Jessica Ennis-Hill: A personal guide through the magic of Olympic gold

- Published

- comments

Olympics Rewind: Jessica Ennis-Hill wins heptathlon gold in London

In that snapshot, Jessica Ennis-Hill looks serene.

A few metres behind her, her rivals are stretching and straining for the finish line. Tatyana Chernova's face is a picture of pain.

Ennis-Hill is ahead, untouchable. With the roars of 80,000 fans ringing in her ears, with her eyes facing skywards and her arms aloft, she is at peace.

"In that moment I had no control. I was finally free," Ennis-Hill says now, looking back on her crowning moment from London 2012. That dominant victory in the 800m, the seventh and final event of the heptathlon, was the moment she won Olympic gold.

"I had never celebrated across the finish line before," remembers the 34-year-old. "And I never really had a plan to celebrate in London.

"But it was pure relief. It felt like I'd been holding my breath through the whole two days."

She wasn't the only one.

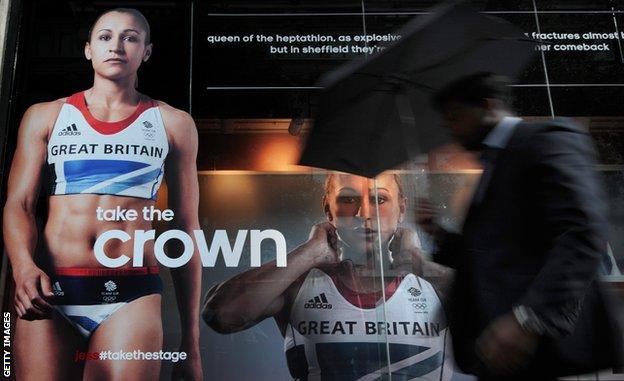

In the build-up to the 2012 Olympics, Ennis-Hill was the undisputed 'face of the Games', the woman charged with delivering London's 'Cathy Freeman moment'.

Mo Farah and the men's rowing coxless four shouldered a similar burden as pre-event favourites. But they didn't carry the weight of a nation in quite the same way. Finishing second was nowhere for Ennis-Hill. If you believe her long-time coach Toni Minichiello, all it took was 12.54 seconds to show that was never going to happen.

The heptathlon is like a boxing bout which goes the full 12 rounds. Two 12-hour days of competition featuring seven gruelling events. In Minichiello's view, the knockout punch came in round one: the 100m hurdles.

The morning of Friday, 3 August was sunny and bright, a good start for Ennis-Hill. Potential for inclement British weather had given her sleepless nights in the build-up.

While forcing down a big breakfast in the Olympic village - coffee, banana, cereal, toast and yoghurt - support staff were trying anything to distract her. "Making jokes and trying to act like it wasn't the biggest day of our lives," as she says.

The illusion would soon be shattered spectacularly.

Advertising bill boards across Britain featured Ennis-Hill as the 'face of the London 2012'

Before the Games, Ennis-Hill had received hundreds of invites to sponsor events at the Olympic Stadium. She turned down every one.

"I said no to everything because I didn't want it to become a really familiar place to me," she explains. "I wanted it to be really fresh, really new. Really adrenaline-filling."

On arriving for competition, Minichiello couldn't help but take an early look.

"While Jess was in the call room a few minutes before the hurdles I snuck out and went into the stadium," he says. "For the first session of the heptathlon there is usually one man and his dog there.

"I saw it was full. I went back straight in and said: 'There's 80,000 of your mates turned up to watch you.' I couldn't keep that from her. Prepared is pre-armed."

It worked. Ennis-Hill's time of 12.54 seconds was the fastest ever in a heptathlon. Incredibly, it would have won individual 100m hurdles gold at four of the previous five Olympics.

"The noise the crowd made when Jess was on the start line, then what happened 12.54 seconds later, that is what won her the gold medal," Minichiello says now. "After that everybody else thinks, who's getting silver?"

