Bradley Wiggins on the UCI Hour Record and racing against history

- Published

Wiggins 'obliged' to attempt hour record

Bradley Wiggins hour record attempt |

|---|

Venue: Lee Valley Velo Park Date: 7 June Time: 18:30 BST |

Coverage: Live text commentary from 18:00-20:00 BST |

When you talk to people who have tried to break the UCI Hour Record, you often hear the words "pure" and "simple", and as a test of athleticism it is hard to find anything that comes close.

But keep listening and soon you hear "cruel" and "painful", too, because there is a downside to a race without obstacles and unknowns: there are no excuses.

The only debate before Bradley Wiggins attempts the record on Sunday however, has been about by how much he will beat the record, held by English compatriot Alex Dowsett at 52.937km, or 32.89 miles.

But would 52.938km equal success for a man with as keen a sense of cycling's history - and his place in it - as Wiggins?

A chance to make history |

|---|

Only five riders have managed to claim the Tour De France title and break the UCI hour record |

They are: Lucien Petit-Breton (France), Fausto Coppi (Italy), Jacques Anquetil (France), Eddy Merckx (Belgium) and Miguel Indurain (Spain) |

"It's such a historic record when you think about the people who have gone for it before," said Wiggins in London this week. "The likes of Eddy Merckx, Francesco Moser, (Fausto) Coppi, (Jacques) Anquetil - some of the greatest cyclists who have ever lived

"And as a Tour de France winner, and Olympic and World time-trial winner, I almost felt a little obliged to go for it.

"You're racing against history. The basis of the record hasn't really changed, it's one hour, on a track, as far as you can go."

Britain's Alex Dowsett is the current record holder after setting the new mark in May 2015

The goal

Wiggins has never shied away from a challenge, and he enjoyed proving wrong those who laughed at the idea of him winning a Tour, as well as those who thought he would never again beat his great German rival Tony Martin in a long time trial.

So it is with customary chutzpah that he has revealed he is aiming for 55.25km (34.33 miles), which would be nine 250m laps further than Dowsett managed.

Alex Dowsett breaks iconic hour record

The Essex boy's mark is about the width of a football pitch short of 53km and it was set by the 26-year-old in Manchester last month.

Dowsett might lack Wiggins' mainstream clout but, as a three-time national and the current Commonwealth time-trial champion, his name is not out of place on the honours board, a list that began with another Englishman, James Moore, and his penny-farthing on a track in Wolverhampton in 1873.

The challenge

Scotland's Graeme Obree, the record's great romantic, described it as like drilling holes in your own teeth. His English rival Chris Boardman, the great pragmatist, said you ride around in circles until someone says stop.

"I split it into three 20-minute parts," said German Jens Voigt, who broke the record in 2014.

"The first part was pretty smooth. I started fast and was quickly ahead of the schedule. I was motivated, I was sharp.

"For the next 20 minutes I wanted to go into cruise control. Maintain my speed, concentrate on staying aero, but not pushing too much. And then the last 20 minutes was meant to be all in."

Jens Voigt signed off from a fine career by setting a new record at the age of 43

It did not quite go to plan - Voigt was too conservative in the middle and lost almost a lap - but he did not "crack" and he got his record.

"Everything hurts but I really struggled with the place you're sitting on, however you want to call that," Voigt continued, looking uncomfortable just thinking about it.

"That really killed me. But my shoulders hurt from keeping the position, and my neck. My breathing was controlled but my thighs and glutes were really hurting. I couldn't go up or down stairs for four days afterwards."

The pain

The issue of how much the hour hurts is worthy of a psychology thesis.

Belgian legend Eddie Merckx hated it, Boardman suffered horribly in his first and third attempts, Obree failed first time but came back the following morning after a night of stretching to beat it, while Dowsett was annoyed he had not completely emptied his tank.

