Chris Froome: Team Sky's unprecedented release of data reveals how British rider won Giro d'Italia

- Published

Team Sky have taken the unprecedented step of releasing a cache of data to BBC Sport detailing Chris Froome's diet, power output and heart-rate from the Briton's victory in May's Giro d'Italia.

On Monday, an anti-doping case against Froome was dropped by the UCI, cycling's world governing body, following an investigation after more than the allowed level of legal asthma drug salbutamol was found in his urine during his Vuelta a Espana triumph in September 2017.

"I'm happy to share data to back up some of the performances we have done out on the roads," four-time Tour de France champion Froome told BBC Sport.

Team Sky told the BBC that Froome used salbutamol during the Giro to manage his asthma. He neither applied for nor used any therapeutic use exemptions (TUE). Salbutamol, used through an inhaler, does not require a TUE.

The British-based outfit have gone through two years in which their reputation has been repeatedly questioned, with the Sir Bradley Wiggins TUE revelations and the 'jiffy bag' scandal part of it, but they accepted mistakes have been made and say they want to be more transparent.

Now the BBC can shine further light on Froome's latest Grand Tour victory, which was based on a spectacular solo break on stage 19.

We assembled three experts to examine this data, given to the BBC in June.

Former professional rider Rob Hayles says he does not think other teams are being this "precise". Cycling author Michael Hutchinson suggests what Team Sky were trying to achieve was "a very fine balance". And cycling journalist Jeremy Whittle says the release "would not make any difference to the doubters".

There is also a link to each document in full, so you can examine each yourself, listen to the accompanying podcast, and draw your own conclusions.

The plan

What is it?

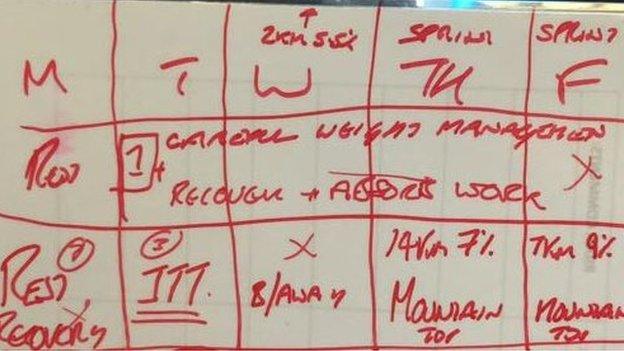

Team Sky principal Sir Dave Brailsford's hand-drawn training plan and a more precise version covering the last two weeks of the Giro, revealing they wanted Froome to lose weight.

What does it show?

Michael Hutchinson: They're trying to make Froome a kilo or two lighter for those key mountain stages. This is an extension of Sky's training camps - combining hard training with weight loss. It's a difficult thing to balance. Sky are trying to run a specific calorific deficit each day, like dieting, but combining it with riding 200km races. It's a fine balance.

What does it mean?

Rob Hayles: Is it normal to deliberately lose weight across a Grand Tour? No. Are you able to do it clean? Yes. It would have to be done to a stringent protocol, because if you don't eat enough under the duress of a three-week stage race it would be easy to tip the balance - to under fuel - which is what I think [long-time leader of the race] Simon Yates did. Get it wrong and it goes pear-shaped quickly. You can lose power and energy, and it's a long way to get that back.

Michael Hutchinson: It shouldn't be hard to lose weight, looking at energy expenditure, but the difficult thing is to keep recovering and managing the fuelling issue. The later you can get to race weight the better. If you can hit it just before the crucial mountain stage then that's ideal. But it feels scary to be balancing it on the last two weeks of the Giro.

Jeremy Whittle: Weight loss to the point when you're on a razor's edge between ill-health and sustainable health for a Grand Tour has been going on for a long time. When Bradley Wiggins won the Tour de France in 2012 he described it as like screwing a screw into a tile. One turn too many and the whole thing shatters.

The fuel

What is it?

