Lance Armstrong two years on - the same, but different

- Published

Lance Armstrong is interviewed by BBC sports editor Dan Roan

Look into his eyes and you notice it.

At first glance, Lance Armstrong is as he always seemed: supremely fit, ultra-confident, smart and eloquent.

But look into the whites of his eyes from a few feet away, as I did when we spoke at length in Texas last week, and you see it - a weariness, at times even a sadness. It is then you see the subtle but inevitable toll sport's most spectacular fall from grace has taken.

Armstrong on drugs, history and the future

Armstrong's infamous doping confession to Oprah Winfrey two years ago shattered sport's greatest fairytale. Now, after months of negotiation, he had finally agreed to meet for his first television interview since that day in January 2013.

It would happen on familiar ground for the 43-year-old, Mellow Johnny's - the bike store he owns in Austin, the city in which he has kept his head down since he went from the ultimate all-American hero to pariah.

The meeting would take place after dark, once the shop had closed, and no customers or passers-by could cause any grief.

We were politely asked to try to avoid filming him with any of the Trek bicycles on display. Trek had quickly cut ties with Armstrong after he became toxic. A little too quickly for Team Armstrong's liking. They saw it as an act of treachery after he had done so much to boost their sales.

As we waited for him to arrive, it was hard to know what to expect.

After all, not so long ago, Armstrong had everything., external Having beaten cancer, the Texan became a global sporting icon for the 21st century, winning perhaps sport's most gruelling event, the Tour de France, seven times in succession.

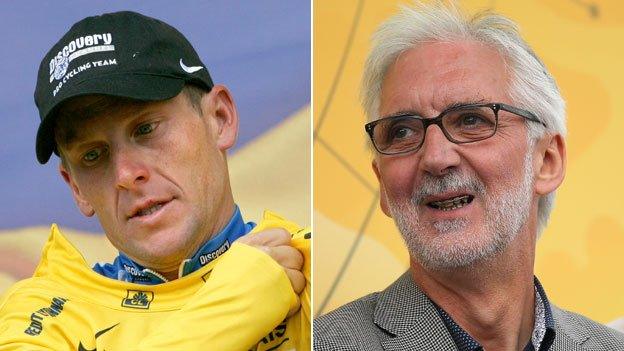

The Lance Armstrong story | |

|---|---|

Born: Plano, Texas on 18 September 1971 | |

Tour de France victories: 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 (22 individual stage wins) | |

World Championships road race victory: 1993 | |

Cancer survivor: Diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1996. The disease spreads through his body. Launches Lance Armstrong Foundation for Cancer. Declared cancer-free in 1997 after brain surgery and chemotherapy | |

Retirement: Announces he will retire after the 2005 Tour de France, which he wins. Angered by drug allegations against him, Armstrong announces in September 2008 he will return to professional cycling. In June 2010, he reveals via Twitter that the 2010 Tour de France will be his last. On 16 February 2011, Armstrong announces retirement again. |

He made millions from sponsorship deals, and helped raise even more through the Livestrong cancer charity he founded. He took cycling in the US from the margins to the mainstream, had a private jet, was engaged to rock star Sheryl Crow, and even made cameo appearances in Hollywood hits.

Armstrong was a living legend. Then came the great fall.

After years of suspicion, allegations and denials, Armstrong was finally exposed as a fraud, the ringleader - according to the US Anti-Doping Agency (Usada) - of "the most sophisticated, professional and successful doping programme sport had ever seen".

He was there alongside Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson in the race for the title of sport's most notorious cheat.

Ben Johnson was stripped of his 1988 Olympic 100m gold medal after testing positive for anabolic steroids

Armstrong was banned from sport for life, stripped of his Tour wins, kicked out of his own charity, and deserted by his sponsors.

He had lied under oath, sued journalists he knew had been right, and ruthlessly bad-mouthed former friends who stood up to him. His subsequent confession to Oprah only made things worse, Armstrong coming across as unrepentant, evasive and arrogant.

And now he was on his way to meet us. His first tentative steps towards what he hopes will be an unlikely redemption.

Had he become a recluse? Was he broke? Depressed? Wracked with self-hate?

Far from it.

Armstrong arrived. An hour late, after dinner with his family, but he had honoured his agreement.

He was polite, friendly, fixing us each with that hypnotic stare, the charisma intact. He seemed to have everything under control, doing just fine.

But then I looked him in the eye, and saw that damage had been done.

The fallout, he told me, had been "brutal".

His biggest fear is that one of his older kids will get hassle at school and come home "in pieces". It has not happened yet, but will "rock him" when it does.

The "deepest cut" had been Livestrong severing ties - "it doesn't get worse than that".

