Thierry Henry: The football fan who fulfilled his dreams

- Published

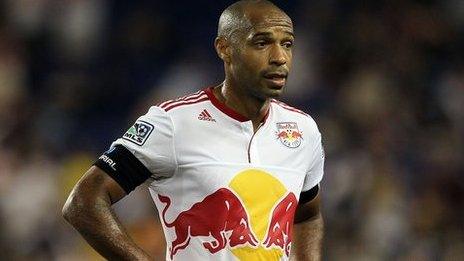

Henry twice helped New York Red Bull to top the MLS Eastern Conference

There is nothing that quite prepares an elite sportsman for the moment when they wake up and don't have a dressing room, a training ground, a life that revolves around preparation and competition to anchor them.

Thierry Henry announced that he would not be staying on at New York Red Bulls on 1 December after his team went out of the MLS Cup, at the age of 37. It has taken the Premier League legend just over two weeks to firm up his future ambitions and opt for a career in the media.

Maybe the tricky business of letting go of a vocation that has shaped a person from their teens onwards was too big a deal to do like clicking fingers. Henry was 13 when he passed the exams to be selected for the Clairefontaine academy run by the French Football Federation and stepped into the creme de la creme sporting world he has been in ever since.

Even for a stunning success story like Henry, whose personal medal haul includes an array few footballers can match, the next chapter can be daunting.

But Henry instead - for now anyway - joins a set of the brightest and most communicative of ex-players in choosing the media instead of management as a focus. For the likes of Gary Neville, Lee Dixon and Danny Murphy, their critical eye is about observing the Premier League now rather than shaping it from within, which reflects on the ramped up pressures these days.

One quality he would bring to the job is an encyclopaedic knowledge of football over the past couple of decades.

Some players - Lionel Messi is a notable example - just dedicate themselves to playing. Some players prefer to be relaxed enough about the finer details to not even have much interest in who his team might be playing next, or the formbook of opponents.

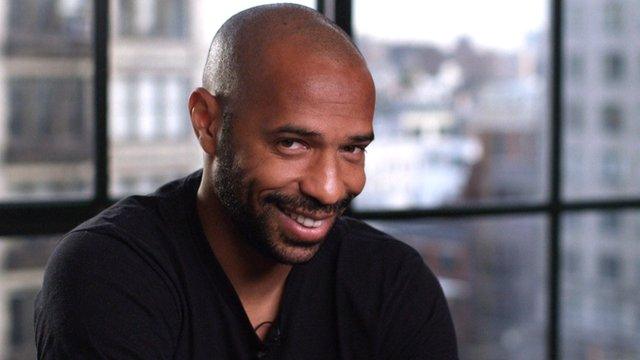

Henry's appetite for football has always been insatiable. His memory for the minutiae of a particular game, how a player fared in a particular situation, scores and records and strengths and weaknesses of teams across world football, has always been striking.

A statue of Thierry Henry at Emirates Stadium was unveiled in December 2011

His knowledge was unusually precise - perhaps displaying a hint of a manager's eye - throughout his playing days. It was not uncommon for Henry to surprise a journalist whose opinion he disagreed with with a phone call in order to politely pick apart a theory he couldn't accept.

Dennis Bergkamp found it astonishing. "Sometimes he would phone up a newspaper," recalls the former Netherlands and Arsenal forward.

"I was thinking I can't believe that he does that. When somebody would say something, where I would say just leave it, he would phone them up and say, 'OK, this is what I think, this is my opinion'. It's very strong."

Henry watched and evaluated football relentlessly. In his early days at Barcelona, when he was struggling to find his rhythm in this new environment, one evening he bumped into some old acquaintances and sounded somewhat jaded when talking over his situation.

Then he suddenly became animated, and full of enthusiasm, when discussing a match from England's second tier he had seen on TV the night before.

