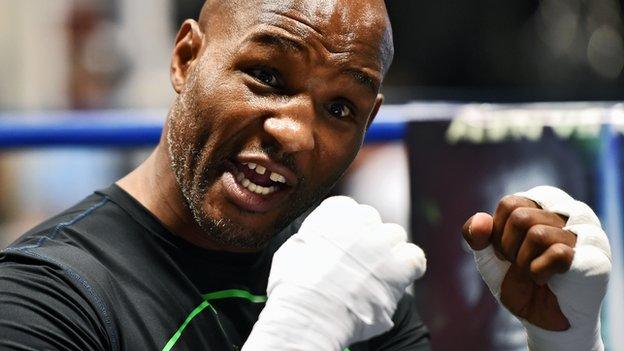

Bernard Hopkins: Boxing's oldest world champ still rumbling at 49

- Published

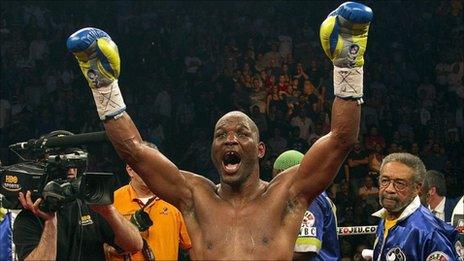

Bernard Hopkins, boxing's oldest ever world champion

This is a slightly updated version of an interview that was first published on the BBC Sport website in April of this year.

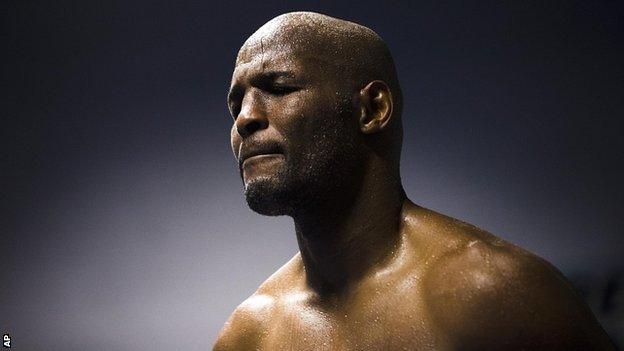

Halfway through an hour-long conversation with Bernard Hopkins and boxing's great philosopher is preaching his own branch of metaphysics: life, the universe and everything. Or, in short, how did he get here?

And I find myself thinking the same - how did he get here? - but on a far more basic level. Moments earlier we were discussing what he had for breakfast - hash browns and pancakes, sparkling water and cranberry juice. But that's only part of his secret.

"Billions of people on this earth, so why me?" says the 49-year-old American, the oldest world champion in the history of boxing.

"Why me, who got stabbed three times on the streets of Philadelphia? Why me, who beat up everybody and took everything they had? Why me, who was incarcerated for five years? Why me, who lost my first pro fight? WHY ME?!

"There are so many black youths dying every day like flies on the streets of America. I was just like them. But now I understand. Every now and again, history brings along a person who stands out. I believe in the unseen and that some are chosen and some are not. If I sound crazy, then tell me why I've been around this long. Luck? Luck doesn't strike that many times in anybody's life."

When Hopkins starts steaming like this, he sounds unnervingly like Samuel L Jackson in Pulp Fiction, winding himself up for an execution. But he has earned the right to thunder from his pulpit.

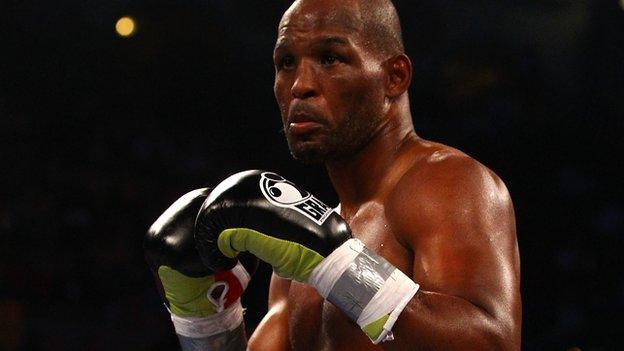

Hopkins won his first world title in 1995, at the age of 30, before defending his middleweight crown 20 times. On Saturday, he faces Russia's Sergey Kovalev in a light-heavyweight unification match in Atlantic City. Should Hopkins beat Kovalev, who is 18 years his junior, he would 'only' need to beat WBC champion Adonis Stevenson, external next year to become undisputed champion at 50.

But to truly appreciate Hopkins' achievements and what his achievements can teach those less blessed than him, you have to know something of where he came from.

Hopkins, one of eight children, grew up on one of Philadelphia's grittiest housing projects. By his early teens he had graduated from petty theft to muggings and was stabbed three times before the age of 14, very nearly becoming just another one of those flies, splattered on the sidewalk.

