Phillip Hughes: How does cricket move on from batsman's death?

- Published

- comments

Former Australia captain Ricky Ponting consoles Simon Katich

The cricketing world has been united in grief and shock at the death of Australia batsman Phillip Hughes.

The 25-year-old died on Thursday as a result of the injuries sustained when he was struck by a ball while batting for South Australia against New South Wales.

For a while, the sport stopped, not only to pay tribute to the talented left-hander, but also to consider if more could have been done to prevent the freakishly unusual set of circumstances that took his life.

Here, BBC Sport looks at how cricket might change in the aftermath of Hughes's death.

Click here for further reading:

Tributes to Phillip Hughes the 'uncomplicated natural'

Cricket Australia to hold an investigation over player safety

When will it be played again?

Almost immediately.

The second day of the third Test between Pakistan and New Zealand was postponed on Thursday, but that match will resume on Friday. England are set to play the second one-day international of their tour of Sri Lanka on Saturday.

But, naturally, it is in Australia where some sense of cricketing normality will be hardest to restore.

Australian captain Michael Clarke reads a statement on behalf of the family of Phillip Hughes

The Sheffield Shield match between South Australia and New South Wales was abandoned when Hughes sustained his injury, with the other two games in that round of fixtures following suit on Tuesday.

The tour match between a Cricket Australia XI and India has been cancelled, along with the weekend's Sydney club programme.

Currently, there is no mention of the first Test between Australia and India, which begins on 4 December, being cancelled, but participating in that match would be a tremendous ask for some of the Australian players who were close to Hughes.

David Warner, Shane Watson, Brad Haddin and Nathan Lyon were all on the pitch when Hughes was struck, while captain Michael Clarke read a statement from the Hughes family at a Cricket Australia media conference.

"It will be interesting to see if any players, or even a collective, say it is too soon to play," said Australian Broadcasting Corporation cricket commentator Jim Maxwell.

How might it be different?

For all the discussion of changes to the laws that govern short-pitched bowling and improvements in safety equipment, nothing, on the outside at least, will be altered in the short-term.

However, there is no telling how this could affect the mindset of cricketers of all abilities.

Those within the sport have been unequivocal in their support for Sean Abbott, the bowler who delivered the bouncer that hit Hughes.

Abbott was only doing what pace bowlers have done for as long as the game has been played - using the short ball as a legitimate tactic and method of taking a wicket. He is desperately unfortunate that this particular short delivery had such tragic consequences.

Now that the bouncer - used to intimidate for so long - has caused a fatality, might fast bowlers think twice before targeting the head of an opposing batsman?

"I've hit people before, obviously not with those terminal circumstances," said former Middlesex pace bowler and BBC cricket analyst Simon Hughes.

"It's a terrible feeling when you injure anyone in sport, even though you are trying to intimidate them."

Matthew Hoggard, who took 248 Test wickets for England, added: "As a bowler, you will think twice. What happens if it's me who delivers that ball?"

What about batsmen?

For all the talk of the bouncer being used to intimidate, Hughes - who was 63 not out when he received the fatal blow - was actually on the attack, playing a hook stroke that had brought him so many runs in the past.

Hughes was wearing a helmet, a relatively new addition to cricket having only become commonplace over the last 30 years. Arguably, they have made batsmen less likely to be wary of short bowling and, as a result, perhaps more likely to be hit.

The Analyst Simon Hughes on cricket safety

"Helmets have unfortunately taken away a lot of that fear and have given every batsman a false sense of security," wrote former England batsman Geoffrey Boycott., external

"They feel safe and people will now attempt to either pull or hook almost every short ball that is bowled at them."

Now, though, with what has happened to Hughes fresh in the mind, batsmen may be more wary of the short ball, less likely to attack with pulls and hooks, more likely to duck or weave out of harm's way.

"Phil Hughes's injuries will send shivers through cricket," wrote former England captain Michael Vaughan., external "Batsmen will now feel that while they are out in the middle they are in a world that is full of danger with the risk of serious injury."

What might change to stop it happening again?

Hughes was struck at the base of the neck in an area not covered by his helmet. That he received a blow in this region is, again, highly unusual.

Hughes was swivelling to play the hook, was on the ball too early and, by the time it reached him, he had turned to expose the back of his head - a part of the body rarely at risk of being hit. The impact at the base of the skull split one of the major arteries and caused massive bleeding.

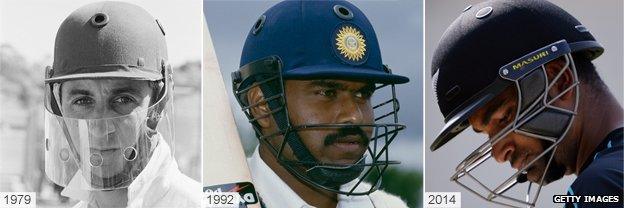

Cricket helmets have evolved since former England captain Mike Brearley's model from the late 1970s

Former International Cricket Council president Jagmohan Dalmiya has called on the game's current administrators to work on upgrading the safety of helmets, which were only recently standardised.

However, Chris Taylor, a former England Under-19 international who now works as a cricket retailer, says it is impossible for a helmet to provide complete protection.

"Once the helmet starts trying to cover the neck as well, it's going to restrict your movement as a batsman," he said., external

"You need to be able to move quickly so if it's restricting your head and your neck, we could get to the stage where you just wear full body armour because at the end of the day you can get a blow on your chest that can cause you serious problems."

Antonio Belli, professor of trauma neurosurgery at Birmingham University, also accepts that there may never be a helmet that offers complete protection and points out that cricket remains a relatively safe sport.

"We should design helmets as strong as technology allows," he said.

"But we need to accept that in cricket and other sports that involve hard objects or bodily contact there will always be freak accidents.

"For the number of hours played in cricket, it's actually considered a safe sport in terms of concussion."

Should we outlaw bouncers?

For someone outside the sport, it may seem ridiculous that a legitimate part of cricket is the hurling of a piece of leather towards the head of an opponent at speeds of up to, and sometimes over, 90mph.

However, short-pitched bowling has long been a prominent and thrilling part of the game, from the infamous Bodyline Ashes series of 1932-33 to Mitchell Johnson's performances against England last winter, via batsmen facing the great West Indies pace attacks of the 1980s with nothing more than courage and a cap for protection.

Laws to protect batsmen do exist. Sustained intimidatory bowling is policed by umpires, while no form of the game allows more than two bouncers per over to be bowled.

And, despite the tragic consequences of the delivery that struck Hughes, there seems to be no desire within cricket to ban the bouncer.

"We need to remember that is the first death we've seen," said Hoggard. "Yes, the death of a player is very tragic, but, to change the laws and the way that we play - I don't think Phil would have wanted that."

- Published27 November 2014

- Published27 November 2014

- Published27 November 2014

- Published27 November 2014

- Published27 November 2014

- Published18 October 2019