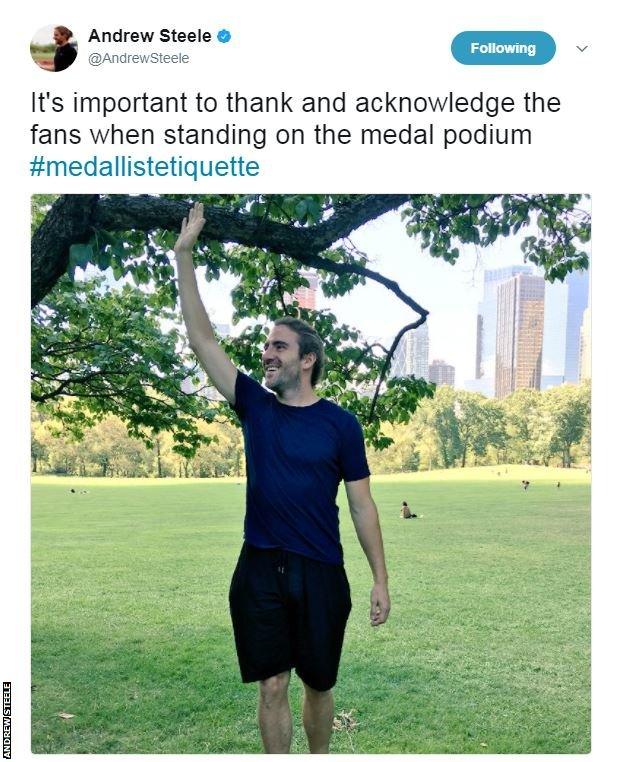

Andrew Steele held his own 'medal ceremony' in Central Park

"It was just a relief to get official confirmation," he said. "That press release was the first I had seen. I had been hearing that this might happen and even a year before there were rumours.

"But I couldn't understand why they had not detected the substance in 2008."

Bans, appeals and a stock of blank medals

Alekseyev's disqualification was the start of a nine-month process for Steele and his team-mates to receive their bronze medals.

The 29-year-old Russian, who already served a two-year ban for another doping offence in 2013, was suspended for four years by the Russian Athletic Federation (Rusaf) in June 2017 for his Beijing infraction. He will be able to compete again from 15 November 2018.

Rusaf had appealed, external for the return of medals in February 2017, at a time when only Kokorin - who himself was not guilty of doping - had handed his back.

Kokorin, 30, did so in December 2016 and a press release at the time from Rusaf said: "The athlete confirmed adherence to the Olympic ideals and observance of the rules of the IOC."

Under IOC rules, the reallocation of medals takes place when "athletes/teams sanctioned have exhausted all their remedies of appeal and when all procedures are closed".

Medals are usually returned to the National Olympic Committees concerned, which sends them back to the IOC.

Team GB confirmed on 21 June of this year that they had finally received, external the medals from the IOC, but the ones handed to Steele and his team-mates were not the ones that Alekseyev and the Russians were given in Beijing.

To date, Kokorin remains the only member of the disqualified Russian relay quartet to have returned his medal.

The IOC told BBC Sport that four new medals were used to avoid delaying the award ceremony.

"The IOC has got a stock of blank medals for after the Olympic Games and those are engraved at request when it is justified," the IOC said in a statement.

An Olympic medallist... nine years later

Andrew Steele (right) and the men's 4x400m relay bronze medallists

It did not matter to Steele and his team-mates that the medals were not the original ones.

"It is nice to be able to say I am an Olympic medallist," said the Briton, who only found out he would be awarded the medal two weeks before the ceremony.

"In the rest of my career, I never got near a podium. It is shame I did not get to experience that at the time, but this was vindication - it means my career was not a waste of time, money and health.

"Having that medal makes it much more real, to actually own this item."

The Team GB quartet were greeted to a rousing reception from the home crown inside the London Stadium, something Steele describes as "surprisingly poignant".

He references the fact US shot putter Adam Nelson was given the Athens 2004 gold medal denied to him by drugs cheat Yuriy Bilonoh by a US Olympic Committee official at an airport food court, external eight years after the event.

He added. "It was the only podium moment I had in my career and I think I appreciated it more than if I had been younger. I am happy they made a fuss and it was the right thing to do. I guess, in retrospect, it all worked out in the end. "

Steele, 32, spent three years after Beijing struggling with injuries and glandular fever and ultimately missed out on a place at London 2012, finally retiring last year.

He added: "It is a shame we did not get it the medal at the time. It would have been an interesting change in my life trajectory because my career went downhill after that.

"If I had won a medal, it would have guaranteed four years of support. But I got ill with glandular fever and was forced to make sure I ran, as I was worried about my salary and income.

"Athletics became a job and I made myself worse. That may not have happened had I had four years of support."

However, Steele refuses to blame Alekseyev, saying he does not think the Russian had "bad intentions". Another of the Russian quartet - Dyldin - was also subsequently given a four-year doping ban., external

"The Russians are good athletes and great guys but the real shame is that the wrong methods are being forced on them," he said.

"There is evidently a different approach to doping and the most upsetting thing is that the doping is from the boardroom level down, not just an individual cheating. When it comes from the men in suits, it is more worrying. "

And what about the rest?

Russia says some athletes' cases are still under consideration, so decisions have yet to be made about their reallocation.

Kokorin aside, Natalia Antukh returned her 4x400m silver from 2008 and Aleksandra Fedoriva-Shpayer gave back her London 4x100m relay gold.

None of that trio have been convicted of doping themselves, but were part of relay squads in which a team-mate has.

A further eight athletes are in the same situation, but have not returned their medals. And none of the 13 athletes disqualified for failing retests of their samples have handed back theirs.

The IOC says the reallocation process is not automatic and is done on a case-by-case basis. It says it is working closely with the ROC to make sure that all medals that have to be reallocated are returned in due course.

There are a further seven Olympic athletics medals reallocations under appeal.

That includes the potential British bronze medals from 2008 of Kelly Sotherton in the heptathlon and Goldie Sayers in the javelin, with appeals ongoing for Tatyana Chernova and Mariya Abakumova respectively.

- Published13 August 2017

- Published3 March 2018