Carl Frampton: Barry McGuigan's gamble pays off in Belfast

- Published

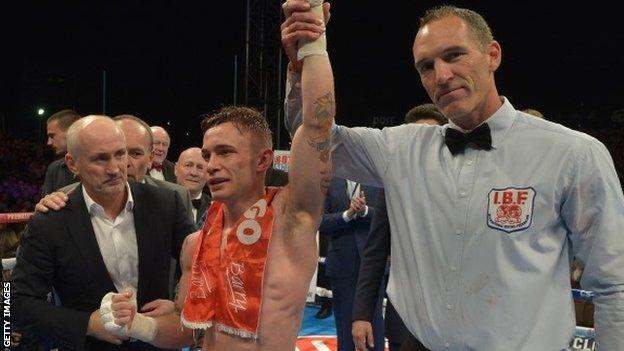

Frampton (centre) followed in McGuigan's (left) footsteps by becoming world champion

Special night in Belfast. Special fighter. One wistful punter summed it up perfectly while scanning the foaming arena: "It's just like the Barry McGuigan days again."

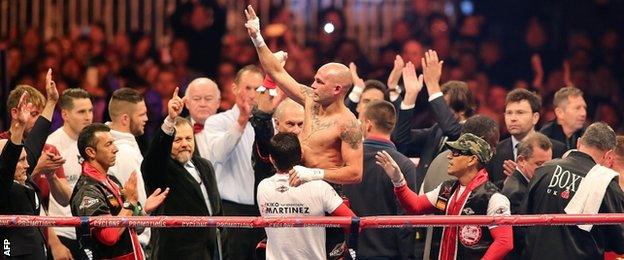

Having beaten, bored and bent Kiko Martinez for 12 rounds in front of 16,000 euphoric fans in Belfast's Titanic Quarter, perhaps Carl Frampton can better relate to his forefathers from Tiger's Bay - those workers who flocked to the old shipyard in its glory days, to bash great boats into shape.

We knew Martinez was game but after an almost insanely brave performance in attempting to defend his IBF super-bantamweight title, Frampton should demand the Spaniard's head be checked for steel plates and iron rivets. By the end of it Frampton's left hand was spent, like a hammer all splintered and bent.

Neilly commentary

At the post-fight media conference, Frampton's own face was a mass of lumps of bruises. Asked what he said to Martinez after ripping his title away on a unanimous decision, Frampton replied: "I told him I respect him like no other boxer I've fought - and that I hope I never see him again."

McGuigan, Frampton's manager and promoter and a relentless pressure fighter himself, appreciated Martinez's efforts. But he appreciated Frampton's more. Indeed, post-fight, he looked relieved rather than elated.

"He's twice the fighter I was," said former featherweight world champion McGuigan, after Frampton was awarded a one-sided unanimous decision. "He could end up being the greatest Irish fighter ever."

The greatest Irish fighter ever could well be McGuigan, who dethroned the legendary Eusebio Pedroza in front of a television audience of 20 million in 1985 and brought some semblance of unity to a war-torn country.

In the intervening years, boxing and Northern Ireland have changed. The former has parted company with terrestrial television and the latter is almost at peace again. As such, Frampton is yomping across a very different landscape.

Frampton's journey | |

|---|---|

Born | 21 February 1987, Belfast, Northern Ireland |

Family | Lives with wife Christine and three-year-old daughter Carla in Lisburn |

Boxing background | Started boxing at Midland ABC, Tiger's Bay before moving to Holy Family ABC in New Lodge as a professional |

Connections | Managed by Barry McGuigan, trained by Barry's son Shane in London |

Amateur record | 125 fights, 114 wins, 11 defeats; two-weight Irish champion; European silver medal 2007; 12 international medals |

Pro record | 19 fights (13 KOs), 19 wins |

Pro honours | World, European & Commonwealth super-bantamweight champion |

McGuigan took huge risks to deliver his charge a world title shot - building a temporary stadium at great cost and forking out a significant sum of money to bring Martinez to Northern Ireland.

Carl Frampton talks about beating Kiko Martinez to win the IBF super-bantamweight championship.

But McGuigan was banking on two key things remaining the same from his heyday: the country's ability to produce and nurture world-class boxing talent and the deep love the people of Belfast have for the fight game.

