Mike Towell death: Why thought of abolishing boxing should be resisted

- Published

- comments

Mike Towell celebrates his win over Danny Little with his management team in 2015

You might think the fact that Mike Towell's defining battle took place on an operating table rather than in a ring would cause even boxing's most ardent supporters to question its legitimacy as a sport, perhaps even its existence.

But the day after the Scottish fighter died, having sustained severe bleeding and swelling to his brain in a British title eliminator on Thursday, boxing gyms would have been full across the country. "Tragic news about Mike Towell," they would have said, before savagely assaulting a heavy bag.

On Saturday, professional boxing shows took place in Buxton, Manchester, Stoke, London and the former Yorkshire pit village of Denaby Main. In Glasgow, where Towell's final prize fight took place, 22 men climbed between the ropes at the Bellahouston Leisure Centre. Some won, some lost, some had their senses scrambled. But none was there against his will.

Abolitionists argue that such people should be saved from themselves. And if you were to build a utopia, boxing would surely not be a part of it. But anyone who reads the newspapers or watches the news will know that utopia is not imminent. And, anyway, how utopian is restricting a person's choice?

I didn't know Towell but I have met many men like him. The typical boxer is diffident, far removed from the lazy stereotype of the snarling bully. But the typical boxer - or at least the typical boxer who has tasted success in the ring - will also speak of an addictive, sometimes pathological, need to fight.

Mike Towell was knocked down in the first and fifth rounds of the fight against Dale Evans

This need isn't necessarily financial. Carl Froch, one of the most determined boxers Britain has ever produced, studied sports science at Loughborough University. Welshman Nathan Cleverly, who became a two-time world champion on Saturday, has a degree in maths.

They were never the desperate street urchins or would-be criminals of so much boxing fiction. Had they so desired, Froch could have been a physio and Cleverly a high-school teacher.

However, it is true that boxing has diverted many aimless souls down a path towards self-improvement and dignity. The best grassroots boxing trainers don't just know their way around a ring, they are social workers, fathers and mothers.

Perhaps if there were more wholesome alternatives for kids in our more deprived areas - such as swimming pools, tennis courts and velodromes - boxing's lure would be weaker. But even if there were, there would still be plenty of kids drawn to the baser thrill of testing their courage in combat.

But what of those who revel in the sight of two men or women punching each other in the head? And what does it say about us that when boxing is at its most compelling, it is also at its most dangerous, when we know exactly how dangerous it can be?

Michael Watson, who was punched into a coma by Chris Eubank Sr in 1991 and suffered life-changing injuries, external as a result, summed it up like this: "It's what people love to see. It's human nature. No different to seeing dogs fight."

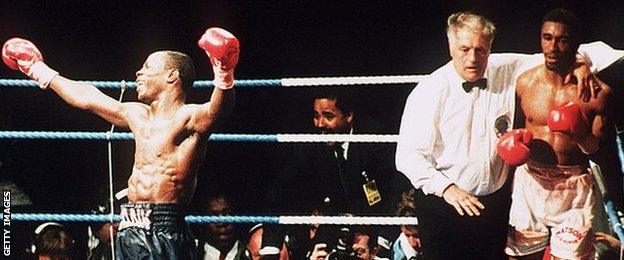

Chris Eubank won both fights against Michael Watson - the second had tragic consequences

An abolitionist might suggest that those watching the Towell fight would, in a civilised world, have been accessories to manslaughter. And the thought that a man was battered half to death while the audience laughed and drank Champagne is, at the least, discomfiting.

Furthermore, the oft-repeated argument that more people die or suffer serious injuries while racing cars or motorbikes or riding horses is naive. In all of these sports death or serious injury is, for the most part, entirely accidental. The argument that death or serious injury is entirely accidental in boxing, whose participants set out to rattle each other's brains, is far more difficult to sustain.

Which is not to apportion any blame to Towell's last opponent, Welshman Dale Evans. Towell, like Evans, knew the risks when he stepped into that ring. And Towell, like Evans, needed to be there. But when men like Towell die because of boxing, the sport becomes difficult to defend. Perhaps it means boxing people are uncivilised, which is something we just have to live with.

No amount of medical provision can stop the sport of boxing from being a threat to life. But in a tolerant society, which is what we profess to have built in this country, any thought of abolition should be resisted.

Watson still loved boxing enough to be ringside when Nigel Benn fought Gerald McClellan in 1995. That night, McClellan suffered permanent brain damage, external and was also left blind, confined to a wheelchair and requiring round-the-clock care. And Watson still loved boxing afterwards, because he knew better than almost anyone that boxing gives back more to society than it takes.

Talk to former boxers and they will complain of headaches, numb jaws, arthritic fingers and unreliable memories. And in the next sentence they will tell you that they might have not have discovered that path towards self-improvement and dignity had they not found boxing at the crossroads.

Ask a fighter the question: "Where would you be if you hadn't found boxing?" And don't be surprised if the answer is: "Dead or in prison."

Quite often, boxing fiction is rooted in cold, hard facts.

For many young people, boxing allows them to be somebody in society, rather than lead an inconsequential life of desperation. And for many young people, the idea of slowly dying behind a desk is as nonsensical as risking life in the ring.

In 1980, Johnny Owen died from his injuries after challenging for the world bantamweight title. Reflecting on his compatriot's passing, Welsh boxing great Eddie Thomas said: "It broke my heart to see Johnny lying in his coffin and made me feel that boxing isn't worth the candle. But there is something mysterious that keeps drawing you back."

In truth, there is nothing mysterious about it. Some people like to box and other people like to watch them box. If heaven exists and it is just how Mike Towell imagined it, he is probably boxing right now.

- Published3 October 2016

- Attribution

- Published1 October 2016

- Attribution

- Published1 October 2016

- Attribution

- Published19 September 2010