Sir Alex Ferguson: Man Utd reign puts him among sporting greats

- Published

- comments

If the timing and manner of Sir Alex Ferguson's leaving was unexpected - a single sentence on Twitter, a phenomenon he could never have imagined and being read on devices his generation only dreamt of - the reaction to it could go just one way.

Whichever way you choose to define sporting greatness, Ferguson - across almost 1,500 games at Manchester United and plenty more before his migration south - has constructed a case as incontestable as any coach in world sport.

At the end of a reign as sustained and successful as his, it can be easy to forget how hard-won the initial victories were, how unlikely the domination that followed.

Ferguson may have out-lasted prime ministers, popes and dictators while combining the charisma, drive and zeal of all three, but on 6 November 1986, his new club two decades without a league title,, external success of any sort required a seismic change.

If the country at large was an unrecognisable place from now (a mobile phone was one with a long cord, a tablet something you took for high blood pressure), so too was football. On that autumn day, three of the bottom four places in the First Division table were filled by Manchester United, Manchester City and Chelsea.

Everton would be champions, Liverpool were the dominant force. Oxford, Luton, Wimbledon and Coventry all sat comfortably above United in that league table.

Establishing United as champions in that landscape was an achievement many thought impossible. But it was in maintaining that success over the subsequent years that explains why Ferguson will retire with the epitaph of his country's greatest ever manager.

There are the numbers: 1,498 games in charge, only 267 defeats; 527 Premier League games won - at least 161 more than any other manager; 13 league titles, five FA Cups, four League Cups and two Champions Leagues. When he took the job 9,680 days ago, 17 players in United's current squad had not even been born; by the time he left 1,146 other managers had been and gone from the top four divisions.

There are the immediate challengers seen off, the rivals who dared take away titles only to be subsequently overtaken themselves: Leeds, Blackburn, Arsenal, Chelsea, Manchester City.

There is the consistency (in the last 22 seasons, United have never finished outside the top three and only three times outside top two), and then there is the constant revolution. By most pundits' reckoning, Ferguson has now built six distinct teams, all of them championship winners.

It is a dominance with precious few parallels in modern sport. Empires come and go, some lasting longer than others, but all of them crumbling even as Ferguson was rebuilding again and again.

In the time he has been at Old Trafford, cricket has seen the hegemonies of the West Indies and Australia arrive and depart, Formula 1 the rise and fall of Williams, McLaren and Ferrari; rugby union four different champions in four World Cups.

Archive: Ferguson embarks on Man Utd journey in 1986

Other great managers have dominated British football. Herbert Chapman took an unfancied Huddersfield side to three successive top-flight league titles before repeating that feat with Arsenal. Bill Shankly rebuilt a club over 16 years, winning three league titles and two FA Cups before Bob Paisley extended the Liverpool empire with six league titles in nine years and three European Cups.

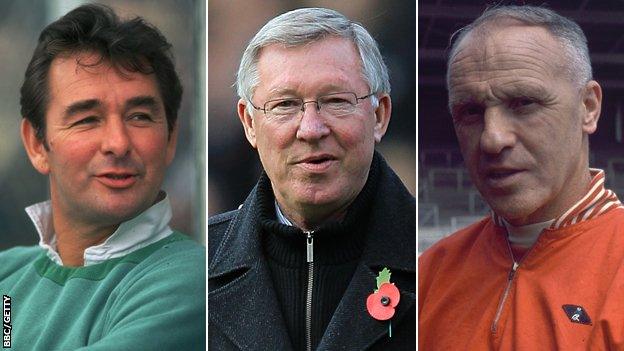

Sir Matt Busby preceded Sir Alex with 24 years, five league titles, two FA Cups and a European Cup. Brian Clough's two European Cups at Nottingham Forest appear more alchemic with every passing year, while north of the border, Jock Stein not only guided Celtic to that remarkable nine successive Scottish League championships but also made them the first British side to lift the European Cup.