Having offered them a new gloved hero and a suitable cathedral for him to perform in, the Belfast faithful, of all denominations, came to venerate in droves. "When you've got a kid going into bat for you like Frampton," said McGuigan, "you know you've got a really good chance of succeeding."

Frampton is certainly a more rounded boxer than McGuigan. While his mentor was a swarming, come-forward fighter, Frampton can box going forwards or backwards. He can also box on the outside, up close, vary his shots, plant his feet and mix it. Plus, he has a solid set of whiskers, always handy in his trade.

That Frampton is such an accomplished boxer after only 19 fights as a professional is the source of a double-dose of pride for McGuigan, because it is his youngest son Shane, only 24, who is Frampton's principal trainer.

Nevertheless, one big win can soon be forgotten and so greatness must wait. The good news is Frampton has plenty to test his potential greatness against.

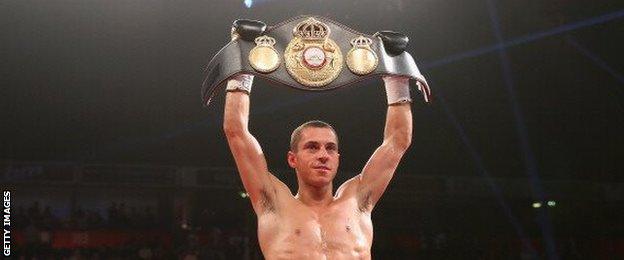

Top of the 27-year-old's wish list is Bury's unbeaten WBA title-holder Scott Quigg, who defends against Belgium's Stephane Jamoye in Manchester next Saturday and whom Frampton called out immediately after his victory over Martinez.

Quigg will be making the fourth defence of his title against Jamoye after a second-round stoppage of Tshifhiwa Munyai in April

Frampton and Quigg have been circling each other for years and now would seem like the perfect time to settle things. If only things were that simple. While McGuigan insisted Quigg would have to fight his man in Belfast, he also acknowledged there isn't a big enough arena in Belfast to put the fight in.

Factor in the strained relationship between Quigg's promoter Eddie Hearn and Frampton - they parted company last May - and negotiations are sure to be both tedious and tortuous, even by boxing's labyrinthine standards.

Another possible unification match would be against Mexico's unbeaten WBC champion Leo Santa Cruz, who defends his title on the undercard of Floyd Mayweather-Marcos Maidana II in Las Vegas next Saturday. Santa Cruz is a tough, all-action customer but Frampton believes he's also one-dimensional.

Unsurprisingly, one man who was glossed over in Saturday's post-fight conversations was WBO and WBA 'super' champion Guillermo Rigondeaux. Because while the Cuban is widely regarded to be the most gifted boxer in the 122lb division, unfortunately for him, he's too gifted for his own good.

"Don't get me wrong, he's fabulous," said McGuigan. "But he's awkward, negative, not nice to fight, impossible to look good against, brings no support, no money, no television and makes no financial sense."

I think it is safe to say that Frampton will not be fighting Rigondeaux any time soon.

"Frampton should demand Martinez's head be checked for steel plates and iron rivets. By the end of it Frampton's left hand was spent, like a hammer all splintered and bent."

Sitting quietly at the back of the room while future Frampton opponents were being discussed was IBF supervisor Lindsey Tucker. Tucker might have been irritated or amused, because he had already told BBC Sport that Frampton is contracted to fight American Chris Avalos (24-2), the mandatory challenger, next.

This is because Martinez was given special dispensation to defend against Frampton, meaning Avalos, ranked number one by the IBF, had to step aside. Tucker said McGuigan should expect a letter on Monday, explaining that the two teams have 30 days to negotiate a deal, or the fight will go to purse bids.

Intriguingly, Avalos recently signed a promotional deal with Hearn, moving Frampton to remark: "He's like an old girlfriend who won't go away."

If Frampton's hand is broken, then we won't see him in action until next year anyway, by which time Avalos might have chosen a different route - he hasn't fought since May and is also mandatory challenger for Rigondeaux's WBO belt.

But it isn't only his hand that Frampton needs to rest - it is his shoulders, too. For while Frampton might appear calm and collected, the pressure he's been under these past few months would have crushed a weaker individual.

His mentor gambled big on him, his people expected. He expected great things of himself, he ultimately delivered. War is over, time to get some peace.

Frampton floored Martinez with a short, chopping right towards the end of the fifth round

- Published7 September 2014

- Published7 September 2014

- Published3 September 2014

- Published11 June 2018