Naturally deferential, Ennis-Hill baulks at any suggestion she had it won so early - especially with a nagging doubt about the long jump hanging over her. But, as she does several times during an hour-long conversation looking back on a career-defining victory, she admits that during those two days she often felt like a one-off version of herself.

"During the warm-up I felt different," she says. "My legs were just turning over really quickly and it made me feel like oh, is there something wrong? Obviously instead it was a good different because I was ready to run the fastest time of my life."

She soon showed that strength again. Having flown out of the blocks in the hurdles, she consolidated her position at the top of the standings with a jump of 1.86m in the next event, the high jump.

A throw of 14.28m in the shot put saw her slip to second overall heading into the fourth and final event of day one, the 200m.

Ennis-Hill's winning points total was the best at the Olympics in 20 years

The next scene comes just after 9pm - it is now 15 hours since her 6am alarm call. The Olympic Stadium is under floodlights. The best seat in the house belongs to Laviai Nielsen, a 16-year-old Londoner who, as a volunteer kit carrier and sometime athlete, is walking into the stadium carrying the future Olympic champion's tracksuit.

The experience will affect Nielsen so profoundly that she will immediately knuckle down in the sport to such an extent that five years later, she will win a World Championship silver medal in the same stadium.

Back in 2012 she was transfixed by Ennis-Hill's focus. The smiles on the start line for the 100m hurdles at 10am were gone. "As we walked out, the noise and the number of camera flashes was just incredible but I remember Jess just totally blocked it out," Nielsen says. "It was like she couldn't hear any of it."

For the second time that day, Ennis-Hill ran faster than she had ever done before - and ever would again. A 200m personal best of 22.83 seconds (which remained intact until her retirement) earned her an overnight lead of 184 points - but there would be no peace just yet.

"I came away from day one thinking this is the best day I could ever have wished for at a home Olympics," she remembers. "But also 'oh my gosh, everyone is looking at me thinking she has got it in the bag'.

"By the time I'd eaten, showered and got ready for bed it was past midnight and I knew I had to be up at five the next morning."

Ennis-Hill never usually struggled to sleep between the two days of a heptathlon. But despite her lead, she tossed and turned. Irrational fears about whether her alarm would go off - "I must have set at least three" - were part of the problem. Also concerning her was the first event of day two. The long jump.

To understand the extent of those fears, we need to rewind a little.

Minichiello began to coach Ennis-Hill when she was 13 years old

Just weeks before London 2012, Ennis-Hill remembers calling fiance Andy Hill in floods of tears from a preparation camp in Portugal. Training for the heptathlon is a constant juggling act, with athletes rarely having the time to concentrate too heavily on one event. In Portugal they scheduled four long jump sessions. "It was unprecedented," Minichiello remembers. "But we had serious problems."

"I was having the worst time with the long jump," Ennis-Hill says. "I was feeling like that was going to be the event to make everything unravel. My rhythm was all wrong. It knocked my confidence and I was just getting really frustrated.

"We had to have a crisis meeting. I think Tony organised it without me at first. But I got wind of it and joined in. It was just really tense. I remember going back to my room and ringing Andy and saying 'I've ruined it all, it's all going to fall apart in this event' and him just trying to make me see sense of it.

"It was a massive, massive, massive worry for me going into the Olympics. If I'd only been able to jump five metres there, London 2012 would have been a very different story."

A five-metre jump was exactly how Ennis-Hill's heptathlon story resumed on day two.

Was a jump of 5.95m in the first round proof she was about to mentally unravel? No. It was a brain fade of a different kind. Up in the stands, Minichiello worked out what had gone wrong.

"She took 19 strides rather than 17," Minichiello says. "It was a technique we hadn't used for two years. Bricey [Ennis-Hill's biomechanist Paul Brice] asked me what I was going to say to her and I said, 'I don't know, but I'll work it out by the time I get to the bottom of the stairs'.

