David Moyes: Powerless to prevent the death of his dream

- Published

There are some leaders who can successfully hide their disappointment and difficulty, presenting to the world an exterior carved from granite even if it is all black self-doubt and fear on the inside.

Then there are those, like David Moyes, for whom every gesture and expression spells it out: I am in trouble, I am sinking, I am lost.

There is something of the classical tragedy about the rise and fall of Moyes as Manchester United manager: a man finally achieving his greatest ambition, only to find himself powerless as it first sours and then destroys both his present and his future.

A spectator dressed as the Grim Reaper taunted Moyes in his last game in charge of Manchester United

Yet even doomed Greek heroes never had to cope with light aircraft flying overhead towing insulting banners, bookmakers sponsoring scythe-wielding Grim Reapers and death by casual tweet.

When we are presented with an almighty challenge, we all hope we can rise to it, even as we are daunted by the size of the task ahead.

Instead, Moyes, who was convinced he had the ability and resolve to succeed at Old Trafford even as he understood the near-impossibility of following the club's greatest ever manager with one of its weakest squads, has seen his defining ambition end in total humiliation.

Moyes looked increasingly haunted as United's season went from bad to worse

Frank O'Farrell, who lasted eight more months as United manager in similar circumstances, had a chapter in his autobiography entitled 'A Nice Day for an Execution'. At least O'Farrell was told face to face, even if Sir Matt Busby could not make eye contact.

For Moyes, there was a tortured day of swinging in the noose as the sporting world discussed his end like an open secret.

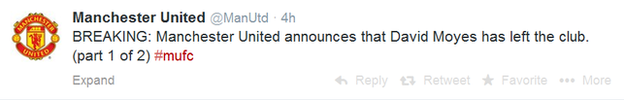

Then, on a typically downbeat damp morning in Manchester, came a 32-word tweet from a club that once considered itself above the grubby manoeuvrings of lesser football institutions.

The first part of United's tweet confirming the sacking of David Moyes

Managers expect potholes and speed-bumps when they set out on long journeys. Moyes found himself both confronted by problems he could anticipate and ambushed by those he couldn't.

On his first day at Everton, he had walked into their Bellefield training ground to be confronted by the sight of Paul Gascoigne, Duncan Ferguson and David Ginola.

Having succeeded in dealing with such ageing and disillusioned stars in his inexperienced past, he believed he could do the same at United.

He was wrong. Hanging on for a summer rebuild, waiting for the moment to build his own team, he could not keep the old guard with him long enough to get the chance.

Footballers care about status. Sir Alex Ferguson's was untouchable. Moyes, trophyless at Goodison Park, his Champions League experience limited to a single brief encounter in one qualifying round, found the questions were as simple as they were cutting.

"Who are you and what have you achieved?"

Moyes never won a trophy at Everton - Giggs has won every domestic honour going

Every day the doubt. Every day the knives.

Cushioned by the illusion of time created by his six-year contract, he thought he could convince some of those cynics and outlast the others.

Instead, those problems multiplied, at first slowly and then exponentially. Where quick, big decisions were required, he thought of the long-term. Where Everton had bent to his will, United's old power structure pushed back. Players complained. Agents talked. Authority leached away.

When we find ourselves in a tailspin, we fall back on what we know. Moyes has always been defined by his unstinting hard work and attention to detail. Get in earlier, work them longer, plan and plan and plan.

The panic when those old dependables failed was visible for all to see: on the touchline, head buried in hands or wide eyes staring up at the Manchester skies; in post-match interviews, melancholy and helpless.

Moyes was at a loss to explain Manchester United's troubles

Moyes is an honest man. In most walks of life, that would be considered a valuable characteristic. As his death-dive accelerated, it instead became a weight around his ankles.

He was probably right when he said that Manchester City were the new benchmark, or that Liverpool were favourites before their 3-0 win a few months ago. But Ferguson would never have admitted such weakness in public, just as he would never have countenanced such open revolt from his star names.

Moyes is also instinctively cautious. His response to each defeat was to retreat further into that caution, setting out not to lose, seeking to protect what he had. It was both the antithesis of the Ferguson way and the opposite of what his disgruntled supporters demanded.

He had surrounded himself with loyal lieutenants from his Everton bootroom, reasoning that they would offer more support than the remnants of the old regime. Instead, he appeared more alone than ever, shorn of the experience of Ferguson's men, unprotected by their anonymous replacements.

The owners were invisible, his chief executive unrecognisable. Moyes, left brutally exposed, was the sole public symbol of a regime ridden with flaws.

Moyes slumps in his seat during United's first leg Champions League defeat by Olympiakos

At Everton, he had excelled at producing reactive teams to counter opponents with greater attacking resources and bigger reputations. At United, that could never be enough, no matter how denuded the playing resources and therefore deluded the cavaliers.

For a manager defined by his discipline, Ferguson was also a natural gambler. Moyes sticks where Fergie twists.

There will be those who point out the similar difficulties Ferguson endured early in his own time at Old Trafford. Moyes won exactly half of his first 34 league games in charge, Ferguson just 41%.

The team of champions that Moyes inherited from his predecessor were also flattered by their 11-point title margin, their flaws disguised by the goal-scoring of Robin van Persie and the struggles of their rivals at Stamford Bridge and the Etihad.

Moyes set a number of records at United he will want to forget

But there were too many other statistics with which he could be damned: losing to both Merseyside clubs home and away for the first time in history; losing at home to abject Newcastle for the first time in 39 years and to Swansea for the first time ever; finishing with fewer than 70 points in a league season for the first time since 1990-1 and their lowest league position in Premier League history; out of the Champions League for the first time since the far harsher qualification rules of 1995.

The only green shoots visible were from seeds of discontent. The rebuilding job had become a demolition.

There was the cruel: Everton, the club he had left behind, liberated by his successor, Roberto Martinez, and playing better football to greater effect than he ever managed; and Liverpool, United's greatest rivals, reborn under the young and charismatic Brendan Rodgers, charging for the title in swashbuckling fashion as United stumbled to seventh.

Moyes went from The Chosen One to The Unwanted One

But there was the fog, the muddle, that seemed to envelop everything Moyes did. What were his tactics? What was his preferred team? Neither players nor fans knew. Increasingly, it seemed, neither did their manager.

Not once did he pick the same team for successive matches. Some of that can be put down to injury, some to a laudable desire to give every player a chance to prove themselves. But injuries happen to every manager. The best quickly sort wheat from chaff. In his final game in charge, Moyes picked Nani against the best full-back in the country.

The epitaph is just as wretched. Failure will now stay with Moyes, even if he goes on to enjoy future successes, not so much a caveat to his career as a defining characteristic.

It is unfair on an eminently decent man and decent manager, but, as Graham Taylor can tell you, such is the weight the biggest jobs carry.

For United, neither is it a happy ending. Moyes was no longer taking the club forward, but his dismissal does not alleviate the urgent need for a new back four, three new midfielders or pace throughout a stodgy team.

Media scrutiny on Moyes increased day by day

An ageing squad a year older, the younger generation a year further from fruition, it has been a wasted season, the club less attractive for both a new manager and fresh players, £70m spent with little to show for it, that monstrous debt still in place.

Every fan thinks their club is special. United were different for having one manager for 26 years, for being a model of stability and long-term success as others rose and fell. Now they realise they are just like all the others. It is an unsettling prospect.

'Only Mourinho could follow Sir Alex'

- Published22 April 2014

- Published22 April 2014

- Published22 April 2014

- Published22 April 2014

- Published21 April 2014