Chris Lewis prepares for most important innings of his life

- Published

Archive: Chris Lewis on his prison sentence, speaking in 2015

I meet Chris Lewis for his first media interview since his release from prison in the suite of a grand hotel on London's Park Lane. But the luxurious setting is deceptive.

Two weeks after the former cricket star walked away from Hollesley Bay Prison in Suffolk after serving less than half of a 13-year sentence for drug smuggling,, external Lewis has no income, and is reliant on the kindness of friends and family for lodgings and food.

Arranged through the Professional Cricketers' Association (PCA), which is helping the 47-year-old adjust to life as a free man, Lewis has travelled here from Willesden by bus, aware he needs to find a means of earning a living, and fast.

"Work, on a personal level, is important. I need to live," he tells me, the athlete's physique that made him such a threat with both bat and ball still intact, along with his broad smile. "I have been in jail for a long time and I need to organise my life and put it back in a place where it's actually manageable. I want to do that and actually be of some real use."

Lewis seems calm. Polite and softly spoken, there seems no anger or frustration at the years that have passed him by. His eyes light up as he recalls various cricketing memories.

Chris Lewis |

|---|

Made 32 Test appearances and 53 in one-day internationals |

Took 93 Test wickets at an average of 37.52 and scored 1,105 Test runs at 23.02, including a best of 117 |

In 1994 he shaved his head in the West Indies and suffered sunstroke, missing the first match of the tour as a result |

Born in Guyana, began his career at Leicestershire and had spells at Nottinghamshire and Surrey |

At the age of 35, he took part in the BBC television series Superstars in 2003 |

The moment of his release, he explains, was "a little bit like wearing ill-fitting shoes for a long time and then finally taking them off," adding: "It's not so much about elation, more relief because being in jail can generate an awful lot of stress in many ways. But it's not necessarily a day that you jump up and celebrate."

It could all have been so different. Back in the 1990s, Lewis seemed to have it all. A supremely gifted player, but perhaps burdened by his status as 'the next Ian Botham', the former England all-rounder appeared in 32 Tests and 53 one-day internationals, his raw talent earning him the respect of cricketers everywhere.

Even now, it is instructive to hear Ashes hero Andrew Flintoff refer to current player Ben Stokes as "the best England all-rounder since Chris Lewis".

Lewis modestly denies such comparisons. When I ask him if he was a better player than Flintoff, he diplomatically defers to the statistics - Flintoff's are significantly better., external But what a player Lewis was.

The problem was, despite the bravado and charm for which he was known, Lewis struggled to adapt to normal life after cricket, and in 2009 he hit rock bottom, convicted of smuggling liquid cocaine with a street value of £140,000 into Britain from Caribbean island St Lucia.

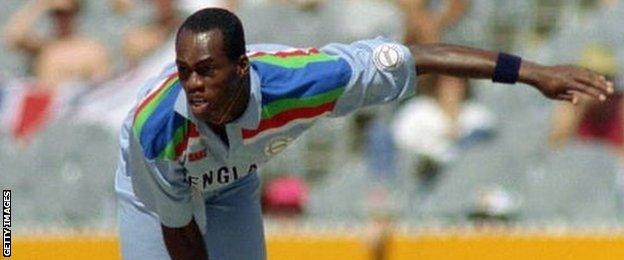

Lewis's quick, loose-limbed bowling action and combative batting style contributed to some impressive displays in the 1992 World Cup as England reached the final

He became, he says, "a little bit lost... ultimately I got myself in a place where financially, and probably emotionally, I wasn't in a good place. From that place I made really bad decisions."

Lewis, you suspect, inhabits similar psychological sporting territory as someone like a Flintoff - or a Paul Gascoigne. Sportsmen who can genuinely entertain, relying on instinct and genius rather than technique, discipline and drills, but who then struggle to replace the adrenaline and excitement once their playing days are over.

One should not feel sympathy for Lewis. The families of those affected by the kind of drugs he was trying to import will tell you he deserved all he got. His actions were as dim-witted as they were deplorable. But for a cricketer who always came across as slightly troubled, it is easy to see how it all unravelled once the bright lights of his sporting career faded.

"There was perhaps a touch of anger, maybe a touch of disillusionment at the time," Lewis says. "In order for me to take certain actions like that, I think I must have shut down half my brain."

For a free spirit like Lewis, the loss of his liberty came as a profound shock. "It was the end," he says. "At that moment it was unfathomable. But pretty soon afterwards after going back to my cell and having a cry you go: 'I am going to have to deal with this.'

"Sometimes a typical day was 23 hours locked up. That was really challenging. You're in a jail and there can be 1,000 men running around, testosterone, and everything else. It's not exactly a holiday camp. It's difficult, challenges do arise, but I think overall I have been treated reasonably."

