Lance Armstrong: I'd change the man, not decision to cheat

- Published

Armstrong on drugs, history and the future

This story contains language you may find offensive.

Shamed cyclist Lance Armstrong believes the time is coming when he should be forgiven for doping and lying - and told the BBC he would probably do it again.

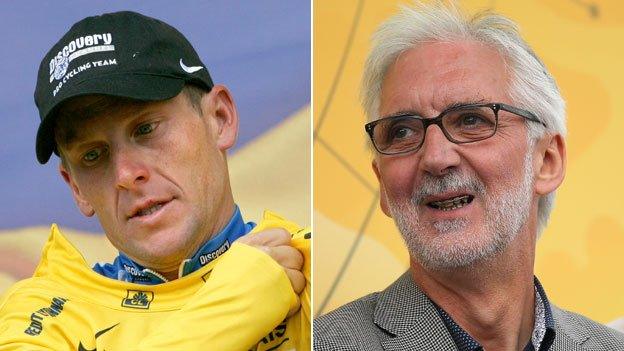

Armstrong, 43, was stripped of his record seven Tour de France titles and banned from sport for life by the United States Anti-Doping Agency (Usada) in August 2012.

"If I was racing in 2015, no, I wouldn't do it again because I don't think you have to," he said.

"If you take me back to 1995, when doping was completely pervasive, I would probably do it again."

Speaking in his first television interview since confessing to Oprah Winfrey that he had used performance-enhancing drugs during his career, Armstrong tells BBC sports editor Dan Roan:

The "fallout" since his confession has been "heavy" and he now lives his life at 10mph, not 100.

His decision to dope was "bad", but taken at "an imperfect time".

He still feels like he won the seven Tour titles he was stripped of.

He raced clean during his second comeback in 2009 and 2010.

Armstrong had been the subject of doping allegations since he returned from cancer in 1996 to dominate one of the world's toughest events from 1999 to 2005.

He aggressively denied the claims until Usada's 200-page "reasoned decision" - complete with 1,000 additional pages of evidence - was released in October 2012.

Armstrong finally confessed in a two-part interview with US talk-show host Winfrey in January, 2013.

He was forced to step away from the cancer charity he had founded and has since kept his counsel, save for a handful of print interviews.

Speaking in his hometown of Austin, Texas, Armstrong said "the fallout" from his confession had been "heavy, tough, trying and required patience".

The father-of-five said his life had "thinned out" and "slowed from 100mph to 10", but added he would like to return to "50, 55".

Lance Armstrong - the titles | |

|---|---|

Tour de France titles (later stripped): 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 | |

World Championships road race: 1993 |

As for whether the world was ready to accept his return to public life, Armstrong said: "Selfishly, I would say 'yeah, we're getting close to that time'.

"But that's me, my word doesn't matter any more. What matters is what people collectively think, whether that's the cycling community, the cancer community.

"Listen, of course I want to be out of timeout, what kid doesn't?"

Armstrong was asked if he would make the same choice to cheat that he made in 1995.

He said: "When I made the decision, when my team made that decision, when the whole peloton made that decision, it was a bad decision and an imperfect time.

"But it happened. And I know what happened because of that. I know what happened to the sport, I saw its growth."

Armstrong said sales at his bicycle supplier Trek Bicycles went from $100m (£66.5m) to $1bn and his charity foundation went from "raising no money to raising $500m, serving three million people".

He added: "Do we want to take it away? I don't think anybody says 'yes'."

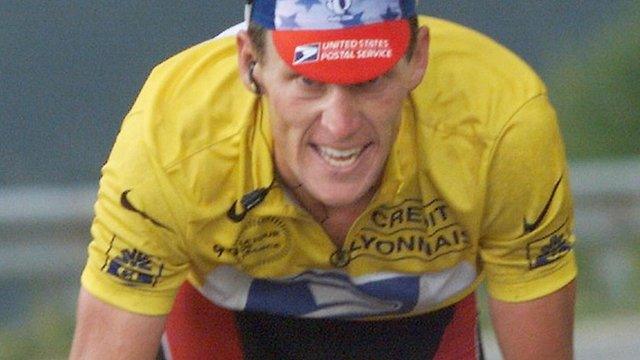

Armstrong finished a record seven Tour de Frances wearing the yellow jersey

Armstrong did admit to "unacceptable and inexcusable" behaviour towards other people during his career.

Former rider Filippo Simeoni angered Armstrong by testifying against his coach/doctor, Michele Ferrari, in a 2002 Italian doping case. The American called him a liar and denied the Italian a stage win in the 2004 Tour.

Armstrong also responded with legal threats and personal smears when Emma O'Reilly, a masseuse at his US Postal team, provided some of the earliest details on his doping.

"I would want to change the man that did those things, maybe not the decision, but the way he acted," he continued.

"The way he treated people, the way he couldn't stop fighting. It was unacceptable, inexcusable."

He added he had been "an arsehole to a dozen people" and had spent the past two years trying to make amends, with varying results.

Armstrong was equally forthright on what should happen to his Tour titles, which have not been reallocated, such was the extent of cycling's doping problem at the time.

"I think there has to be a winner, I'm just saying that as a fan," he said.

"There's a huge block in World War One with no winners, and there's another block in World War Two, and then it seems like there's another world war.

Armstrong was third in the 2009 Tour de France, and 23rd 12 months later

"I don't think history is stupid, history rectifies a lot of things. If you ask me what happens in 50 years, I don't think it sits empty... I feel like I won those Tours."

Armstrong reiterated his promise that he raced clean during his second comeback in 2009 and 2010, contrary to Usada's report, and said he would be the first to release his samples for retesting as soon as a test for blood transfusions is developed.

He also confirmed he has spoken to the Cycling Independent Reform Commission (CIRC) on two occasions and is now waiting to see if it will recommend a reduction in his ban, something that would allow him to "compete in some sport at a fairly high level", but also raise money for charity.

Armstrong was less forthcoming on his legal battle with former team-mate Floyd Landis and the Department of Justice. That case, which hinges on whether his team's sponsor, the US Postal Service, was defrauded of almost $40m (£26.5m), is unlikely to be heard in court until 2016.

But he admitted the strain of his legal problems was telling, and he looked forward to a time without lawyers and worries about what his children might hear at school.

A 30-minute documentary, Lance Armstrong: The Road Ahead, will be broadcast on BBC News at 20:30 GMT on Thursday, 29 January, and again over the following days on that channel and BBC World News. An extended edit of Dan Roan's interview will also be available on the BBC iPlayer.

- Published27 January 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015