Why are South Americans succeeding in England?

- Published

BBC Sport's State of the Game study has revealed a growing South American playing presence in the Premier League, with Argentina now the third non-UK nation in the top flight. Here South American football expert Tim Vickery explores why this is happening.

Earlier this month Sergio Aguero's goal won the Manchester derby for City. Nothing unusual there, perhaps - the little genius has been a consistent matchwinner since joining the club just over three years ago, with 64 goals in 98 Premier League appearances.

Much more striking is that Aguero was part of a South American contingent which on the pitch that day was more numerous than English players - a fact which serves as a symbol for the season.

In the opening months of this Premier League campaign as many Argentine as Scottish players have taken the field, with 18 each. Chelsea's gang of Brazilians - Ramires, Willian, Filipe Luis, Oscar and, arguably, Diego Costa - along with Philippe Coutinho at Liverpool, have kept the flag flying for the five times world champions.

Alexis Sanchez of Chile has already won the hearts of Arsenal fans, while compatriot Eduardo Vargas has hit the ground running at QPR - as have Uruguay's Abel Hernandez at Hull and the Ecuadorian pair, Enner Valencia and Jefferson Montero at West Ham and Swansea, respectively.

And if Colombia's Radamel Falcao has yet to live up to expectations at Manchester United, at least his international team-mate Carlos Sanchez is starting to get some game time at Aston Villa.

The 2014-15 campaign is proving the season when, at last, South American players are having the kind of impact on English football that they have long been making on the other major European leagues. This begs an obvious question; why has this taken so long?

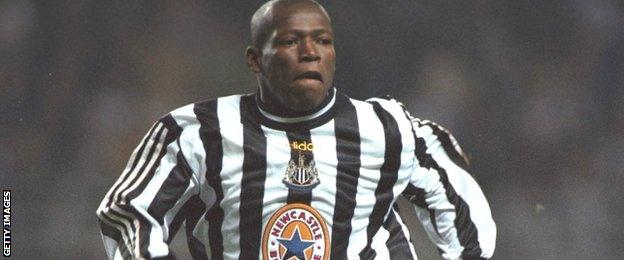

Brazilians Emerson (left) and Branco played for Middlesbrough in the 1990s

In 1996 Terry Venables commented that it was only when he took charge of Barcelona 12 years earlier that he realised the advantages in bringing in top players from abroad. It was an interesting moment for such an observation.

Money was already swirling around the Premier League and big name foreigners were arriving. But as the 1996-97 season kicked off, the only South Americans on view were Gus Poyet at Chelsea, Faustino Asprilla at Newcastle and a group of Brazilians, Juninho, Emerson and Branco at Middlesbrough.

If foreign players were now welcomed, it seemed that South Americans were still seen with a certain suspicion. Could they adapt to English life and the pace of Premier League football?

For some the answer will always be negative. Living abroad is not for everyone. For example, even a player as apparently mature and collected as Michael Owen found it difficult to slot in to life at Real Madrid. "I missed being around English people," and even more bizarrely, confessed to missing "UK weather".

Manchester United flop Kleberson, external was a midfielder with all the technical attributes to succeed. After Ronaldo he was the best player on the field in the 2002 World Cup final. The mental skills, though, were a different matter.

"The most important thing is the head of the player," says Christian Rapp, who heads the Brazilian-based operation of a German company that specialises in looking for talented youngsters.

"The player who wants to have a career abroad needs to make the adaptation to his country and club, not the other way round. This is the big explanation for some cases working out while others don't."

South American struggles |

|---|

No South American player has yet joined the 100 goals club in the Premier League. The top-scoring player from the continent is Argentine Carlos Tevez with 84 goals. |

Inevitably, some South Americans will find the long haul across the Atlantic a bit too much, and without exception they gasp at the speed of the English game.

But as far back as 1978 Osvaldo Ardiles demonstrated that such obstacles were far from insurmountable. The little Argentine arrived at Tottenham fresh from winning the World Cup, with the old guard of English football merrily predicting that he would be home by Christmas.

