Cycling & suffering - a special relationship

- Published

- comments

Bobridge retired at the age of 27 because of rheumatoid arthritis

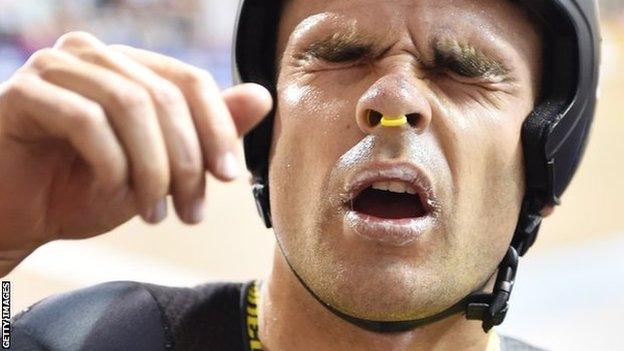

Jack Bobridge said it felt like "the closest you could come to death without actually dying".

An Australian ex-professional road racer and Olympic track medallist, in 2015 he attempted to set a new world record for distance cycled in one hour.

It took him to the brink of total exhaustion.

Crumpled over his handlebars after coming to a stop, mouth hanging open and eyes twisted tightly shut, he struggled to stay on his feet and had to be helped into a plastic chair, where his body continued to throb and howl.

In cycling it is often said that the rider who suffers longest, wins. The losers suffer plenty too.

Bobridge fell about 500m short of breaking the hour record. But he came close because he pushed his body far further than many would think possible, through sheer will.

Cycling is full of such examples. It is a sport that holds a special place of admiration for those who can endure extreme hardship, even those entangled in its dark doping past. Frostbite in the spring Classics, Geraint Thomas' broken pelvis and the death of Tom Simpson.

Here, three riders of the modern age share insight into suffering on the bike.

How do they cope with it? Where does the motivation come from? And how might advances in neuroscience and physiology affect this relationship in the future?

Jens Voigt broke the world hour record in September 2014, riding 51.110km

"Now I am OK, but for some time I was actually happy to have the pain because I could release my demons in the right way," Jens Voigt says.

"Often people asked me what I would do without cycling, and I would say I'd be like the main character in Grand Theft Auto. Too much anger and too much energy.

"I was glad to have it because I could put myself into pain, I could hurt others, and I got paid for it. I even got applause."

Now retired and living with his wife and six children in Berlin, German Voigt, 47, is looking back on his career as an incredibly aggressive professional cyclist.

He was a breakaway specialist, a hardworking team member who always fought to the end, a cult figure admired for his audacity and charisma. You may have heard his catchphrase: "Shut up legs!"

Voigt believes his capacity to suffer - perhaps even why he relished doing so - stems from his childhood in communist East Germany.

"My young life was basically built around discipline and resilience," he says.

"I wouldn't say my life was terrible - far from it - but things didn't come easy to me.

"We were a poor family and my dad, who is turning 73 this year, was a blacksmith.

"He worked hard. He was pretty beaten by life. He has had one knee replaced, one hip replaced.

"He lost half a finger during work. He would do overhead welding and the molten metal would drip down into the sleeves of his work clothes, he still has burn marks.

"I remember when I was nine or 10, we went on a trip with my parents to the zoo and, just like any other kid in the world, I was saying, 'Dad, I'm thirsty. Dad, I'm tired. Dad, my legs are hurting.'

"My dad said, 'Son, the mind has to control the body, not the other way around.'

"That's where 'Shut up legs' started!"

Like Bobridge, Voigt was one of several riders to take aim at the hour record following a May 2014 rule change brought fresh appeal.

Voigt set the first record of that new era, at the age of 42 in September 2014, before immediately retiring from the sport.

Part of his strategy was to distract his mind from the full extent of the intimidating challenge, breaking it down into 20-minute efforts.

During road races, he would employ the same tactic - tricking himself into "hanging on longer than I thought I could" by setting short immediate goals to reach. The next tree, the next half mile, the next signpost, one more lap. Then repeat the technique again and again.

But there comes a point when that strategy must run dry. So what happens when you still push yourself to go beyond?

"You are almost in a trance. You don't take in anything of what's around you," Voigt says.

"The wheel in front is just a blur, the sounds of the crowd cut out. You just shut down everything to save energy - it all goes.

"You don't reach that very often. Those are some special moments.

"After you go through so much suffering and you finish with the first group, you are proud; your body flows with happy hormones. I was a bit of an endorphin junkie.

"That was my drugs, my motivation. The moment when it's all over, the pain goes down and you are so proud and happy. Those were the moments that kept me motivated to go through all the pain.

"It still feels good to sweat, to go through a bit of pain, have a shower and feel like a completely new person. Like you've squeezed every bad chemical out of your body, you feel clean and whole. I still like that."

Voigt has told his kids to "shoot me in the knee if they ever hear me say the word 'comeback'".

But he takes his mountain bike off road, he enjoys running, and he still has an emotional connection with cycling. He even has a "secret hero" - Australian rider Adam Hansen.

Voigt describes Hansen as "very smart, softly spoken, an intelligent person with great humour".

He adds: "If I was younger I would have his poster on my wall. He is a tough cookie."

