Giro d'Italia: Chris Froome in spotlight at start in Jerusalem

- Published

Froome was the first rider to win the Tour-Vuelta double in that order and only the third to win both in the same year

There was once a definitive way that Team Sky rolled up for a Grand Tour: favourite for the winner's jersey, strongest team, best planned preparation, most confident team principal.

With the 101st Giro d'Italia beginning here in Israel on Friday afternoon, much of that superficially seems the same. Chris Froome, winner of the Tour de France and Vuelta a Espana last year, is the dominant stage-racer of his generation.

His lieutenants include three of the men who helped him to yellow in Paris last July and four more ideally suited to the brutal tests ahead. This race has been the team's primary goal for almost six months.

And yet so much is different. The Giro, which sells itself as the world's toughest race in the world's most beautiful place, has always been the Grand Tour least susceptible to Sky's Anglo-Saxon methodology. It goes higher than the Tour and harder than the Vuelta. Its self-made mythology is of solo attacks and poetically flawed heroes rather than the cold application of sports science.

Only once have Sky placed a rider on the podium. Sir Bradley Wiggins, Richie Porte and Geraint Thomas all had obsessively-planned tilts blown away by injury, form or accident.

But the mountains of the Alps, Mount Etna and the vagaries of the May weather in Italy's high country may come as sweet relief over the next three weeks. Froome spent most of his pre-race news conference answering questions about his ongoing anti-doping case.

His team-mates sat alongside him at the top table and were not asked a single question.

Then there is Sir Dave Brailsford, the figurehead of it all, once so bullish, now tetchy at best in the face of public questioning and being pursued in a way that he is clearly struggling to understand.

"I'm constantly thinking about whether I'm the right person to support these riders," says Brailsford

Brailsford had not spoken to the media since a parliamentary Digital Culture Media and Sport select committee said Sky and former star rider Wiggins "crossed an ethical line" by using drugs allowed under anti-doping rules to enhance performance instead of just for medical need.

So it was on Thursday in a ballroom in Jerusalem's Waldorf-Astoria hotel that the questions came at last. Had he considered his own position? Had the select committee's findings triggered changes in the way Sky is being run? Should Froome lose his case after returning an adverse finding for legal asthma drug salbutamol, would he be sacked in line with the team's much vaunted zero-tolerance policy?

It was not what Brailsford wanted to talk about and it was not what the Giro organisers had envisaged when they offered Froome a reported £1.6m to take a tilt at the only Grand Tour absent from his palmares.

Only six men in history have won all three of the big tours. No man has won three in succession since Bernard Hinault in 1982-83. Only Eddie Merckx had pulled it off before then, when he won four a decade earlier, and that in an era when the Vuelta was not the challenge it is today.

This was supposed to the dominant narrative of the 101st Giro: history made at its grande partenza as the first time a Grand Tour has started outside Europe; history in sight as the race snaked from Sicily to the mountains of the north and then on to Rome.

Froome has won four Tour de France titles in the last five years

It may still happen. Froome insists the dark clouds over his reputation have not affected his preparation. He told BBC Sport that he expects to be cleared. He said that there had been no sleepless nights.

The four-time Tour champion has always possessed the mild air of an accountant away from his bike and the ruthless manner of a killer in the saddle. He is a rider who has reached the summit via the most unlikely of paths and who has shown that ability to tuck away troubles and focus on the fight at hand that marks out many great champions.

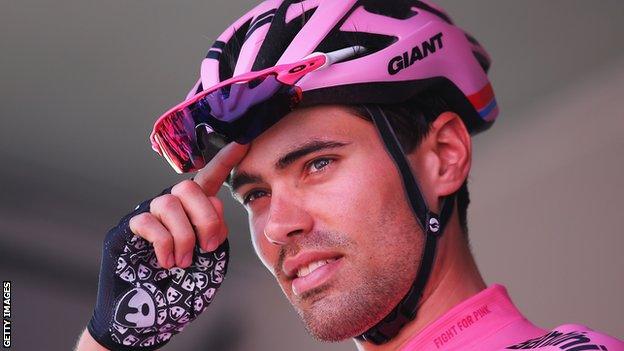

His team is stronger than that of Tom Dumoulin, the Dutchman who won the maglia rosa in such dramatic fashion a year ago with Team Sunweb. He proved himself superior to Italy's Fabio Aru when the pair duelled in France last summer. He has drawn rich dividends from his natural talent in a way that France's Thibaut Pinot and Colombia's Esteban Chaves have not yet managed.

Dumoulin sealed his comeback victory 11 months back with a dominant time trial performance on the penultimate stage. The world time trial champion will hope to put a little time into his rivals on the opening 9.7km solo stage and a lot more on the rolling 34.5km time trial of stage 16.

Defending champion Tom Dumoulin on Froome's anti-doping case: "if I would be in same situation, I would not be here."

But Froome, third behind Dumoulin at those Worlds last September, can time-trial like a champion, and when the roads head up can live with the climbers like Chaves too. Stage 14 takes on the infamous Zoncolan, with its 10.1km of climbing averaging almost 12%, while stage 19 tops out at 2,178m on the Colle delle Finestre's nine kilometres of dirt road.

It is there that Froome's race is likely to be decided, and there that his team's ability to support him like no other could prove critical once more.

By then Sky and race organisers RCS will hope the attention is all on the roads and racing rather than the politics of sport and its starting place.

The Giro is the largest international sporting event that Israel has hosted, and in a region beset by seemingly intractable conflict that means the wider context has been impossible to ignore here in Jerusalem.

You pay to host a race like this, with the Israeli government and billionaire Sylvan Adams rumoured to have spent £14m to bring these first three days of racing to the country.

Adams also runs the Israeli Cycling Academy, one of the four teams granted a wildcard into the race, and in Guy Niv and Guy Sagiv the nation will now have the first Grand Tour riders in its history. A velodrome is being built in Jerusalem and much made of the wider cycling legacy that will be created.

Follow the BBC's daily live text commentary of the Giro d'Italia on the BBC Sport website

Others see little more than a concerted effort to present an image of Israel to the world at odds with the reality. Amnesty International has accused Israel of trying to "sportwash" its reputation, as protests continue in the Gaza Strip that have so far led to the death of 35 Palestinian protestors.

Professional sports are adept at navel-gazing. All that can appear to matter is the competition and those who succeed in it.

This Giro may end that way. But it begins as more than a bike race, no matter how hard some may try to pretend otherwise.

Analysis

Yolande Knell, BBC Middle East correspondent, Jerusalem

The Canadian-Israeli cycling enthusiast credited with bringing this prestigious sporting event to Israel, Sylvan Adams, sees it as great PR - a chance to show the country as safe and "normal" rather than associating it with war and conflict.

But that's an idea that angered Palestinians who were further disappointed that two teams with Arab ownership decided to take part.

Human rights groups tried - and failed - to lobby the Giro owners to rethink the location of the 'Big Start' accusing Israel of "escalating violations of international law".

The race course carefully avoids East Jerusalem and its Old City - which the international community considers occupied territory - but when the Giro billed the opening leg as in "West Jerusalem" it only stirred up controversy.

Israel - which sees the entire city as its undivided capital - complained and the location was changed to "Jerusalem". That in turn, raised objections from the Palestinians who said it served to "legitimise the annexation of Jerusalem.

- Published27 May 2018

- Published2 May 2018

- Published2 May 2018