Mike Trout: The brilliant $426.5m MLB star most Americans don't know

- Published

- comments

Quick, which player has the largest salary contract in US team sport - in fact, the richest contract in the history of North American team sport?

You might be inclined to say Tom Brady, the charismatic quarterback for the New England Patriots, winner of six Super Bowls. Or basketball luminary LeBron James of the Los Angeles Lakers. Maybe sharp-shooting Stephen Curry of the Golden State Warriors, who has single-handedly revolutionised the game in just a handful of years.

Or perhaps you're familiar enough with US sport to know that the NFL and NBA have salary caps and shorter contract lengths, limiting their players' on-the-books earning potential.

So maybe it's a baseball star, like the demonstrative Bryce Harper, who recently signed a huge free-agent deal with the Philadelphia Phillies. Or Clayton Kershaw, the golden-armed pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Or one of the numerous sluggers on the New York Yankees, Chicago Cubs or World Series-winning Boston Red Sox.

Wrong. Wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong.

Allow me to introduce Mike Trout, starting centrefielder for the Los Angeles Angels who, after signing a 12-year, $426.5m (£340.5m) contract extension in April, tops the North American sport salary list.

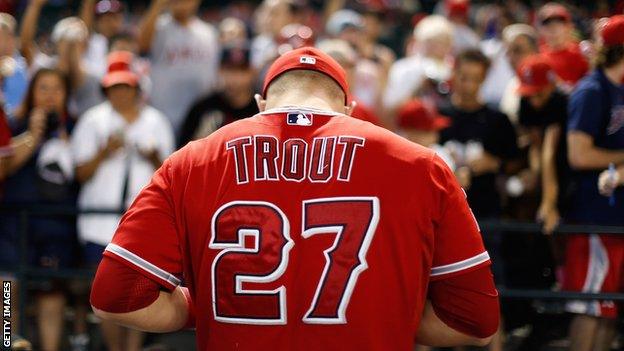

Trout was selected straight out of high school by the Angels in 2009

While some basketball players, like the aforementioned James, make a bit more per year, Trout, 27, will be earning $35m (£27.9m) annual paycheques - guaranteed, unlike other sports - long after 34-year-old 'King James' exits the basketball scene.

What's more, given his performance on the field over his nine-year career, Trout is probably worth every penny - and then some. He is the best player in baseball right now and, arguably, on track to rank among the best players in the 150-year history of the game. His name will be mentioned in the pantheon of baseball legends, alongside the likes of Babe Ruth, Willie Mays and Ty Cobb.

Yet he could walk down an average street in the US unrecognised. He's a baseball great, appearing in his eighth-consecutive All-Star game on Tuesday (Wednesday 00:30 BST), but not a sport celebrity. That seems to be just the way he wants it.

Prior to Trout's interview with BBC Sport, we're told he isn't much of a talker and to be prepared for short answers. It turns out he's happy to chat, he just doesn't sound like a typical big-ego multimillionaire sports star. He comes across as a small-town high-school kid who just happens to be in the 27-year-old body of a world-class athlete.

That is, essentially, what he is. He walks into the dugout at the Anaheim Angels stadium wearing a warm-up jersey and backward cap, and fidgets slightly as the camera starts rolling.

He talks about how, as a boy, he played baseball, basketball, football, golf - anything with a ball.

Trout grew up in the small southern New Jersey town of Millville - far from the US baseball hotbeds of California, Texas and Florida, where warm weather means baseball can be a year-round activity.

While he had blazing-fast speed as a teenager, he largely flew under the radar for professional scouts. He was selected straight out of high school by the Angels in the 2009 draft with the 25th pick, which means 21 other teams chose someone else. Two teams, Washington and Arizona, let him slip by twice.

That's something Trout remembers.

"A lot of teams shied away because I was an East Coast kid and didn't play a lot," he says. "Other teams passed on me - and I've just tried to prove them wrong ever since day one."

Day one came for Trout on 8 July, 2011 - a mid-season call-up to replace an injured player.

He compares his first Major League appearance to something out of a video game.

"I felt like I was just a kid playing the Xbox or Playstation."

Trout didn't get a hit that night and was eventually sent back to the minor leagues. He would make the Angels team permanently the next year, however - and he never looked back.

He says his game is instinctual - that, unlike some other players, he doesn't think too much about technique or opponents' tendencies.

"For me, less is more," he says. "If I look into stuff too much, that's when I get in trouble. I try to keep it as simple as possible and just go out there and compete."

For Trout, simple seems to work just fine.

Trout's performances have seen him compared with the game's greatest ever players

There are several ways to appreciate exactly how good Mike Trout is.

The first is to list his awards and achievements. He has been the most-valuable player of the All-Star game twice, season MVP of the American League twice and the 2012 AL Rookie of the Year. He has won the Silver Slugger award for best offensive centrefielder six times.

Ted Berg, a USA Today baseball reporter who writes a weekly update on Trout's exploits, has suggested only somewhat jokingly that the MLB should name every applicable award after him.