"In the end, I didn't even mention the fact that she was using the old technique, I just told her to move her starting mark back two feet."

Hearing Ennis-Hill speak about Super Saturday eight years on, there is a constant sense of how London 2012 was unique. Athletically, it was indeed a one-off. Her final tally of 6,955 points remained her personal best until her retirement.

But emotionally she also regularly had moments where she became a woman she didn't quite recognise. The long jump was one such moment.

Minichiello's adjustment paid off. A jump of 6.40m in the second round was followed by 6.48m in the third. Cue some wild celebrations.

"Jess is not a double fist pump person," Minichiello says. "Her typical celebration in the high jump for example is to jump up and down like a pogo stick and clap her hands. She's not an aggressive-type celebrator. What you saw after the long jump was someone who had overcome adversity."

"I was different," Ennis-Hill says. "I was punching the air, I was so happy because I knew that was such a turning point.

"There was so much riding on London. It was just on such a big scale - not even just in the sporting world but in a huge global sense. I had never felt anything like that before. It really brought out emotions in me that normally I would have been able to keep a hold of, bottle up, then cry and celebrate behind closed doors. That's how I'd always done it. But in those two days of competition in London there was no way of controlling that. It just meant so much."

It was the javelin that cost Ennis-Hill at the 2011 Worlds

Minichiello's own out-of-character celebration came after the penultimate event - the javelin.

The anxiety this time dated back 12 months to the 2011 World Championships in South Korea. Despite outperforming Tatyana Chernova in five of the seven events in Daegu, Ennis-Hill managed a throw of just 39.95m to her Russian rival's 52.95m in the javelin. That 13-metre gap ruined any chance of winning gold (although Ennis-Hill was later upgraded from silver when Chernova failed a drugs test). Minichiello said in interviews at the time that her javelin capitulation had left him "stunned".

London witnessed a stunning turnaround. Ennis-Hill outperformed Chernova - throwing 47.49m to the Russian's 46.29m. That previous year's painful 13-metre gap became a joyous 13-second cushion over her nearest rival, Lithuania's Austra Skujyte, before the final event, the 800m (in the heptathlon, points are converted into seconds for the 800m).

"Toni was obviously a bit unsure as to whether the javelin was going to go to plan," Ennis-Hill says. "He doesn't normally show the emotion he showed. That was the point where we kind of knew that I would have to do something pretty terrible to mess it up going into the 800m."

If the attitude on day one from Ennis-Hill's support team was one of restraint, now, with the gold medal all but hers, they couldn't be contained.

"I met up with Mick Hill [javelin coach] and Mick can't hold back his emotions," she says. "He was absolutely buzzing and was like, 'you've done it, get that gold round your neck, you've done it'. I knew I hadn't but it was just a really strange environment. Even Toni was upbeat and positive."

With a near seven-hour break between the conclusion of the javelin and the 800m, all but one of her fellow competitors headed back to their apartments in the Olympic village. Having spent years religiously keeping away from the stadium, now she couldn't bear to leave.

And so, before the gold medal moment that cemented her place in the limelight forever, Ennis-Hill wiled away the afternoon in a windowless room in the bowels of the Olympic stadium, watching dressage on mute.

"There was very little in the multi-events relaxation room: just a few mats and foam rollers and things," Minichiello remembers. "To be honest, I was thinking I could cop a snooze for a few hours as I hadn't slept well at all.

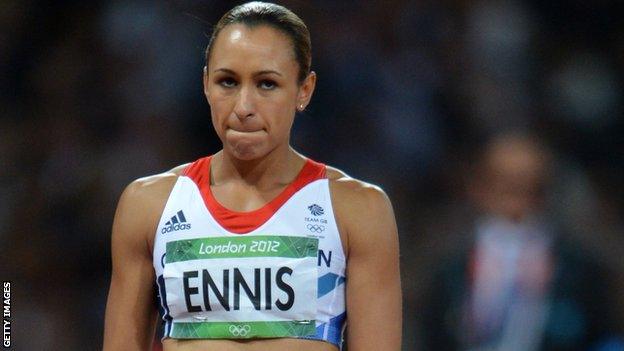

Moments before the 800m, with victory all but secured, Ennis-Hill was still feeling the nerves

"But Jess wouldn't leave me alone. She was bugging me asking me what lead she had and how many seconds it was."