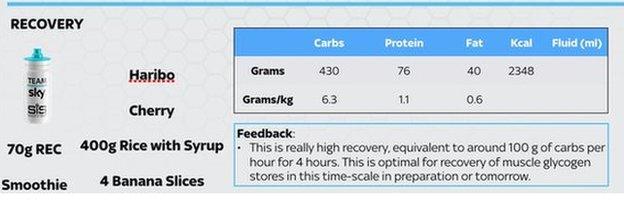

Froome's daily nutritional analysis for stages 11 and 19, revealing what and when he ate and drank, with its nutritional value. The BBC has been shown the details for each of the 21 stages. These two stages have been selected because stage 19 was the decisive one and 11 provides comparison from a less punishing day.

What does it show?

Michael Hutchinson: What's interesting is the contrast between dinner for stage 11, which adds up to 445 calories, and dinner on stage 19, which is almost 1,000 calories. By stage 18, rather than running a deficit, Froome is eating what he expends. He's not looking to lose weight any more. He's taking on massive amounts of carbohydrate. On stage 19 he ate 1.3kg of carbs - enough calories for four men to get through an ordinary day. Even his recovery snack contains 2,500 calories, which is enough for a man for one day - and eaten in 20 minutes after the stage has finished.

Rob Hayles: It's not Come Dine With Me. It's fuel for a specific job. We know Sky have made shocking mistakes in some areas. But this is so precise. I knew how big my meal was and I made sure I had carbs and protein in there, but never had a clue of the detailed make-up.

What does it mean?

Jeremy Whittle: This illustrates the depth of personnel and resources Sky have compared to other teams. They have a significant enough budget that they can have a full-time nutritionist and a chef. Most teams have a chef, but Sky physically have more people on the ground who can do more of the detailed stuff.

The plot

What is it?

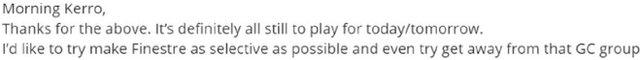

Froome and his coach Tim Kerrison exchange messages before stage 19.

Froome's coach Tim Kerrison was at a Sky training camp on Tenerife during the Giro. Kerrison messaged Froome late on the evening before stage 19 telling him "there is still much more of this race to play out" and "nothing is impossible".

Froome replied on the morning of stage, saying he'd "like to try to make Finestre as selective as possible and even try get away from that GC (General Classification) group".

The stats

What is it?

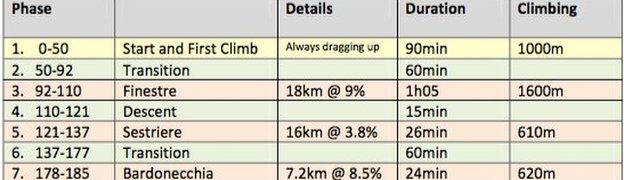

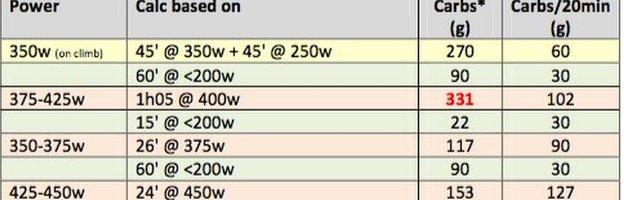

Team Sky's energy expenditure and fuelling plan for Froome, written before stage 19.

What does it show?

Michael Hutchinson: They have broken the stage into sections and worked out the average power they expect to see from Chris, and how much energy they expect him to burn. They can then work out the total carbohydrate reserve they expect Froome to start each section with, and the amount of extra carbohydrate he can take on. They are balancing energy in and energy out. They've done the maths with the aim of getting Froome to the top of the final climb perfectly exhausted. It's another classic Sky spreadsheet: they've worked out how you cover the last 80km of this stage as fast and efficiently as possible.

What does it mean?

Rob Hayles: I don't think other teams are doing this. The next most important racer to Froome that day was the leader, Tom Dumoulin. His team Sunweb didn't do this. On the start line, Froome knew exactly what he and his team were going to do. You still have to deliver it. The other teams were all put on the back foot.

