Dan Roan asks whether welfare should come before winning

- Published

Varnish and Sutton worked together on the Great Britain track cycling team

It may have started out as a dispute between a track cyclist and her former coach.

But 10 months after Jess Varnish first made allegations of sexism, discrimination and bullying against Shane Sutton - and British Cycling - it is not just the reputation of the country's most successful and best-funded Olympic sport that is on the line.

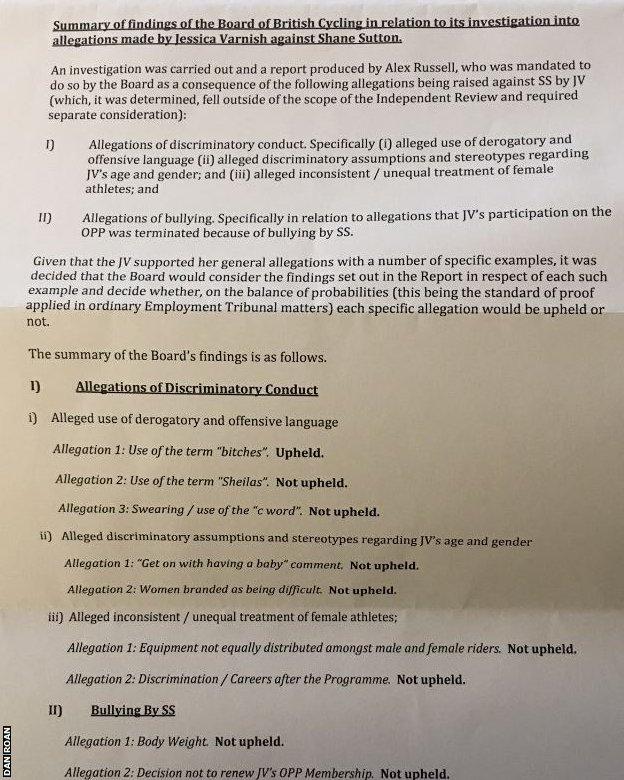

The claims were denied by Sutton, and he was cleared of all but one of nine specific allegations of using discriminatory and inappropriate language by an internal investigation.

But Varnish's portrayal of a "culture of fear" at British Cycling has been backed up by female riders such as Nicole Cooke and Victoria Pendleton, along with para-cyclists and former staff members - triggering an independent review of the culture at its world-class performance programme.

The panel is headed by Annamarie Phelps, chair of British Rowing and is due to publish its findings later this month.

If well-placed sources are to be believed, the much-anticipated report - now delivered to British Cycling's board - could make for grim reading for the governing body.

But it could also raise serious questions for Britain's sporting establishment, the entire approach of funding agency UK Sport, and whether, through its 'no-compromise' approach to the pursuit of medals, standards of behaviour towards elite Olympic and Paralympic athletes are in desperate need of review.

Sprinters blame bosses for Rio miss

Imagine if the report finds evidence that there has indeed been an institutionalised culture of bullying at what was held up as a model governing body. That would seriously raise the stakes for some of British sport's best-respected and most powerful individuals and organisations...

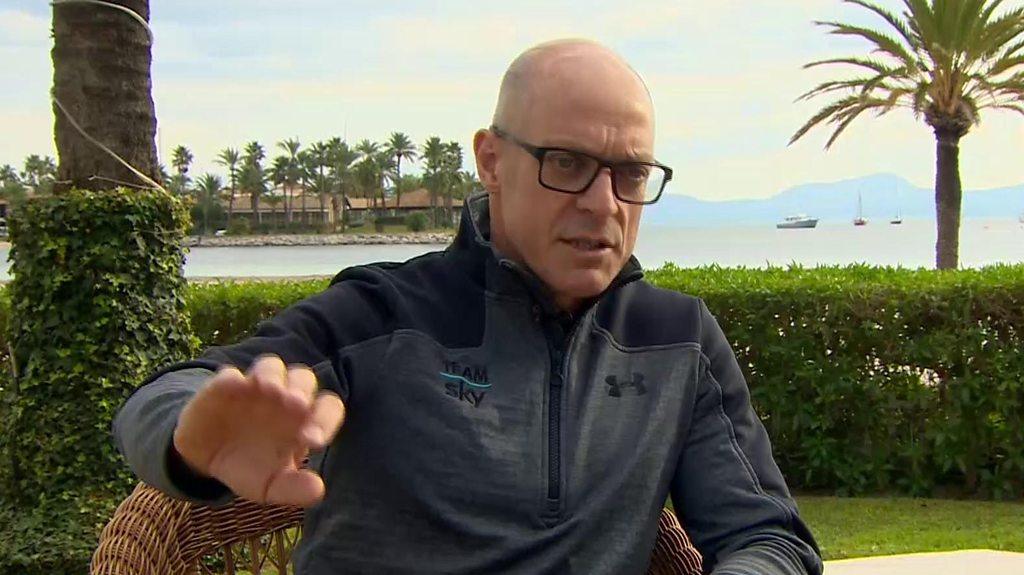

For Team Sky boss Sir Dave Brailsford for instance; a man already under severe pressure over former rider Sir Bradley Wiggins' use of therapeutic use exemptions (TUEs) before major races, and his handling of the furore over the delivery of medication for Wiggins in France in 2011. Performance director at British Cycling from 2007 to 2014, and until recently heralded as the country's leading sports thinker, he denies presiding over any bullying, insisting he was merely uncompromising as he masterminded Team GB's cycling triumphs in successive Games.

