Jordan Reynolds: How boxing saved middleweight from life of crime

- Published

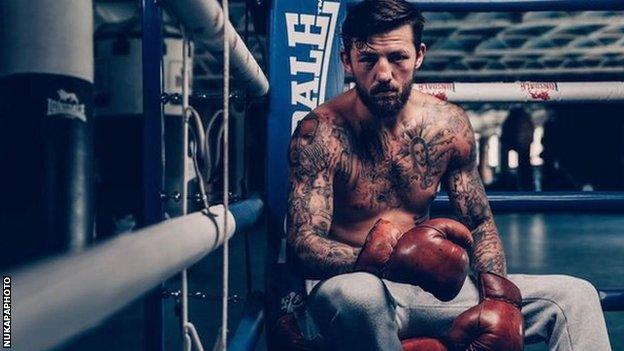

Former amateur Great Britain boxer Reynolds turned professional in March

"My best mate got shot in the back, another mate got stabbed. This wasn't the path I wanted."

For the second time in his young life Jordan Reynolds had two routes to choose from, two routes leading to very different destinations. Boxing, once again, pushed him to make the right call.

"There was a house party I didn't go to, mainly because I knew I would be tired for work and boxing," he told BBC Sport.

"I was lucky I didn't. When your best mate gets shot, and you think about the life you're getting into, it's scary."

The first crossroads came at 16 when he decided that the journey up the hill after school, to the boxing gym where he earned a few quid and found a sense of belonging, was the smart move.

The alternative was the easier, downhill option, both geographically and figuratively.

"After school I could go one way, down the hill, where I'd get involved in robbing, tormenting people in the shops and doing things I am embarrassed to have done," said Reynolds, 25., external

"Or I could run up the hill, get home then go to the gym for 4pm. That was the first step. I was always thinking 'am I on the right path?'"

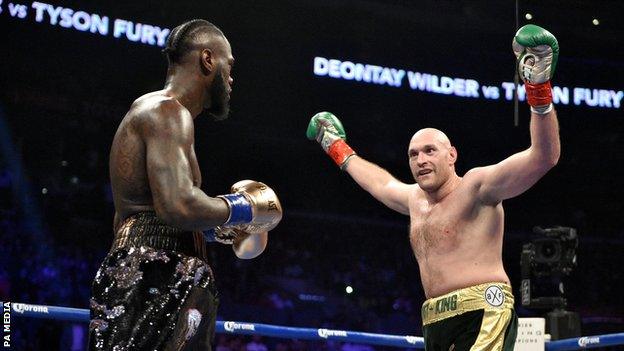

Instead of a life of drugs and crime, Reynolds would soon be keeping illustrious company with fellow national amateur champions Anthony Joshua, Tyson Fury, Carl Froch and Ricky Hatton.

Middleweight Reynolds turned professional in March and is awaiting his first pro fight in July or August after a stellar amateur career in which he won "97 or 98 of around 110 bouts".

Reynolds says he has done his schooling as an amateur and is desperate to make his professional debut

Boxing was his saviour. And because of their position as hubs in some of the country's poorest communities, boxing clubs have proved the salvation of many a young person trying to deal with mental health problems and break the mould that often envelops them.

"About 40% of clubs are in the lowest 20% deprivation areas in the country, with 50% of our clubs in the lowest 30% deprivation areas," explained England Boxing chief executive Gethin Jenkins.

"Boxing plays a huge role in these areas."

Jenkins has spent three years working for the governing body for amateur boxing in England, overseeing 971 clubs with more than 21,000 members.

The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the work they do and it's not just about the sport.

Modern technology and some lateral thinking has meant clubs have been able to continue offering support, social contact, exercise, engagement through learning and simply just taking notice of people, as well as providing what Jenkins describes as "basic human connection".

"When Covid-19 came along these clubs shut down as clubs but were opening up almost instantaneously as food banks and offering mental health support,, external not because someone told them to do it but because they recognised the need and they filled the gap," said Jenkins.

'This is what boxing clubs do'

"I have come from football and rugby and one of the clear things all along is some of the activity that goes on in boxing clubs is phenomenal.

"Coaches and the people that work there are very often parental figures, a constant in some of these kids' lives and if football or rugby did it, it would be shouted from the rooftops.

"You go to clubs and say 'why did you not make more of this?' - and they say 'this is just what we do'. They think it's normal."

A prime example of "normalising" the community role and changing lives is the Pat Benson Boxing Academy in Birmingham., external

Chief executive Paddy Benson, the grandson of founder and legendary club trainer Pat, sees the hard graft and rewards first hand.

The academy excels, both as a community organisation and a first-class boxing club.

Cianan Folan, who both boxes and works at the Pat Benson Academy, takes the lead in a Mind Fit session

"Life and career can be connected," explained Benson, 32, who boxed for England at 16.

"We have a referral pathway from GP surgeries, schools, youth offending teams and have a very good reputation within that sector.

"Our speciality is we start at the very bottom. A lot of referrals are from the age of 11-14 who could be on the periphery of getting involved in crime.

"We change their views on mental health. The boxing hook brings them in and we try to change the mindset in a disciplined, controlled and safe, non-discriminatory environment."

They offer financial assistance too, meaning relevant programmes or sessions are there for all.

"A lot of boxing clubs are doing what we do, but we do it full-time," Benson added. "But we've also got a fantastic reputation as a boxing gym. We are one of the most successful in Britain and we don't want to lose that.

"Whether you're looking at changing your life from drug addiction or being the next national champion, we are helping each individual do the best they can."

Rowan Anthony Williams reached the semi-finals in the flyweight division at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona, and former world amateur champion Frankie Gavin is also a famous old boy.

Reputation, though, means nothing. Benson says all those coming through the doors are judged on "attitude, how hard you work and your beliefs and values".

"People talk about being in gangs, but a gang is just a group of people," he added. "Often in deprived areas youngsters don't have anything to do and they are often a product of their area, the environment, family and life chances. And sometimes they are very limited.

"They turn to crime and aspirations take a hit. Identity and value is key and when that is dented self-worth goes down and then that is a problem."

'Learning to love'

Reynolds has been isolating on a training camp in Ireland

Reynolds knows the feeling only too well. The "gunfire" going off in his head was overwhelming. He could not concentrate at school, his mind overloaded with what he was seeing on the streets and at home.

"I was in a lot of trouble as a kid at school. All this emotion and negativity and the stuff going on was all I could think about when I was on my own in lessons," he said.

And he recognised the importance of talking to people and "having the confidence to speak about it and know that it's alright to do so".

"We didn't have any money," Reynolds added. "We lost our house and were really struggling. Every few days M&S would get rid of sandwiches and things - and I would be trying to get free food from the bins.

"I was the kid who would never go on holiday or on school trips because I didn't want to ask my family. This is why I have such a strong motivation. I needed to change my life. I didn't want to be that."

Boxing gave him friendship, community and a "purpose".

"You're not on your own when you go through the doors; everyone is in the same boat," he said. "You don't know anyone but you find the meaning of respect. It's such a hard game. You learn discipline and to love yourself.

"I went from an angry, frustrated kid who was full of hate to someone who couldn't hate anymore. I just wanted to love."

Reynolds, who last year opened up a boxing academy in his hometown of Luton,, external remains good mates with Swindon Town striker Keshi Anderson.

"We both came from rough areas. Both of us had no money and we are doing alright," he added.

"I'm in a good place. My life would be a lot different without boxing. There is always hope. If I can reach and inspire one person then that's amazing."

Anderson joined Swindon from Crystal Palace in 2018

- Published29 November 2021