Hardman Tommy Smith famously said after inflicting a thunderous tackle on Ardiles during an FA Cup tie between Swansea and Spurs that they "can't expect to come here and play like fancy flickers".

Instead, for all his lack of physicality, Ardiles took to his new challenge with ease, giving a weekly masterclass in shielding and moving the ball. But once the point had been made so graciously and emphatically, why did so few South Americans follow in his tiny footsteps?

Perhaps there was a lack of imagination on the part of English clubs. Certainly there was a lack of money. When Italy opened up to foreign players in the 1980s there was no way the English clubs could compete in financial terms. The best South Americans headed for Serie A. And Italy, Spain and Germany had another advantage - the absence of work permit restrictions.

In order to receive permission to work in England a South American player needs either to have a European Union passport - possible if he can trace his ancestry back to Europe - or to be a regular and established member of his national team. The other major European leagues do not have such a restriction, making it easier for them to import players from across the Atlantic.

Colombian striker Faustino Asprilla was a cult figure in his time at Newcastle

This bureaucratic caveat has had a number of consequences.

For one it has meant that English clubs - including until recently the very biggest - could not find it worth their while to invest in a South American scouting network. This in turn means that they are often at the mercy of agents carrying carefully cut DVDs of players they are trying to sell - players who in reality may not be remotely suited to the Premier League.

An example is Argentine striker Mauro Boselli - a proven goal-poacher back home, but a centre forward with a style that meant he was likely to struggle in England.

An agent tried for some time to offload him to a Premier League club - in the end it was Wigan who signed him in 2010. He did not manage a single Premier League goal in a three-year spell that included three loan spells in Italy and Argentina.

Another effect of the work permit situation is that it restricted the flow of South Americans, which made the process of adaptation even harder.

The Premier League swiftly became a global brand, but it took some time for the clubs to adjust to their multi-national dressing rooms. They would buy in a footballer but forget the human being.

Soon after he joined Aston Villa, Colombian striker Juan Pablo Angel's wife fell ill. He was astonished to receive little support from the club. From an upper middle class background, Angel arrived speaking English - which is not the case of most South American imports.

In his first spell at Chelsea Argentine striker Hernan Crespo, external gave an interview to his home press confessing his worries at having to take his car to the garage or deal with the man coming to fix his phone. He lacked the language skills for these daily situations, and was more worried by them than he was by taking on the opposition centre-backs.

Argentines Ossie Ardiles (left) and Ricky Villa (right) were brought to White Hart Lane in 1978 by manager Keith Burkinshaw

South Americans come from cultures that put less importance on individual independence than our own, and many of them have been through a sub-standard educational process. They would expect - and need - help to settle in. It is extraordinary that the clubs dealt with expensive assets in such a lax manner.

Things have changed - Angel speaks proudly of how specialist welfare offers became the norm in England during his time with Villa.

In other countries, though, it did not matter so much if the clubs were not taking such measures; because there were more South American players around, a newcomer could rely on a ready made support structure to help him bed in.

This is the point at which the Premier League has now arrived. With around 50 South American players dotted around the country, critical mass has been obtained. There are enough now to form a welcoming committee for new arrivals. And it is a critical mass of quality.

Long gone are the days when England could not compete with Serie A. True, the two Spanish giants have a cache beyond even the biggest English teams. But the financial strength in depth of the Premier League makes it a desirable venue for top level internationals.

In addition, the pitches are incalculably better than the mudheaps which Ardiles managed to skip across all those years ago - allowing the flair players to show off their skills. And a change in the criteria used by referees has also worked in favour of the South Americans.

More than a decade ago Arsenal's Brazilian midfielder Edu moaned to his local press that in England "there is no such thing as a foul". Today's officials are much quicker to reach for the whistle, giving the players the kind of protection they are used to receiving on the other side of the Atlantic.

And so, at last, English fans are getting a first hand look at the skills from the continent which has consistently produced the finest individual talent in the game.

It was always an anomaly to have a globalised competition without a strong South American input - 2014-15 is the season when the Premier League has completed the jigsaw.

- Published20 November 2014

- Published20 November 2014

- Published20 November 2014

- Published20 June 2016

- Published7 June 2019

- Published2 November 2018