"There's no greater honour one could bestow upon a baseball player in 2019 than saying he was the guy who played most like Mike Trout in the past week or month or season," he writes., external "Trout is our standard-bearer for transcendent baseball performance, and no player in his right mind could rightfully feel slighted by the comparison."

Another way to appreciate Trout is simply to watch him play.

According to Major League scouts, there are five skills - "tools" - essential to excelling in the game of baseball. Those tools are speed, hitting for power, hitting for consistency, defensive fielding ability and arm strength. Trout is what's called a "five-tool player." He's really good at everything.

When he's at bat, he can hit the ball out of the park - something he's done more than 260 times in his career. When he's not knocking home runs, he's drawing walks or putting the ball in play - and stretching hits into doubles and triples. His career on-base percentage is well over .400, meaning he reaches base in nearly half of his at-bats, a better rate than anyone else in the league over three of the past four years. Once he's there, he's a disruptive runner, with nearly 200 career steals.

On defence, he plays a challenging position - centre field - where he chases down fly balls, making acrobatic dives and catches at the wall and gunning down runners trying to push for an extra base.

Trout is, quite simply, an exciting player to watch at any moment he's on the field.

"He's just very talented offensively from a speed and a power standpoint," says Brad Ausmus, the Angels manager who had an 18-year career as a catcher in the league. "He's a once-in-a-generation player. I don't know how else to describe it."

There is another way to describe it. To fully understand what sets Trout apart, one has to delve deep into the esoteric world of baseball statistics - a domain where numbers like home runs, batting average, steals and even on-base percentage are mere building blocks in much more sophisticated calculations.

Statistics are the lingua franca of baseball devotees in a way that's unlike any other sport.

"The baseball season is long, and while you watch the best player, you might not get a sense of how good he is from that one game," says Jay Jaffe, a sports journalist and baseball statistician. "The true students of the game use statistics to get a better perspective on what they're seeing and where the players fit into the grand scheme of things."

One of the trendy current ways of measuring a player's skill is through a number called "wins above replacement", or WAR. It's a calculation of someone's contribution to a team compared to what would be made by a faceless, slightly-below-average replacement player. It's measured in the number of additional team wins the named player could account for over the course of a 162-game season and factors in batting, base-running and defensive capabilities - in effect, how all the baseball tools interact and produce results on the field. The number adjusts for a player's home ballpark, fielding position, and differences in competition and baseball eras.

Mike Trout is the god of WAR, a hero to baseball stat-heads everywhere.

Someone with a season WAR total of around five is playing at an all-star level. Trout has averaged a WAR of 9.1 over his seven full seasons and led the league in four of them. He has a career total of 69.7, which ties him for second among all active players - behind only team-mate Albert Pujols, who has been playing for a decade longer.

Based on this metric, Trout not only ranks among the greatest players in the game right now, but the greatest of all time.

In his book The Cooperstown Casebook, Jaffe aggregates these WAR ratings into a figure he calls the Jaffe WAR score system (JAWS, for short), which takes the average of a player's total WAR and sum of his WAR over the best seven years of his career. It is, he explains, a way to measure Hall of Fame calibre players who are consistently remarkable over a long career or electric for shorter periods of time.

Trout is already the latter - and he's on his way to being the former.

The average JAWS score for a Hall of Fame centrefielder is 57.8. Trout's 69.7 is already the sixth-highest score, despite his seven-year peak score effectively being the entirety of his playing career. All the players above him, like Willie Mays, Ty Cobb and Mickey Mantle, are baseball legends.

"This is unprecedented," Jaffe says. "For Mike Trout to build as strong a Hall of Fame case as he has in this short a time is remarkable."

He adds that a credible conversation about the best overall player in the history of baseball begins and ends with only four men: Ruth, Mays, Barry Bonds and Trout.

According to a survey, only half of American sports fans know who Trout is

So if Mike Trout is a baseball legend walking among mere mortal Americans, why do so few people know who he is?

According to the market research firm Q Scores, 22% of the US general public is familiar with Trout. Basketball star Curry and NFL quarterback Drew Brees, on the other hand, are over 50%.

Among sport fans, Trout reaches the 50% mark. But Tom Brady and LeBron James, for instance, have near universal recognition.

Part of the problem for Trout is that baseball, despite being the self-proclaimed 'American pastime', just doesn't produce identifiable stars the way American football and basketball do. The league is large, the games are numerous, and due to regional cable sports networks, the teams and their players have smaller media footprints.

The situation is compounded for Trout because he plays on a California team, most of whose games don't start until late in the evening for East Coast viewers. And the Angels, while located in the Los Angeles metropolitan area, have always been the little brother to the Los Angeles Dodgers - the Manchester City to their Manchester United.

The franchise's identity issues are reflected in the revolving list of names the Angels have gone by in their 58-year history - the Los Angeles Angels, the California Angels, the Anaheim Angels (for the actual town in which they play) and finally the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim (which resulted in the team being sued by city governments in both Los Angeles and Anaheim).

By whatever name, the team has only won a single championship, in 2002, and has only made the play-offs once in Trout's career, a 2014 first-round sweep at the hands of the Kansas City Royals. Despite Trout's contributions, the team has posted three consecutive losing seasons and is currently in fourth place in its five-team division.