In 1982, aged only 17 but with a rap sheet as long as his boxing record now reads, Hopkins was sentenced to 18 years in prison. In Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution, Hopkins didn't witness much correcting.

He did, however, witness fellow inmates being raped and murdered. "I saw a guy killed for a lousy pack of cigarettes," says Hopkins. "Something in me snapped."

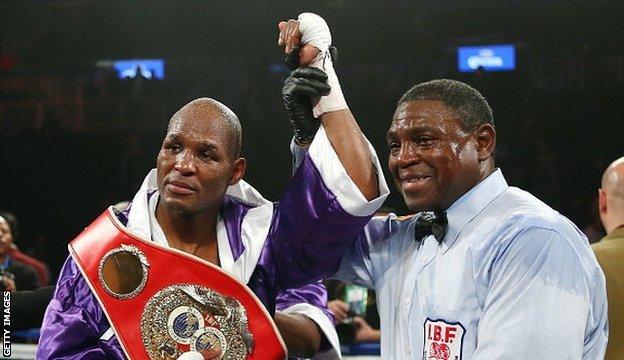

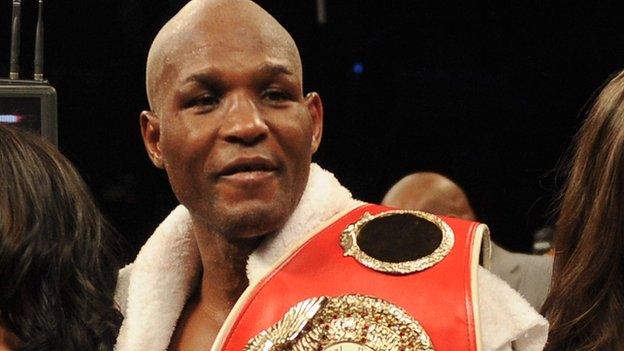

Hopkins beat Tavoris Cloud last March to break his own record for boxing's oldest world champion

Hopkins insists his experiences in prison have informed rather than defined him. Stored in a well in the backyard of his brain - the Well of Eternity? - Hopkins can draw on those experiences whenever his mind and spirit need rejuvenating.

"I'm not motivated by where I've been," says Hopkins. "I'm not stuck back in that box. But if I've got to go back and grab some inspiration and some strength, I can reminisce - briefly - before moving forward again."

Hopkins discovered boxing in prison, around the time of his 21st birthday, before being released in 1988. He lost his first pro fight later that same year, against a light-heavyweight called Clinton Mitchell, and spent 16 months contemplating his next move before resuming his career as a middleweight.

"Some people are afraid to fail," says Hopkins. "But I'm not afraid to fail. I know that if I put in a sincere effort - march, fight, scream, like my ancestors did when they were paving the way for me - I'll get through it."

Hopkins spent the first half of the 1990s as "the third man in the house", behind James Toney and Roy Jones Jr. The lavishly gifted Jones beat Hopkins in a world title encounter in 1993,, external before Hopkins won the IBF middleweight crown almost two years later, courtesy of a stoppage of Ecuador's Segundo Mercado.

In those early years, Hopkins was known as a knockout artist. But as the world title defences mounted up he garnered a reputation as a master tactician.

"In life, some people are playing chequers and some people are playing chess," says Hopkins. "Chess is a game where you have to use the right pieces and the right moves depending on the set-up, thinking four or five moves ahead.

"And only certain fighters, who I'm struggling to count on the fingers of one hand, already know what they're going to do four or five punches ahead.

"The jab is the pawn, but you've also got your bishop, your rook, your knight and, of course, your king and your queen. To survive in the world of boxing, in the world of corporate America or on the streets, it's all about strategy."

When Hopkins entered his late-30s, he began to pare down his strategy even further. Jones recently suggested his old rival, who won their rematch in 2010,, external had two moves left in his armoury, his overhand right and his headbutt. He was only half-joking.

But this has always been part of Hopkins' glory. Like your dad, he gets jobs done with the old tools hanging in his shed. Old tools lovingly maintained, so that they are every bit as effective as the tools any of these young kids are wielding.

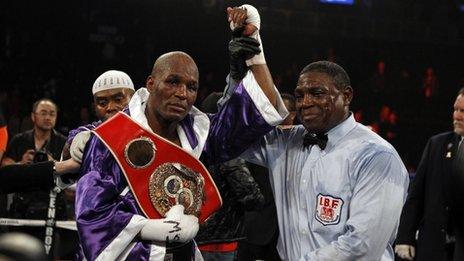

The old tools he used to dismantle rugged Canadian Jean Pascal,, external a man 18 years his junior, in 2011 and become the oldest boxer to win a world title. The old tools he used to dismantle Tavoris Cloud, a man 17 years younger, last March and break his previous record.