Lotto-Soudal rider Hansen holds the record for competing in the most consecutive Grand Tours, cycling's biggest stage races - the Giro d'Italia, Tour de France and Vuelta a Espana. Three weeks of fierce mental and physical effort each one.

His 20th in a row came at last year's Giro.

Hansen has established a reputation in the sport for his ability to endure pain and extreme exhaustion. He rode through the 2013 Giro with a broken sternum.

Now 37, he is relaxed and generous company during a phone conversation from his home in Czech Republic, where he manufactures his own carbon fibre racing shoes.

Hansen's resilience seems to run from a very different source to the "high testosterone" reserves of anger described by Voigt.

He says: "I think I'm the most relaxed, calm person there is. When something goes wrong I never stress or panic and I never lose my temper. It even annoys people.

"Maybe it's related to the hard racing and the suffering, I don't know.

"I had no idea how much suffering was involved in cycling - it's a totally different aspect to other sports. To me, it is more a mental game than a physical game.

"When you're on the bike pushing yourself you have to constantly fight against your conscience. You're totally having an argument the whole time.

"A bad sleep, the wrong food not digested properly - all these things magically come up in the race when you are at your limit, and you have to fight them with different arguments.

"And at the Tour, Giro or Vuelta all the many outside pressures really mean you have to push yourself over your limit, every stage.

"You bring up all the reasons in the world as to why you have to continue, while your brain is telling you all the reasons why you have to stop."

The human brain is an extremely mysterious thing.

Take the anterior cingulate cortex. This is the part of the brain identified as being involved in the perception of effort. It is also involved in the solving of moral dilemmas, focusing attention and empathy.

There is a technique called trans-cranial direct current stimulation (TDCS) which, when used to target this area of the brain, has the effect of reducing perception of effort, effectively expanding the limits of physical exhaustion.

It involves very low frequency electric currents being passed over the skull and is also employed in the treatment of depression, epilepsy, stroke, dementia and mental illness.

Experiments - many of which involve cycling as a test of endurance - have shown that athletes can perform harder for longer after it is administered.

A commercially available product made by an American company for the sport market looks like a set of headphones. Portable, cheap, and easily administered.

Several American professional sports teams have incorporated it into their training, and Team Sky boss Sir Dave Brailsford has tried it out., external

Dr Walter Staiano says the idea of "hacking the brain to go beyond what we think of as our physical limits" has become "a hot topic in the past 10 years".

"I think it will explode after Tokyo 2020," he adds.

Staiano is an Italian neuroperformance consultant from the University of Valencia who has worked with elite sporting bodies in Denmark and Australia.

He has collaborated with Professor Samuele Marcora, external of the University of Kent, a leading researcher into the mind's role in endurance performance.

Marcora's 'psychobiological model' states that in practical terms the mind fundamentally plays the biggest part in limiting our ability to maintain high levels of intense effort.

Oxygen delivery to the muscles, glycogen levels, correct body temperature - these all play large roles but are not considered to be wholly decisive factors.

Cognitive training involving intense, repetitive and dull mental exercise, TDCS, motivational self-talk and bombarding the senses with subliminal positive messages have all been found to boost the mind's ability to resist fatigue, in Marcora and Staiano's research.

There are simpler, more traditional ways to increase stamina, such as intensive physical training, targeted nutrition and correct practice in recovery.

But Staiano says: "Athletes who are already maxed out in their physical training can turn to these new areas of gains. It's becoming more and more relevant."

Still, one facet of the mind's power to compel the body on is difficult to fully understand in laboratory conditions: the transformative thrill of success.

British cyclist Alex Dowsett, a time-trial specialist with Katusha Alpecin, did break the hour record, four months after Bobridge's failed attempt.

He rode 52.937km in Manchester's velodrome in May 2015, a total bettered by Sir Bradley Wiggins a month later. Wiggins' 54.526km remains the mark to beat.

Like Voigt and Hansen, Dowsett often uses what Marcora describes as motivational self-talk naturally, without necessarily thinking to.

But Dowsett says the most powerful message does not come from within.

It instead comes from the team car, the race update that brings everything together, a year's worth of early morning training starts in one moment of clarity.

"I've found in the past if I'm told I'm being beaten significantly then I just get worse because I know there is no hope of pulling it back. I'm just suffering for nothing," Dowsett says.

"The best message I ever get is: you're winning this and winning significantly.

"It's one of the best feelings in the world and the suffering and pain just seem to disappear. Then I find it very easy to go much, much harder. That comes from a euphoric kind of place.

"I feel like we all suffer probably within about 5-10% of each other, and the rest just comes down to talent.

"But the pain and effort, everything's for an end goal.

"I know the rewards for suffering. I do all this to win bike races."

Alex Dowsett's record-breaking hour ride stood for just over a month before Bradley Wiggins broke it in June 2015

Adam Hansen (centre) celebrated his 20th consecutive Grand Tour when he completed the 2018 Giro d'Italia

Luis Ocana, Eddy Merckx and Raymond Poulidor climb up Mont Ventoux in the 1972 Tour de France

Briton Tom Simpson collapsed through exhaustion and died while climbing Mont Ventoux in the 1967 Tour

Bradley Wiggins' hour record of 54.526km remains the distance to beat. There have been nine failed attempts since

Geraint Thomas (right) rode much of the 2013 Tour de France with a broken pelvis, in the service of Chris Froome. Five years on Thomas would win the yellow jersey himself