Having spent the last 10 weeks preparing for this, Wiggins says he is ready for the mental examination and has followed Boardman's advice to do long dress rehearsals: 30-minute efforts, then 40 and most recently a 45-minute test.

"It's going to be one of the hardest things I've ever done," the 35-year-old Londoner said.

"And I don't know what those last 10 to 15 minutes will feel like. I think they will be like the last 100m in a 400m, you die or you carry on.

"You're doing what the greats have done. They got up and said 'this is going to hurt'. I like that. I can compare myself to what Eddy Merckx did in 1972 and Chris Boardman in 1996."

Belgium's Eddy Merckx has the most Grand Tour victories in history with 11

The legend

That is a good way to introduce arguably the most famous and significant attempt on the record.

Like Don Bradman in cricket and golf's Jack Nicklaus, any serious debate about cycling's 'greatest ever' starts and finishes with the Belgian Merckx; and many devotees of the hour record feel the same way about the 49.431km he rode in 1972.

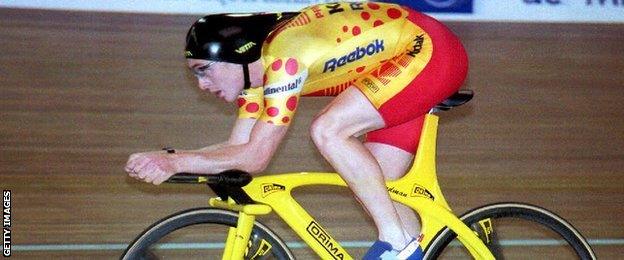

Fausto Coppi was known as 'Il Campionissimo' in Italy, which translates to Champion of Champions

Superstars attempting the record were nothing new. Italy great Fausto Coppi took it in 1942 when he rode 45.798km while Allied bombers provided the soundtrack outside the Vigorelli velodrome.

Fourteen years later, the next star came along, Frenchman Jacques Anquetil squeezing another lap or so into his allotted time.

However, while it was novel that Merckx did it on an outdoor track more than 2,000m above sea level in Mexico City, it was also traditional in that he did it on a steel bike, with drop handlebars and round spokes.

Jacques Anquetil became the first cyclist to win the Tour De France five times, in 1957 and then from 1961-64

It also hurt him, a lot.

One of the toughest men to ever throw his leg over a saddle had to be held up as he was led away, too tired to talk, let alone celebrate. Words, when they came, told of a harrowing experience. He would later say he was never the same rider again.

His record also had longevity. Whether his peers were scared of his CV, or his account of what it felt like, they stayed away for 12 years, until Italy's Francesco Moser stretched the record by a mile in 1984 at the same venue.

The big difference was that Merckx rode a beautiful, hand-built version of the type of bike you can still find in garages.

Moser, on the other hand, turned up with a cutting-edge bike, disc wheels and Professor Francesco Conconi, a sports scientist who would go on to become infamous for introducing EPO to the sport.

The UCI Hour Record had entered its "man or machine" era. The governing body would spend the next 30 years agonising over its implications.

Selected UCI hour world record landmarks* | ||

|---|---|---|

Year | Rider | Distance |

1893 | Henri Desgrange | 35.325km |

1898 | Willie Hamilton | 40.781km |

1935 | Giuseppe Olmo | 45.090km |

1942 | Fausto Coppi | 45.798km |

1956 | Jacques Anquetil | 46.159km |

1972 | Eddy Merckx | 49.431km |

2000 | Chris Boardman | 49.441km |

2005 | Ondrej Sosenka | 49.700km |

2014 (Sep) | Jens Voigt | 51.115km |

2014 (Oct) | Matthias Brandle | 51.850km |

2015 | Alex Dowsett | 52.937km |

*Does not include those cancelled from record books by UCI | ||

The rivalry

Graeme Obree was an amateur rider who ate marmalade sandwiches for energy and used washing-machine parts in a bike he built in his kitchen.

Chris Boardman was the individual pursuit champion at the 1992 Olympics, known for his methodical approach to training and interest in the latest developments in equipment.