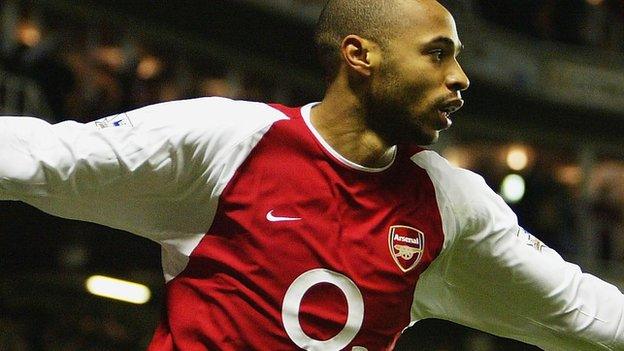

It was this kind of intense interest in the game outside of his own daily aspirations that generated a feeling for the club he would become most connected to - Arsenal - before he joined them.

Thierry Henry has been known to call journalists to discuss matters where he has disagreed with them

He had a reason to keep an eye out for them when he was still a youngster at Monaco, and briefly, a Juventus player. Not only was his old manager Wenger there, but also team-mates from France's youth teams in Patrick Vieira and Nicolas Anelka.

He knew all about how Arsenal played before he was signed in 1999.

When he arrived, he was given a video of all Ian Wright's 185 Arsenal goals and studied them. This self-taught element of his education was important in two ways - he watched the runs, the finishing, the patterns which he would absorb into his armoury as he relearned how to be a striker after several years playing wide.

He also soaked up the history and began to feel the roots growing deeper in terms of his attachment to the club.

Naturally, a homegrown player tends to have more of an innate affinity to a club. The likes of Paolo Maldini (AC Milan), Steven Gerrard (Liverpool) or Xavi (Barcelona) epitomise that connection that goes back to boyhood.

In Henry's case, the union came later and developed over time. But it was evident how much his dominant club got under his skin as the years passed.

In fact, he became so into it that when he returned to Arsenal for a second stint on loan in 2012 (five years after leaving) he found the whole experience overwhelming because he had felt himself change from being a player to a supporter.

"I get upset like a fan. I think like a fan. People can think what they want but it is true love," he said.

And then, as the former player-turned fan playing again, he scored a goal that turned out to be one of the most important moments of his career.

It came against Leeds in the FA Cup on a chilly night in January 2012. It was not on the surface the most crucial thing he ever did, but it packed the biggest emotional punch.

Henry took a detailed approach to knowing everything he could about opponents during his playing career

"I played in some big games for Arsenal, Barcelona, France, Juve, Monaco… nothing will ever top that night for me," Henry said.

"I really thought I was in a dream. I remember staying in the dressing room for two hours just contemplating. To score a goal again for Arsenal was out of this world."

If he does return to north London, he will bring much more than affection and status. As an unyielding student of the game, in his years he has observed an array of managers with different nuances - World Cup winner Aime Jacquet, Wenger and Pep Guardiola were particularly influential.

He has played alongside an array of team-mates with diverse skills - Zinedine Zidane and Lilian Thuram, Dennis Bergkamp and Tony Adams, Messi and Xavi, and against a generation that includes Gianluigi Buffon, Philipp Lahm, Didier Drogba, Cristiano Ronaldo et al.

There is a lot of football that has already been forensically analysed in his head that ought to be a very useful part of expertise for the future.

The range of experience he can bring to football if he decides he wants to lead and educate others is very broad. He knows how it feels to win the World Cup, and to blow it as France did in the 2006 final.

He has won the Champions League with Barcelona, and lost a final with Arsenal. He has been honoured many times as Footballer of the Year, and lambasted for a high-profile handball which called into question his sporting integrity.

There is a lot stored away to pass on. "Thierry is always talking," says former Gunners team-mate Sol Campbell. "He just wants to know everything and tell you about everything."

Henry's latest venture should allow him to express himself as freely as he did on the pitch.

- Published16 December 2014

- Published16 December 2014

- Published16 December 2014

- Published16 December 2014

- Published10 December 2011

- Published2 December 2014

- Published2 December 2014

- Published1 December 2014

- Published6 January 2012

- Published30 December 2011