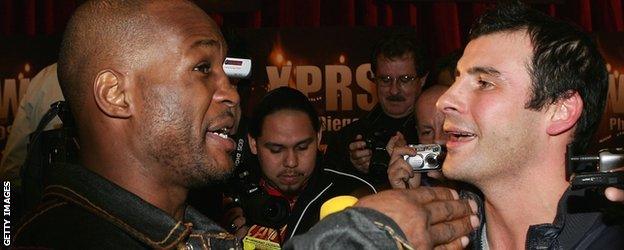

The outspoken Hopkins taunted Calzaghe in 2007 but was beaten by the Welsh legend the following year

But throughout his career, Hopkins has been a unifier and a divider. So while many boxing fans find his feats inspiring, many others find him boring between the ropes and boorish beyond them.

At a press conference to promote his fight with Felix Trinidad in 2001, Hopkins sparked a mini-riot, external - and world-wide interest in the upcoming contest - by throwing the Puerto Rican flag to the floor.

In 2007, Hopkins caused uproar when he told Welsh legend Joe Calzaghe: "I would never let a white boy beat me." Calzaghe didn't mind, outpointing Hopkins, external and making a mint in Las Vegas a few months later.

The first time I interviewed Hopkins was before Ricky Hatton's fight against Floyd Mayweather, a couple of days before his altercation with Calzaghe. When Hopkins strolled into the press room at the MGM Grand unaccompanied, I thought I had him to myself.

Twenty minutes later, Hopkins was still replying to my opening question and we were surrounded by a scrum of journalists and cameramen, 30 or 40 strong. Some exclusive.

So you might expect Hopkins, a man who can riff endlessly on pretty much any subject, to be an evangelist for boxing - a sport that gave him an alternative to stabbings and beatings, a sport that gave him glory and riches. But in Hopkins's mind, boxing is merely an extension of prison - out of sight and full of spite, sport's punishment block.

"I would never want anybody I care about to box," says Hopkins, who is a passionate advocate for an ongoing American study into head injuries in combat sports. "In fact, I would tell my worst enemy's kids not to box.

"I don't believe that the body, especially the head, was made to be hit. So if any of your kids or grandkids want to box, distract and discourage them early.

"You want to teach kids about the dangers of violence on the streets? Take them to the morgue, let them see the victims of gun crime. You want a kid not to smoke crack? Show him a crack-head. Your kid wants to box? Start off by showing him Muhammad Ali.", external

Having shown your kid Ali, who has been fighting boxing-induced Parkinson's disease for more than 30 years, you might want to show him or her Roy Jones and James Toney.

Jones, a candidate for the greatest fighter of the modern era, is squeezing out his last against obscure opponents for questionable titles in eastern Europe. Toney, a three-weight world champion, was last seen blundering around a ring in London. Overweight, shorn of his reactions, incapable of lucid speech, no more to give but still trying to give it.

Both Jones and Toney are 45, four years younger than Hopkins. But Hopkins feels somehow responsible for their latter-day travails.

"It saddens me because they were the kings of another era and they're not representing themselves in a real light," says Hopkins.

"But I'm partly to blame for their delusion, because they think they can do what I'm doing. I'm accidentally to blame for a lot of fighters in their late-30s or 40s thinking they can have another run at it. Or, even worse, never getting out in the first place."

Hopkins and US Senator John McCain are backing a major study into head injuries in combat sports

Ask Hopkins the secret of his longevity and he will claim there is no secret. Early to bed, early to rise, eat good things, avoid bad things, do plenty of exercise. But it is his longevity that he is most proud of, more than any victories or titles.

Hopkins is four years older than George Foreman was when he regained a portion of the world heavyweight crown in 1994;, external Hopkins is only three years younger than Phil Taylor, who won the PDC World Darts Championship last year at the age of 52. But while Hopkins gets punched for a living, Taylor's game is rather more sedentary.

"When I beat Felix Trinidad in 2001, I was 35," says Hopkins, who eschews the high-octane lifestyle of fellow American legend Mayweather, external in favour of a quiet family life in the small town of Hockessin, Delaware, with his wife Jeanette and their three children.

"People were already calling me old back then. My mom wanted me to stop when I was 40. But nine years later, the fans have got the chance to see some of the most historic achievements that any athlete in any sport has ever created. Now I'm looking forward to number 50.

"I'm going to play it out until the song is over, like a record. I will know when to go - when I don't feel I can do it any more on a respectable level.

"I'm not as talented as the great Roy Jones. But I'm different - I'm 'The Alien'. From day one, my journey was written the way it's been played out. So it won't be a sad ending for me, I'll bet you that."

An hour is up but Hopkins tells me he will carry on fielding enquiries, if I wish to carry on making them. However, I notice an email in my inbox, from his exasperated publicist: "PLEASE, I AM GOING TO PULL IT! DO NOT ASK ANY MORE QUESTIONS!" To be fair, I only asked five. And I wasn't expecting life, the universe and everything.

- Published6 November 2014

- Published5 February 2014

- Published27 October 2013

- Published10 March 2013

- Published22 May 2011