Ferguson first matched their achievements and then surpassed them. "He never feels like he's got to the top of the mountain," explained former United stalwart Gary Neville. "He always feels he has to go further and higher."

What of coaches from outside these isles?

Real Madrid's legendary Miguel Munoz won nine La Liga titles, two Copa del Reys and the European Cup twice during his 14-year reign from 1960. In just 11 years Ferguson's great rival Jose Mourinho has bagged seven league titles in four different countries and two Champions Leagues; Pep Guardiola, another man who is surely not finished, has the same European successes and three Spanish titles.

These are titans of the game, magicians of the managerial world. Ferguson's statistics transcend theirs all the same.

Outside football, only a few stellar names rank alongside. There is Green Bay's own era-builder, Vince Lombardi, with his five NFL league titles in seven years, and ice hockey's Scotty Bowman, who won nine Stanley Cups with three different teams across 29 years.

There is zen master Phil Jackson, as calm as Fergie could be furious, winner of six NBA titles over nine years with the Chicago Bulls and five in 10 years with the LA Lakers, a man who too could rebuild teams repeatedly and bring the best from legends and toilers alike. Britain's own cycling sorcerer, Dave Brailsford, has also achieved what was thought to be impossible.

Ferguson's triumphs were certainly aided by cash. Outside the big-budget interregnums of Jack Walker, Roman Abramovich and Sheikh Mansour, he was backed with the sort of money that few of his rivals could match, ensuring that the most expensive names could be brought to United throughout his reign. But he also discovered diamonds, rough-cut or ready-polished. Peter Schmeichel, Eric Cantona and Ole Gunnar Solskjaer all cost less than contemporaries like Dave Beasant, Chris Kiwomya and Brian Deane.

He was given time. It took him five and a half years to secure that precious first league title, an indulgence that few managers today could expect. In December 1989, after six defeats in eight games and an infamous 5-1 thrashing from arch-rivals City, execution was stayed when many would have been for the chop.

Critically, he used the time to overhaul the entire ethos and culture of the club, to develop a youth system that would bear unprecedented fruit.

When the time came to move players on, Ferguson knew even before they did, perhaps only Jaap Stam of his big names sold too soon. As the game changed, the ageing man changed with it as his rivals - George Graham, Kenny Dalglish, Arsene Wenger - perhaps could not.

Ferguson - Britain's most successful manager

Many of those who most love Ferguson will struggle to imagine Manchester United without him, in part because many of them will never have experienced it. It is the footballing equivalent of the fall of the Berlin Wall: you knew it was inevitable at some stage, but when it happens few can believe it.

Even those who hate him, or have seen their own team's hopes wrecked by his relentless quest for supremacy, have had their supporting lives defined by his achievements.

He has given phrases to the dictionary - Fergie Time, the hairdryer treatment, squeaky-bum time.

More than that, he has become one of Britain's most recognised sporting figures across the globe - a birthday guest of Nelson Mandela, feted by youthful idols like Usain Bolt, Rafa Nadal and Rory McIlroy as news of his departure spread.

Nadal was just five months old when Ferguson was appointed Manchester United manager, Bolt three months. McIlroy would not arrive for another three years. Ferguson's own iconic status meant that they paid homage nonetheless.

No other manager could conceivably have drawn such tributes, just as only the most loyal or loved have also been awarded knighthoods. Walter Winterbottom, Alf Ramsey and Bobby Robson all have their indisputable place in football history, yet Ferguson's impact on the game was possibly - respectfully - greater than all.

When great dynasties come to an end, there is always fear of what might follow. Ferguson has come to define his club's timeless image, even as its true nature has been transformed under the Glazers' predatory ownership.

With chief executive David Gill also on his way, Rio Ferdinand out of contract, Ryan Giggs approaching his 40th birthday and Wayne Rooney repeatedly rumoured to be heading overseas, this may be the end of an era in more ways than one.

For those who have been part of it, there will be both a celebration of what was achieved and a certain sadness that it is, at last, no more.

- Published8 May 2013

- Published9 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Published9 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Attribution

- Published8 May 2013