Armstrong founded the cancer support charity Livestrong in 1997. He resigned as a board member in November 2012

Lawyers still make up his "top three calls every day" and boredom is an issue now his life has gone from "100 to 10mph".

But life is far from unbearable either. Armstrong still runs six-minute miles and plays golf every day.

He remains a very wealthy man. The financial ruin that many predicted has been avoided. Despite the loss of his many sponsorship deals and several legal settlements, he still has millions in the bank.

He may have had to sell the $10m (£6.6m) mansion overlooking the Colorado River in Austin's most exclusive neighbourhood, but he still has a beautiful home close to downtown, as well as other houses in Aspen and Hawaii. A federal lawsuit worth as much as $120m (£79.9m) hangs over him, but his people seem confident.

But has Armstrong learnt from his mistakes? Was he more contrite two years on?

There was no shortage of apparent remorse, especially for the vicious way he treated people when covering up his doping.

He admitted he had been "a complete **** to a handful of people" and "that's something I need to spend the rest of my life trying to make right".

He has tried to apologise to them, continues to do his bit for the local cycling community and sends messages of support to people with cancer, many of whom still regard him as an inspiration. He is clearly a devoted father to his five children, and seemed to be looking forward to the school run the following morning.

Yet, in other areas, Armstrong remains defiant. He clearly wants his life ban lifted.

"Of course I want to be out of timeout. Has it gone too far? Of course I'm going to say yes," he said.

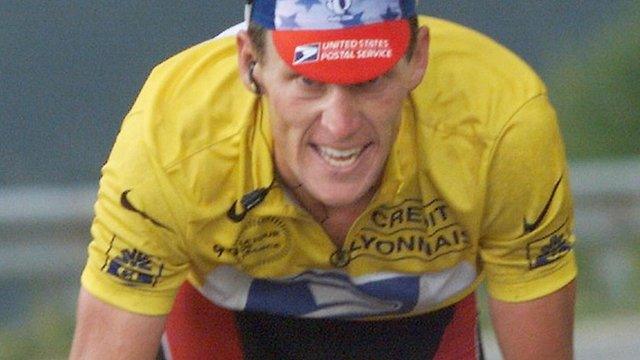

Armstrong celebrates his seventh successive Tour de France victory in 2005

On the issue of his titles, which he still regards as legitimate, he wants them back: "I feel like I won those Tours."

And on the subject of forgiveness. "We're getting close to that time".

Many will be appalled at the suggestion. But polarising opinion is what Armstrong does like no-one else in sport.

His argument is familiar: it could not be cheating when practically the whole of the peloton was doping too, a "collective decision".

He has a point. Over his seven-year reign at the Tour between 1999 and 2005, an incredible 87% of the top-10 finishers were confirmed dopers, or suspected of doping.

It is on this basis Armstrong believes he has been harshly treated, with other dopers given shorter bans, and keeping their titles while he lost his.

"Haven't we got to look at the whole play?" he asked.

That inconsistency is wrong, he said, adding the fact he cannot take part in organised events like marathons, and raise money for good causes.

Cycling must be credible - Sir Dave Brailsford

But what example would it set if his sanction was reduced? Yes, he raised vast amounts for charity. But are punishments such as his not meant to act as a deterrent?

"At the expense of others?" he countered. "I don't think anybody thinks that's right. I want to get back to a place where I can help people."

The ban, he argued, ignores the greater good, preventing him from the opportunity to make amends and rehabilitate his reputation in a way the likes of former US President Bill Clinton have.

Over the course of the next hour and a half, I put it to Armstrong that far from being the "level playing field" he recalls, the tragedy of doping is that no-one knows if he was the best rider (which he may well have been), or just the best cheater.

I suggested he might want to take down the seven yellow jerseys that hung defiantly on a wall above us; that he had "led the band" as he admitted, that the other cyclists had not lied under oath or bullied friends, like he had; and that crucially the others had co-operated with Usada, whereas he refused. In short, that he absolutely deserved a heftier punishment.

Against each of these charges, Armstrong listened, thought briefly, and had none of it.

The team-mates who testified against him, he insisted, had been offered a deal he was never granted. He had been a scapegoat for an entire generation, a prize scalp.

"Usada needed a splash," he said. He was, he added, the victim of an agency hell-bent on taking him down and proving its worth at a time when its funding was under threat.

Armstrong, as always, was fighting. Even now he knows no other way. Fighting was how he escaped his troubled upbringing in Dallas, the way he had beaten cancer, and the way he dealt with those who accused him of cheating.

But such have been the lies over the years, it is hard to know what to believe.