And from the moment Obree rocked up in Norway, almost unannounced, to break Moser's mark a week before Boardman's long-announced attempt in Bordeaux in 1993, they were transformed into cycling's answer to Seb Coe and Steve Ovett.

A film about Graeme Obree's attempts on the record was produced in 2006, named The Flying Scotsman

Obree's record-breaking ride is a story in itself - and inspired one of the better sports films of recent years, "The Flying Scotsman" - but Boardman would smash his distance.

Nine months later, Obree was back, and this time it was his turn to take the record out another 500m.

But Obree was not the record-holder for long as the big guns arrived in the shape of Miguel Indurain, the third five-time Tour winner to feature on the list, and four-time Grand Tour champ Tony Rominger.

The Swiss star's second attempt in 1994, a stunning 55.291km, seemed to be one of those performances that put the record back on the shelf for a generation.

But Boardman was not done.

Two years later, using Obree's controversial "Superman" position, he put in what he has described as the most perfect performance of his career to ride 56.375km.

Chris Boardman broke the world hour record three times and was an Olympic champion in 1992

The rewind

It might have been perfect but it terrified the cycling authorities. It was time to take back the record from the sports scientists, ditch the aero bars and fancy wheels, and get back to the basics of lungs, muscles and suffering.

At a stroke, Boardman's best was reclassified as the "best human effort" and an "athlete's hour" was reset to Merckx's 1972 landmark.

If this sounded like the bosses were not that impressed with Boardman's effort, he responded in the best way possible by swapping his techno kit for a Merckx-style bike in 2000 and beating the Belgian's distance by 10m. It was his finest hour.

And then….nothing.

Well, nothing apart from Czech rider Ondrej Sosenka taking Boardman's "athlete's hour" record in 2005, an achievement that would have received more praise if he had not been caught doping twice in separate events.

The return

"I didn't want to give the impression I was easing into retirement, kind of sneaking out of the sport," explained Jens Voigt.

"I wanted to be 'stupid old Jens' one more time, giving the fans something to laugh about. I wanted to go out with a bang."

The bang came when Voigt became the first rider to take advantage of a decision the UCI announced a year ago, slightly sheepishly, as if it was embarrassed it had taken it so long to come up with it.

Jens Voigt made his attempt on the hour record just one day after his 43rd birthday

No longer would attempts have to be made on old-fashioned road bikes; you could now use modern pursuit bikes, with tri bars and disc wheels. The 21st century had arrived.

So one day after his 43rd birthday, in his last professional outing, and despite not having any real pedigree against the clock, Voigt made the first attempt under the new rules.

All he had to do was beat Sosenka's 49.700km - not a given when you consider it took him three days of practice to get around the first bend without sitting down on his saddle again, convinced that his pedal was going to catch on the wooden banking.

"I hadn't ridden on a track for five or six years, at least," he said.

"But when people ask me for advice I always say: 'Have self-belief beyond reason'.

Can Wiggins go as far as 55.25km?

The forecast suggests otherwise. There might not be much weather to deal with in a velodrome but the high-pressure system over London this weekend could cost him as much as a kilometre.

That is just one of the variables that do encroach on the simple purity of the event.

If you are lucky enough to have a ticket for Sunday - they went in seven minutes - you can forget much in the way of pre-ride entertainment: Wiggins will not want you sat down too early stealing his oxygen. And it will be warm, as warm as he can take it.

Under UCI rules, all hour records must be attempted on a velodrome track

"I think he will go warp speed, like Star Trek, between 54-55km," said Voigt.

"And after that not many riders will want to try for a while."

So there is a danger that Sunday could be too much of a good thing, with Britain's greatest cyclist posting one of those once-in-a-generation times, effectively putting the hour back into hibernation.

That would be a shame. But it would also be a wonderful sight.

- Published5 June 2015

- Published4 June 2015

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2016