Tour de France: Why are Team Sky attracting doubters?

- Published

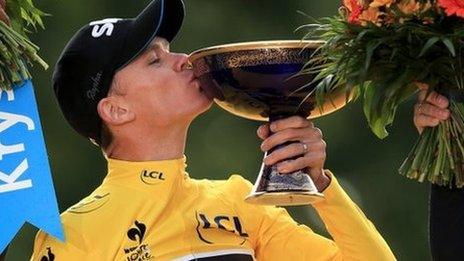

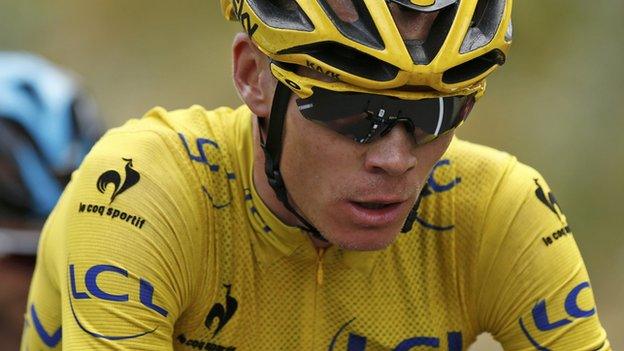

Froome has faced questions and suspicion throughout the entire Tour

Tour de France 2015 | |

|---|---|

Dates: 4-26 July | |

BBC coverage: Live text commentary of every stage online and radio commentary on BBC Radio 5 live sports extra or online from 14:45 BST |

Geraint Thomas is having a magnificent Tour de France.

Sixth overall, despite riding in Chris Froome's service, the 29-year-old Welshman has been a marvel in the mountains, perfect on the pave and a wizard in the wind.

But he is also a double Olympic and triple world champion on the track, with the 4,000m team pursuit his speciality. And that, for some, is a problem.

Michael Rasmussen, the doping Dane who was thrown out of this race while leading in 2007 for lying to his team, is back at the Tour working for a newspaper.

Nothing unusual about that - there are ex-dopers around almost every corner here, working in one part of the Tour circus or another - but the man known as "Chicken Legs" for his skeletal frame, announced his arrival with a tweet during Thursday's 12th stage to Plateau de Beille.

"Geraint Thomas, a track rider, is catching up with a Colombian climber, Nairo Quintana!" wrote Rasmussen, who has confessed to cheating throughout his road career, as Thomas closed down a Quintana attack.

Thomas (second from right) had a successful career on the track, winning Olympic gold

The insinuation was clear. Using the lexicon of suspicion that has become the lingua franca of late, Thomas' ride was "pas normal", a phrase used by Lance Armstrong to describe a performance by a rival that could only have been fuelled by the same drugs he was using.

When asked about this comment on Saturday, Thomas was very angry.

"Guys like Rasmussen know no other way. They are cheats and will always be cheats," the Team Sky rider said.

"What is he even doing here? Why is he given a platform?"

Fair points, all of them, and from a man who always makes himself available to journalists and never ducks a question.

But Thomas has only faced a few polite enquiries when compared with the bad cop/worse cop cross-examinations his team leader Froome has had.

He has been publicly questioned by leading French television and radio pundits Laurent Jalabert and Cedric Vasseur. Jalabert is a sprinter who became a climber and retrospectively tested positive for EPO in 2004 from a 1998 sample, and Vasseur was twice implicated in doping scandals but never convicted.

And French newspapers, from the Tour's paper of record L'Equipe to the big beasts of Le Figaro and Le Monde, have all heaped doubt on the legitimacy of his performances.

Inside Team Sky's travelling kitchen

Froome, at least, should be used to it, having been the subject of one of the loudest whispering campaigns in history thanks to the foghorn effect of social media.

As mentioned last week, some have never believed in his 2011 transformation from peripheral squad member, with no real form and a contract set to expire, to an all-rounder who would have won the Vuelta a Espana had he not been riding in support of Bradley Wiggins.

His performances since have only fuelled the conspiracy theories, and the 2013 Tour champion, external has arguably been scrutinised more than any other sportsman over the past four years.

Some of this is entirely legitimate, given cycling's past and the fact a great many champions have assured us of their propriety only to later be rumbled as cheats - Jalabert and Rasmussen, for example. A degree of scepticism is as sensible at the Tour as travel wash and sunscreen.

This might be frustrating to riders with no connection to the EPO era, but those years made fools of a lot of people, including journalists, and nobody likes that.

It should also be added that Froome and Team Sky have not always helped themselves by occasionally straying from the team's noble founding sentiments, in particular the well-documented "zero tolerance" approach to hiring riders or staff with links to doping, or the promise not to use sick notes for medicine so that riders can race.

"It's not the Wild West" |

|---|

Reporter to Chris Froome on Sunday: "Chris, you have been saying that you're the first, you're in the yellow jersey because you've worked extremely hard for that. We know this but what is troublesome is that all those who preceded you were saying the same. Lance Armstrong would keep telling us that he was the first because he was working more than the others. Can you understand that the wording and the explanation that you give revive bad memories?" |

Froome: "Times have changed, everyone knows that. This isn't the Wild West that it was 10-15 years ago. Of course there are always going to be riders who take risks in this day and age but they are the minority. It was all the other way around 10-15 years ago. There is no reason for that suspicion to continue." |

But, to be fair to Froome, much of this had nothing to do with him.