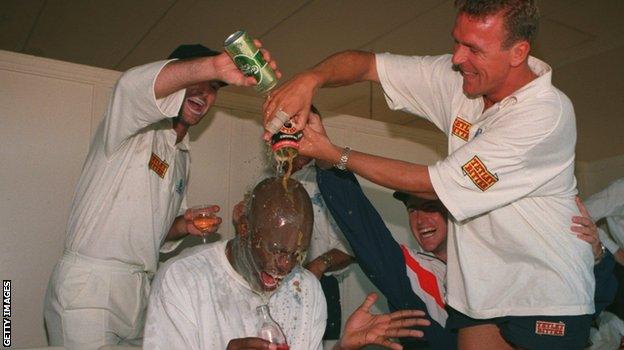

Chris Lewis was soaked in beer by team-mates Graham Thorpe and Alec Stewart after helping England beat Australia in Adelaide in January 1995

Lewis is reluctant to reveal too much about his experiences inside prison, aware that to delve too much into the past will affect his ability to rebuild his life, but it is telling that he describes himself as "calmer and happier" than before his imprisonment.

One of the ways Guyana-born Lewis hopes to rebuild his life is by using his time to speak to young cricketers - and those approaching retirement - about his experiences, helping them to avoid the pitfalls.

"Over the years I have picked up quite a bit of experience through many things and to use that to aid young professionals or young people within my community is something that I would love to do. I started off as an inner-city kid and moved into a sport that is predominantly middle class and the challenges that go with that you don't always appreciate. That's a place I can be of use."

Lewis certainly seems to have a lot to offer. His mind is undimmed, talking passionately about the need for English cricket to re-engage with Afro-Caribbean communities, about his admiration for discarded England batsman Kevin Pietersen, about how much he's looking forward to playing club cricket alongside his brothers.

Sitting in on our interview is PCA chief assistant executive Jason Ratcliffe - Lewis's former Surrey team-mate.

"He has a very important role to play in sharing his experiences," Ratcliffe tells me. "Chris's situation is acute and rare, an ex-England player serving time for his crime. We know that case studies such as this will be powerful at pre-season county visits because players listen to players. We hope his story will reaffirm that all players need to pay attention to their futures.

Chris Lewis made his only Test century on his 25th birthday, against India in 1993

"I'm confident he'll be OK, not least because it seems there is a lot of support for him. However, it won't be straightforward and he'll need to work hard and find a routine. Not everybody will welcome him with open arms. However, he has admitted his mistake, apologised and paid a significant penalty. He should now be afforded a second chance."

Lewis was concerned the world of cricket would shun him after his release. After all, he always felt he was effectively driven out of the game after he made unsubstantiated allegations in 2000 that three England players may have been involved in match-fixing,, external something that saw him criticised by fans and players alike, and which even now he refuses to talk about. He even went on strike, external in protest at what he saw as being hung out to dry by the England and Wales Cricket Board.

But, so far, the abandonment he feared has not come to pass.

"Everyone has been really gracious," he says. "I've been a little bit overwhelmed. There is that fear that when you make a mistake you have to accept that other people will also make choices. People generally do not want to be associated with drugs. It's the fear of non-forgiveness. But they have shown me a lot of warmth."

Even so, Lewis admits he may not be ready to attend an Ashes match this summer. Instead, he says, he will just watch on TV. "The sort of readjusting I'm doing is readjusting to people. That process will take some time."

I ask Lewis whether he resents the fact that had he played cricket today, he would almost certainly have been a millionaire. The modern game would have loved Lewis. The Indian Premier League (IPL) would have come calling, endorsements and sponsorship deals would have flowed. Does he wish his career had come 20 years later?

He was in and out of the England team throughout the early and mid-1990s

"No. I certainly wish I had been paid the same money that the guys are earning today," he smiles. "But, to be honest, compared to working somewhere else, I thought I was reasonably well paid. There's no need to be bitter about it. I think mistakes were made by me. I smile when I see IPL money. But I'm smiling in a positive way."

Lewis was always seen as a player who did not quite live up to his potential. But maybe it is that relaxed, carefree attitude to life that now enables him to cope with his spectacular fall from grace.

"Certainly there are things I would do differently to make more of my ability," he admits. "But I think actually I did quite well. I played for England in a World Cup final. As a boy growing up, if someone had offered me that, what would I have said? My dream was just to play cricket. I'd outdone myself."

No-one would blame Lewis for wallowing in self-pity. For dwelling on his downfall. To be racked by regret. And yet he seems positive. Perhaps he has no choice.

"At the moment I'm going 100mph now that I'm free," he says. "Perhaps at some point in the near future that'll catch up with me. More than anything else I'm actually excited. There can be trepidation but the overall feeling is a feeling of opportunity. Even though I am not a young man, I think I am still looking at things positively. I'm free."

It used to be said that for all his ability, Lewis regularly failed to deliver for his country. Now, more than ever, he needs to deliver for himself. This next innings is the most important of his life.

- Published23 June 2015

- Published23 June 2015

- Published22 June 2015

- Published22 June 2015

- Published22 June 2015