Lance Armstrong admits doping to win cycling titles

I asked Armstrong if he was any clearer now than he had been with Oprah over his alleged admission of using drugs in an Indiana hospital back in 1996.

His 'no comment' to that question had dismayed his former friend Betsy Andreu, who has always maintained the incident happened.

This time, Armstrong told me he simply could not remember. That will anger Andreu, who recently said on Facebook "the Armstrong delusion is alive and well".

He stuck rigidly to his insistence - widely considered implausible - that he rode clean in the 2009 and 2010 Tours when he made his comeback after retirement.

People think you're still lying, I told him. "I've got patience on that," he responded calmly.

Many will point to other exchanges in our interview, and conclude he remains in denial. But what is certain is that Armstrong has met twice with the Cycling Independent Reform Commission (CIRC), set up by governing body the UCI to investigate cycling's doping past, and insists he answered all their questions.

Meanwhile, both UCI president Brian Cookson, external and Travis Tygart, head of Usada, have been making positive noises about the possibility of his ban being reduced if he finally explains how the doping was orchestrated.

"I think about it every day," said Armstrong about the report CIRC is set to complete next month. It is expected to paint a bleak picture of the entire era Armstrong rode in, and could even recommend that Armstrong's ban be reduced in return for his co-operation.

Bjarne Riis admitted using the banned blood-boosting drug erythropoietin (EPO) during his career but is still listed as a Tour de France winner

But while cycling hopes to draw a line under its past, if it thought Armstrong's demise symbolised a decisive victory in the war against drugs, it was sadly mistaken.

The UCI has been criticised for giving the Astana team a licence to race this season despite a number of positive tests, and Usada has just combined with anti-doping agencies in Denmark and Netherlands to ban former Rabobank and Team Sky doctor Geert Leinders for life.

The spectre of performance-enhancing drugs continues to hang over this sport and others, as the recent allegations of institutionalised doping in Russian athletics prove.

It is in this climate, then, that Armstrong wants to at least start a conversation about his ban.

Some will argue the real question is not how long his ban should be, but whether he should be in jail. They say this is all a smokescreen, and that the only role Armstrong should play in sport now is as an example to others.

Others, however, recognise the inconsistency in Armstrong's inability to run a marathon for charity, while confessed doper Bjarne Riis,, external to pick one example, is still in the records as the 1996 Tour winner.

Armstrong in 2009: "I know what I did and did not do. I sleep at night."

Many would prefer it if Armstrong just faded away, and the media - including us - lost interest in him.

Interviewing such an extraordinary individual was a compelling experience, but also a strangely sad one. This is not how we want to see our sporting heroes: inspirational athletes talking about regret and contrition make for uncomfortable viewing.

At his peak Armstrong personified hope, but now he causes unease, a reminder of our own weaknesses.

Who among us can be sure that faced with the same circumstances, we would have resisted the temptation to cheat? And why were most of us so easily duped? Should we give him another chance? The Texan forces us to confront difficult questions.

There is something of the Shakespearean villain about Armstrong. There is certainly good there as well as bad. It is not black and white.

Scorned and spurned, jilted and angry, he implores us to understand. Part of you wants to believe he is truly sorry. But the backstory prevents you from doing so.

For many, Armstrong needs to show genuine remorse for doping in the first place. The irony is that this would require him to lie. His admission that he cannot regret something he feels he had no choice but to do, and which he still sees as a means to an end, will disappoint many.

His biggest mistake, he said, was the comeback in 2009. Without that the myth would have been preserved.

That, I told him, may be the honest answer, but it reinforces the view he is only sorry for being caught, rather than doping in the first place.

"I get that," he said. "I think we're all sorry we were put in that place."

For many, that is simply not good enough.

Lance Armstrong was third behind Alberto Contador on his Tour de France return in 2009

Not everybody cheated, I reminded him, and if refusing to dope would have meant leaving the sport, he would have done so with his integrity intact.

"I know very few people that are left with their integrity, then," he countered. We were done.

Do not be surprised if one day Armstrong is accepted back into the sport. America loves a comeback story, after all. Many Texans I met believe it is time to move on.

But forgiveness usually hinges on contrition, and when it comes to the doping, Armstrong clings to the idea that he was more sinned against than sinner. Maybe he has no choice. Perhaps it is that belief that enables him to carry on.

But the danger is that it may stand in the way of redemption.

The road back for Lance Armstrong could be a long one.

A 30-minute documentary, Lance Armstrong: The Road Ahead, will be broadcast on BBC News at 20:30 GMT on Thursday, 29 January, and again over the following days on that channel and BBC World News. An extended edit of Dan Roan's interview will also be available on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published27 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015