As she knew perfectly, the margin [13 seconds] was massive. The only threat to her gold-medal coronation was injury. A danger she understood only too well.

Four years previously Ennis-Hill had been preparing to make her Olympic debut at the Beijing Games in 2008. Having finished fourth at the 2007 World Championships in Japan she would have headed back to the Far East as a medal contender. A stress fracture in her foot meant she missed out.

In the BBC footage of the call room before the 800m, two things stand out. First is the size difference between the giant Chernova and the diminutive Ennis-Hill. The second is how calm Ennis-Hill appears. In reality, she was anything but.

"I was just so nervous," she says. "It makes me feel anxious and nervous about it even thinking about it now. That feeling will never leave me. It was the best - but worst - feeling ever.

"In the call room before the race there was some eye contact, but you can see everyone is just consumed by fear. Some athletes were being quite intense, slapping their legs and psyching themselves up. Others were just sat in the corner. With everyone though there was that common feeling of just nervousness, and fatigue, because at that stage you are exhausted from two days of competition. You just want it to be over."

Two minutes, eight seconds later it was. Ennis-Hill led the race early before appearing to run out of steam. The gold medal was never in danger, but she desperately wanted her crowning moment.

Twelve months earlier, the back pages of the national newspapers all featured the same image of her defeat at the World Championships. The imposing Chernova crossing the line arms aloft, with Ennis-Hill a few metres behind, diminutive, deflated and defeated.

"I was like 'I am not having that feeling again," she says. "'I am not having it at the Olympics in London.' I really wanted to prove a point and beat her. No doubt Steve Cram would be pulling his hair out in terms of my 800m running from a tactical perspective. In the last 200m I just felt like I had been through that pain before so many times in training. This was my one opportunity to have that moment across the line. I had to do it."

Ennis-Hill found the second wind she needed. Coming into the home straight it was clear that her career-defining moment was going to reach the perfect climax. By its nature the heptathlon - combining seven events over two days - often doesn't finish with the overall victor crossing the line first. In London, the stars aligned and Ennis-Hill did just that.

Relief in victory. Ennis-Hill would go on to win heptathlon silver at the 2016 Olympics - two years after having her first child

In the immediate aftermath of her victory, the pictures show her carrying a Union Jack with the words "Jessica Ennis, Olympic champion" on it.

Her soft tissue therapist coach Derry Suter had had it pre-made. Such an act of presumptuousness didn't sit right with Ennis-Hill or Minichiello. Their reactions though, typically, contrast.

Ennis-Hill first: "When he gave it to me, I was like, 'Derry, you have had that made up'. If I knew he was doing that behind the scenes I would have been like, 'no, no, you're jinxing me'."

Minichiello: "I'd have burnt it if I'd known."

Suter's act can be seen as a metaphor for the attitude of the nation at large.

Ennis-Hill stayed away from the Olympic Stadium in the years building up to 2012 but she couldn't stay out of the public consciousness. The 'face of the Games' headlines, the 'golden girl' captions, the giant painting of her on the flight path of planes coming into Heathrow - they all combined to create a singular expectation.

Gold.

"I do believe I had a journey and a path through this sport and that was my time," she says now.

"When I was injured in 2008, having the belief that it was part of a process was the one thing that kept me sane. There is a reason for this. I won't see it now but there will be a reason why this has happened.

"Everything came into place in London. Everything aligned for me and for that moment. It was pretty special."

In May 2020, Ennis-Hill's heptathlon triumph was voted Britain's greatest moment in women's sport