So we have a situation where an athlete makes a dramatic improvement aged 26, in a sport where cheating was endemic for years and has not been eradicated, and an audience clinging to its faith by its fingertips.

It is hardly surprising the ever-polite Froome has had such a hard time getting everybody to listen to his atypical story: growing up a world away from the sport's heartlands, an initial struggle to adapt to elite racing and a serious bout of bilharzia,, external a chronic disease that can cause flu-like symptoms.

What is surprising, though, is how this cold war, largely confined to the outer territories of Twitter, got so hot again.

Having crashed out of last year's Tour, an in-form and healthy Froome arrived in Utrecht focused on regaining his title. He also had the benefit of the strongest set of riders Team Sky have fielded in their six attempts at this race.

To cap it all, he also had at his disposal the best fleet of vehicles and most attentive set of support staff that Rupert Murdoch's money could buy. Team Sky might not be appreciably richer than the peloton's other big spenders, but they are spending that money very well - you see examples of that almost every day.

Froome's success is in part down to the thorough and efficient preparation of Team Sky

Froome and friends rode a solid first week, but only marginally better than Tejay van Garderen's BMC, before striking what may prove to be the race's decisive blow on the first day in the mountains, when the Kenya-born Briton beat Quintana by 64 seconds.

That, in terms of fresh "evidence" of doping, is it. Everything else - the allegation the power data from Froome's signature victory up Mont Ventoux in 2013 was hacked to the 2012 hiring of a soigneur, or "carer", who used to work for Armstrong's team - has had a very reheated taste to it.

The debate about Froome's 'before/after career', his ungainly style, the absence of one physiological test or another, his asthma, his weight, his heart rate, all of it, does not appear to have moved an inch since 2013, the only respite coming last year when he did not survive the first week.

As Thomas told me on Saturday: "They loved us last year, when we were losing."

This suggests an element of jealousy, a point Ireland's 1987 Tour champion Stephen Roche has also made. The fact a French rider has not won this race for 30 years cannot help.

There is also the underdog factor. In a statesmanlike address on French television on Sunday, the Tour's race director Christian Prudhomme called on fans to "respect the jersey", but reminded us all that dominant riders have rarely been popular.

The French public preferred Raymond Poulidor, the "eternal second", to five-time winner Jacques Anquetil, and Fausto Coppi and Eddy Merckx were both booed at the Tour: Merckx was even punched by a spectator at a pivotal moment in the 1975 Tour.

Angry Geraint Thomas condemns Tour abuse

So as outrageous as the punch thrown at Richie Porte on Tuesday and the cup of urine chucked at Froome on Saturday were, they were not without precedent. Mark Cavendish was doused in the same disgusting fashion two years ago after he was portrayed as the bad guy in a crash with Dutch rider Tom Veelers.

There are an estimated 12 million fans along the route of the Tour every year and some take on a bit too much drink while they wait for the riders. The anarchic free festival at the roadside is both part of cycling's charm and a security nightmare.

But none of this excuses what Froome and his team-mates have had to deal with.

Team Sky's Luke Rowe told me the situation was better during Sunday's stage and he even heard a few cheers of "Allez Sky!" He also said the rest of the peloton had been very supportive.

But I have also heard from team staff about routine shouts of "dopers", and stories of litter thrown at the team's vehicles. Even the approachable Rowe seemed uneasy when other journalists leaned in to hear our conversation.

The truth is whichever team rides as well as Team Sky have at three of the past four editions of this race, will have to deal with comparisons to Armstrong's US Postal squad. That, unfortunately, goes with the territory.

Thomas is sixth in the general classification and enjoying a superb Tour de France

But there is also a lot of added sanctimony on display here, inspired by a combination of jealousy, bruised national pride and staggering hypocrisy.

Team Sky boss Sir Dave Brailsford was asked if he would cease taking his riders to Tenerife's Mount Teide for altitude training - something all of Sky's main rivals now do, too, by the way.

And that, for me, is what underpins a lot - not all, though - of this anti-Sky rhetoric. They have simply stolen a march on the opposition by looking at the demands of the event in the same precise manner British Cycling has tackled the Olympic track programme.

To return to the "transformation" of Thomas from track star to potential Tour contender - a transformation that ignores his impressive road results as a junior - I had a revealing conversation with a former European track champion on Saturday.

I asked about the state of French track cycling and he said: "For the sprints it is great. But in the longer events… pfff, it is all about the Tour."

British cycling, with its funding based on Olympic success, used the track programme to identify and nurture talent for the road: the two disciplines have not been in opposition to each other and there has been a cross-fertilisation of best practice and new ideas.

Has French cycling learned much in the past 30 years? I am not so sure.

- Published13 July 2015

- Published19 July 2015

- Published18 July 2015

- Published17 July 2015

- Published23 July 2015

- Published26 July 2015