For the man who effectively replaced Brailsford at British Cycling, former technical director Shane Sutton, who continues to deny any wrongdoing, and who has plenty of high-profile backers of his own, but who resigned in the wake of Varnish's allegations.

The letter showing British Cycling's findings, obtained by BBC sports editor Dan Roan

For former British Cycling chief executive Ian Drake, who last week stepped down from his position two months early, having announced his resignation last year. He did so amid questions over whether he (and other board members) were aware of claims of bullying and discrimination against Sutton. In 2012 the man he replaced, former chief executive Peter King, took anonymous statements from 40 personnel as part of a report that was never made public. The report may reveal more about this, and examine whether enough was done in the wake of those testimonies. Drake has said he never heard of any complaints relating to Sutton's behaviour in the past.

For Brian Cookson, president of British Cycling for 16 years until 2013, when he became the most powerful man in the sport, elected President of world federation the UCI after campaigning to restore the sport's credibility. At the time Cookson spoke proudly of his time in charge of British Cycling, hailing it a "well-run, stable federation governed on the principles of honesty, transparency and clear divisions of responsibility." A man who, when asked whether he had presided over any bad behaviour, surprised some observers by saying "I don't want to comment on any individual", but then did so anyway, expressing his "great respect" for Sutton.

For British Cycling, which is already under investigation from UK Anti-Doping over allegations of wrongdoing following revelations that one of its former coaches, Simon Cope, delivered that mystery medical package to ex-Team Sky doctor Richard Freeman in 2011. Dr Freeman now works for British Cycling. Both men deny wrongdoing but have been summoned to appear in front of the Commons' Culture, Media and Sport (CMS) Select Committee later this month. The governing body has had to defend its support of women's cycling after a blistering attack by former world road champion Nicole Cooke, who recently told the CMS Committee that British Cycling was "run by men, for men".

For UK Sport, who say they are considering helping fund Cookson's forthcoming UCI re-election campaign this year [they gave him £78,000 to help him get elected in 2013], despite co-commissioning the investigation into the culture of an organisation that he headed up for 16 years. The wisdom of using National Lottery funds to help pay for the election campaigns of British sports administrators has already been questioned. Despite their crucial role in distributing the billions of pounds that have helped bring about Britain's remarkable rise as a sporting superpower in successive Olympic and Paralympic Games, UK Sport's 'no-compromise' approach is already under serious scrutiny after cutting off funding to sports like badminton, table-tennis and wheelchair rugby, whose appeals will be heard later this month.

This whole saga has also shone a light on the contracts and rights of elite-level athletes who are part of performance programmes funded by UK Sport. Varnish believes her contract was not renewed because she had publicly criticised her coaches after her team failed to qualify for the Rio Olympics. Sutton denies this, insisting it was simply down to her performances not being good enough. But regardless of this, and whoever is in the right, some observers are increasingly concerned that the current system is too heavily weighted in favour of the governing bodies. Under the terms of their UK Sport contracts, athletes are not employees, and therefore they lack certain rights afforded to other workers.

Varnish, for instance, amid the devastation of being told she was being axed, claims she was initially given just 48 hours to serve notice whether she wanted to appeal. Often, athletes face that deadline to actually present their case too. And even then, they can only appeal against the process rather than the decision. Athletes who want to challenge selection decisions that determine their livelihoods tend to find their appeals are heard by internal panels made up of officials from the governing body, rather than external, independent arbitrators.

Sutton resigns amid discrimination row

Defenders of the system will argue that in the tough and demanding world of international sport, it has to be this way. Public funding is at stake after all, and coaches like Sutton sometimes have to make tough selection decisions, but do so in order to get results. Staying the right side of the line when it comes to delivering bad news, and the language used, is not always easy. Disappointment is inevitable, and many argue that as long as athletes perform well they are safe - the system is meritocratic. British Cycling also says it extended the appeals process deadline for Varnish.

But it is still easy to see why athletes could feel they are in a vulnerable position. Concerns were heightened last year for instance, after the leak of an email sent by Andy Harrison, British Cycling's technical director, warning riders they could jeopardise their futures by speaking out to the media about the various scandals afflicting the governing body. Harrison later apologised for his "poorly constructed" wording, and British Cycling then said that riders were free to talk to the media without fear, but the damage had been done.

Have governing bodies become too powerful? Does there need to be a greater duty of care towards athletes? More thought given to their lives after their contracts come to an end? Is their an imbalance in the relationship between competitor and coach? Are there cultures of fear at some governing bodies? These are the questions Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson has been wrestling with over the past year. Her government-commissioned review into safety and wellbeing in sport is due to report in the next few weeks.

You may not have heard about it, but in the aftermath of what looks like being an explosive report by Phelps, and the shocking child sex abuse scandal in football, the publication of Grey-Thompson's recommendations could prove highly significant.

No one can deny that the demanding, uncompromising approach adopted by bodies like British Cycling has contributed to medals, and plenty of them. It partly explains how Team GB rose to second place in the Rio medal table. But at what cost?

British Rowing's coaching culture was described on Wednesday as "hard and unrelenting" but cleared of bullying by an internal inquiry. But it also urged more care to be taken of athletes' well-being.

There is a growing sense that the time may have come for British sport to give as much thought to welfare as it does to winning. And in doing so, usher in a new era in the country's sporting evolution.

- Published1 February 2017

- Published30 January 2017

- Published10 January 2017

- Published24 January 2017