The detail

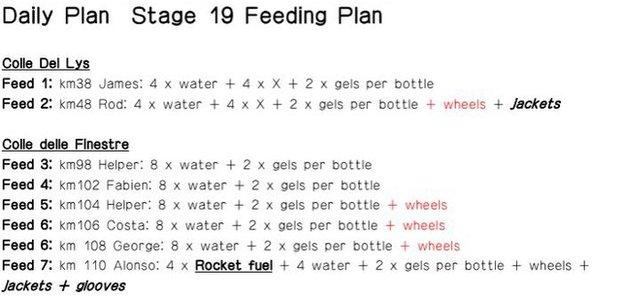

What is it?

A plan showing how many feed stations Team Sky had on the 19th stage, where exactly each one was and what they had with them - including a drink called 'Rocket Fuel'.

What does it show?

Rob Hayles: They had people all over the route.

Michael Hutchinson: Every two kilometres up the Finestre they had a helper. They had six on that climb, all with bottles, gels and wheels.

What does it mean?

Jeremy Whittle: This is not just about Froome's physical capacity. It is about his mental capacity and resilience. He has to understand this detail to allow him to achieve that objective. You could put that in front of other riders who aren't as versed in sports science, and they might not understand the detail. I've been critical of Sky, external and Froome but whatever else you think, it's a good marriage of intelligence and athletic ambition.

Team Sky nutritionist James Morton: The real name for Rocket Fuel is Beta Fuel. It's multiple-source carbohydrate drink. It contains a mixture of maltodextrin and fructose. That science has been around for a long time. What makes it different is the quantity of carbohydrate. Most sports drinks contain roughly 20-40g of carbohydrate. This contains 80g.

Michael Hutchinson: The way they put this stage together depends entirely on how much fuel they can get in their athlete. Because there's a limited amount of carbs you can get in, you have to get it in as fast as possible.

Jeremy Whittle: There may be other teams using these drinks. I don't doubt the meticulous nature of what Sky are doing. How radical it is compared to other WorldTour teams with similar budgets, I'm not sure.

The analysis

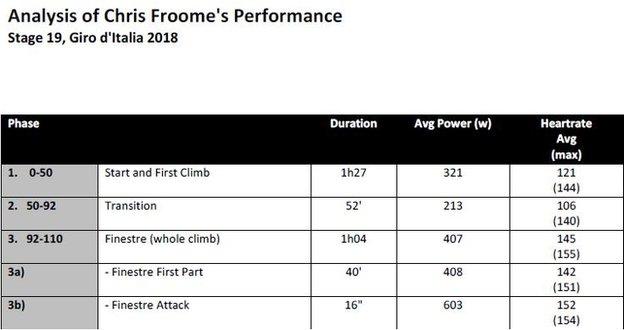

What is it?

This data was requested by the BBC and collated by Froome's coach Kerrison. It shows power, heart-rate, cadence and other data for Froome across the whole of stage 19, including where time was made up on race leader Tom Dumoulin. All other documents are internal Sky communications.

What does it show?

Michael Hutchinson: There is nothing that would make you suspicious. It matches reasonably closely the plan they made. For an aerobic athlete like Froome, 603 watts on Finestre is a hard effort - if he was going for one final sprint at the end of the stage he could perhaps go up to 800. It's a measured effort, designed to work off energy consumption they had given him. As headline numbers, you're not thinking: 'How does any human do that?'

Tim Kerrison: His maximum heart-rate was on the final climb - 159. His resting heart-rate that morning was 32, or one beat every two seconds. He has a remarkably low heart-rate but it's the same for a lot of elite athletes.

What does it mean?

Michael Hutchinson: The problem with this kind of data is that while it is very nice and we assume it's accurate, it needs context to make sense of it. It makes perfect internal sense. You need external data. If we knew the power output of every rider in that lead group over the hills towards the end of this stage, if there was anything that didn't match we'd spot it.

Jeremy Whittle: I don't think this will make a difference to the doubters. The problem is Sky are having to release this because of the failure of anti-doping. We, as the public, no longer believe anti-doping measures are effective enough, that we can trust them - and that's not just in cycling.

This doesn't prove anything in terms of propriety or implausibility either. It contributes to our wealth of knowledge. People who believe in Froome will seize it as evidence that he's completely credible. People who disbelieve in Froome will point to the information we don't have.