Lance Armstrong: Legal opinion divided on case

- Published

The International Cycling Union (UCI) says it has been contacted by up to 20 sports lawyers offering free legal representation following the decision of the United States Anti-Doping Agency's (Usada) to ban Lance Armstrong for life for doping offences.

Usada said on Friday it was annulling the American's results since 1 August 1998, including the record-breaking seven Tour de France titles he won between 1999 and 2005.

But the UCI, cycling's governing body, is yet to endorse the sanctions and has asked Usada for a "reasoned decision" before taking any action.

Usada alleges Armstrong used banned substances as far back as 1996, including steroids, blood transfusions and the blood-booster erythropoietin (EPO).

The US cyclist strongly denies the claims but opted not to contest Usada's drugs charges, saying he is tired of fighting the allegations.

In the five days since Usada's judgment, the UCI says numerous lawyers have offered to challenge the agency's right to unilaterally apply sanctions.

The BBC understands that the UCI is now weighing up two specific offers from UK-based lawyers.

Dr Gregory Ioannidis, a senior lecturer in sports law at the University of Buckingham, believes the UCI should take its case against Usada to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (Cas) in Lausanne.

"From a legal standpoint, Usada does not have jurisdiction to apply sanctions on an athlete, particularly as these allegations concern non-analytical findings [they are based on witness testimony, not positive tests] in a case of international dimensions," he said.

"Its decision to 'strip' titles means nothing without the UCI's official confirmation. As things stand, Armstrong is stripped of nothing."

Trevor Watkins, head of the sports division at international law firm Pinsent Masons, agrees that "fundamental issues about the structure of sport" are at stake.

"It is right that Usada should ensure we have a level playing field and its role is clear," he said. "But the UCI's role, as the international federation, is also clear.

"What's not clear is what happens when one body tries to impose a judgement on the other. We need to know who does what.

How does blood doping work?

"The perception is that Usada has been prosecutor, judge and jury."

Usada believes Armstrong has, in effect, accepted its claim he was at the centre of a doping conspiracy by refusing to contest its evidence against him in front of an independent panel.

The 40-year-old Texan continues to protest his innocence and says only the UCI has the right to remove him from the sport's record books.

The UCI had previously challenged Usada's right to proceed against Armstrong, writing to the agency's chief executive Travis Tygart, demanding that he submit whatever evidence he has to a panel set up by cycling's world governing body.

The UCI has since dropped this demand under pressure from the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada), the main organisation in the fight against drugs in sport, and the International Olympic Committee (IOC), which runs the Olympic Games and provides Wada with half of its funding.

Usada's right to lead the investigation was strengthened when a US federal court threw out Armstrong's attempt to halt the process on the grounds that the Colorado-based body did not have the authority to act against him and its arbitration procedures were "unconstitutional".

US district judge Sam Sparks dismissed these claims, but highlighted the potential for future legal disputes when he noted the "appearance of conflict" between the UCI and Usada.

The BBC has spoken to another leading sports lawyer who is scathing in his criticism of the UCI's role in this process.

The lawyer, who wished to remain anonymous as he has a professional interest in the case, said Wada's rules do not give an international federation seniority over a national anti-doping agency in cases of this type.

He also pointed out that Usada was within its grounds to push on with its investigation under the UCI's own "discovery rule", which states that whichever agency comes into evidence of cheating has the authority to pursue the case.

He also believes the governing body's position has been compromised by suggestions it was complicit in Armstrong's cheating.

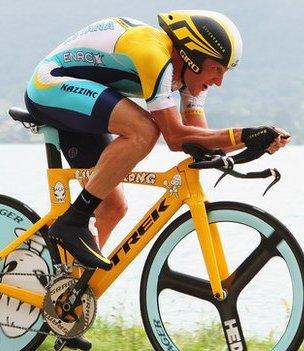

Lance Armstrong spoke about the drug allegations in February 2011

The only area he felt the UCI might have an argument is on the length of time it has taken to Usada to apply sanctions. Sport usually has an eight-year statute of limitations.

Nevertheless, the lawyer feels Usada could win this debate as well given it is likely to argue that Armstrong lied about his wrongdoing and therefore did not deserve the benefit of the eight-year limit.

There is one key issue that everybody agrees on, though: the UCI's decision to effectively come out in support of Armstrong will not only be based on the legal merits of its case.

With the IOC, Wada and cycling fans around the world watching closely, the UCI must weigh up the political costs of backing such a divisive figure, particularly if the evidence he has sought to contain reaches the public domain anyway.

- Published24 August 2012

- Published24 August 2012

- Published20 August 2012