Post-season games - and, particularly, the World Series - are where baseball players can begin to command the nation's attention. It's a stage Trout, whether because of bad luck or bad decisions by the Angels management, simply hasn't had the opportunity to enjoy.

"A lot of people say 'Mike hasn't been to the play-offs, Mike needs to do this or do that'," Trout says. "Obviously, I've got 12 more years to prove myself."

A conversation about why Mike Trout isn't a sport superstar has to include a discussion of Mike Trout himself.

He chose, after all, to sign his 12-year contract extension with the Angels without ever testing the free-agent market, where he certainly would have been courted by big-name East Coast teams like the Yankees - his childhood favourite.

Last July, in the midst of the 2018 All-Star game, MLB commissioner Rob Manfred, the top executive for the sport, directly questioned Trout's dedication to building his "brand".

"Mike has made decisions on what he wants to do, doesn't want to do, how he wants to spend his free time or not spend his free time," Manfred told an interviewer. "I think we could help him make his brand very big, but he has to make a decision to engage."

The critique clearly gets under Trout's skin.

"I'm here to do one thing, and that's play," he tells me when I ask about the Manfred jab. "I think I do a great job of doing things I need to be doing, but I can't burn myself out. I've got to be able to go out there and perform and be myself."

For Trout, that means keeping a low profile. While other players show off for the fans during outdoor pre-game batting practice, Trout usually retreats to an indoor cage to work on his swing. A popular feature of the All-Star break is the Home Run Derby, a glitzy, informal chance for power hitters to strut their stuff. Trout has given it a pass despite, he says, being asked by baseball "every year".

Trout met his wife, Jessica Cox, in high school, and during baseball's four-month off-season, they return home to Millville. Trout says he spends most of his time there hanging out with friends and family, playing golf and hunting.

"Trout has chosen to remain a bit of a cypher," says sports reporter Jaffe. "He's not necessarily here to be the number-one ambassador for the sport. He's here to play ball, and that's it."

"They treat me right," says Trout of his relationship with the Angels

If Trout doesn't have the national following his performance might merit, he has earned the undying love of Angels fans in southern California - and not just because of his skill.

"A lot of times, especially in today's sports, you see guys taking the big money somewhere else, and maybe not so much on the West Coast," says Angels fan Matt Evans. "He's honestly the greatest player in the game, he's super loyal, he's a leader and he's constantly getting better."

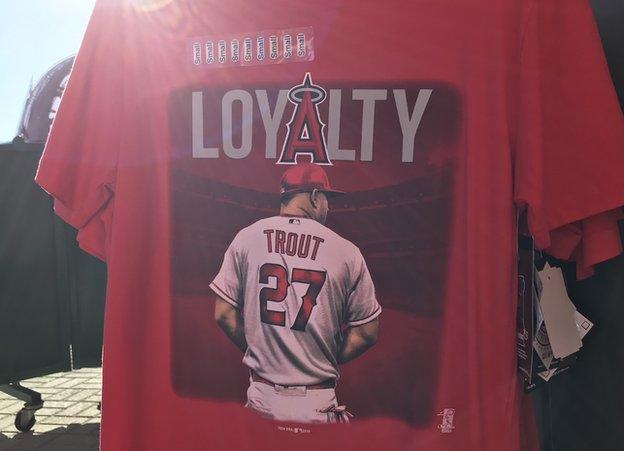

'Loyal' is a word that comes up time and time again among the crowd of thousands, many in Trout jerseys, milling around the Angels ballpark - affectionately called 'the Big A' - before a game against Seattle on a balmy California evening in June.

A T-shirt for sale in the stadium's souvenir shop features a photograph of the player, his back to the camera, with one word written above: Loyalty.

"When Trout announced he was staying, we were all cheering at home," says Jocyln Marin, who made the one-hour trip from Apple Valley with her family to see the Angels play. "It's nice to have a player of his calibre stay here and not just leave once he gets bigger."

I asked Trout about his decision to stick with the Angels. Loyalty, for him, is a two-way street.

"I've built so many friendships here and met a lot of great people," he said. "They treat me right."

Despite Trout's transcendent performance so far, there is some measure of risk in the Angels' decision to sign him to such a record-breaking contract. While he's been healthy for most of his playing days, there is always the chance of a career-threatening injury.

Even without injury, the ravages of time - or simple slumps - can take a toll on a player's game. Mookie Betts of the Red Sox was last year's hot player, edging out Trout for the league's MVP award. Essays were penned, external on his hitting prowess and season-leading WAR total.

This season, Betts' numbers have crashed back down to earth.

Meanwhile, Trout just keeps plugging along, content to stay out of the limelight and play the game as well as he can for as long as he can.

"At the end of my career, I want to be the guy that people say, he was one of the best, if not the best," Trout says. "That's my mentality. I want to go out there and say that I left it all out on the field."

Jaffe, as a baseball historian and fan, is more direct.

He says he thinks Trout is somebody that a large percentage of the population will regret being slow to wake up to. "We're seeing something truly special, and I hope the appreciation for that comes with time."