Premier League: Football broadcasting battle hots up

- Published

Premier League TV deals cost fans too much - Mockridge

Spare a thought for West Bromwich Albion fans hoping to watch their team live on television this festive season.

Because, despite 36 Premier League matches being shown on either Sky or BT in December and January, the Baggies are not scheduled to appear once.

The way Tom Mockridge sees it, this is simply unfair.

Unfair on those supporters who cannot get to their club's matches, and if the Virgin Media chief executive had his way, it would change.

In fact, the 60-year-old New Zealander could just be the biggest threat the Premier League has faced to date.

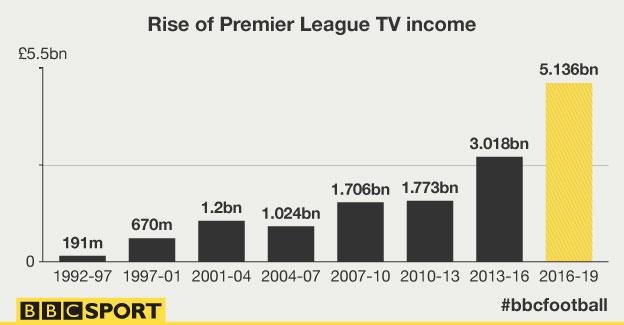

The league's policy of making 168 of the league's 380 matches available to live TV helped it secure a record-breaking £5.1bn rights deal earlier this year. With limited supply, the demand from both Sky and BT reached unprecedented levels, the three-year deal from the 2016-17 season worth a remarkable 71% more than the current one.

Ofcom is investigating the Premier League's sale of TV rights and a decision is expected in 2016

Virgin Media reckons the result is that UK viewers pay twice as much more for top-flight games than their European counterparts do for respective leagues on the continent.

Last year, Virgin Media complained to regulator Ofcom, which launched an investigation, external into the league's sale of TV rights, and a decision is expected next year.

"Fans are paying too much for pay TV football," Mockridge, a former chief executive of News International who is now taking on his old boss Rupert Murdoch, tells me firmly in an office at his company's headquarters in Hammersmith.

"At the moment only 40% of Premier League games are available on national TV in England and some clubs are only on six times a season if they're lucky. That's just not fair.

"Ofcom should look at whether they're keeping too many games from television. If you hold something back the price goes up, maybe too quickly. This is a very, very big decision not just for football, but for the UK.

Mockridge's argument is simple. The league's collective selling of TV rights is contrary to competition law. Limiting the number of matches shown keeps them artificially expensive. Show more games live, offer real choice, and then prices will come down.

Furthermore, because matches are currently shown exclusively - i.e. either on Sky, external or BT,, external fans have to buy both packages to watch their team as many times as possible. So make all games available on a number of competing providers, and give customers a real choice of provider.

However, while Mockridge may want to portray his company as some kind of consumer champion, there is an ulterior motive of course.

Virgin Media is angry at what it sees as an inflated wholesale market and the amount it is now having to pay BT and Sky to show matches on its platform. Mockridge does not deny that self-interest is behind the stance, but refuses to apologise for fighting what he sees as an anachronism.

In 2005, the European Commission allowed the Premier League to sell collectively, but ruled that no one provider could broadcast Premier League matches live, bringing an end to Sky's monopoly. The competition commissioner succeeded in having the bidding process opened up, the idea that greater choice would benefit the consumer. But Mockridge believes while that may have been the intention, in reality the opposite has happened.

"The Premier League shouldn't be able to say it's exempt from normal competition law. It should be treated like a big business. It's a great business and has done a terrific job," he says.

"But if you go across Europe almost every football game in the major leagues is available on television, the same in the States with NFL, MLB and the NBA."

However, the Premier League is resolute in its defence of the way it limits the number of matches made available on live TV.

Since the 1950s, no league matches on Saturday afternoon have been broadcast. This traditional 3pm-5pm 'blackout' is designed to protect attendances at matches up and down the country, throughout the divisions.

And fans are on the Premier League's side of the argument. According to the Football Supporters' Federation, "the majority of our members support the blackout, and the main reason for that is its importance to the economic survival of clubs lower down the football pyramid".

It adds: "Is there another country on the planet which could draw 47,000 for a fifth tier play-off final as Bristol Rovers and Grimsby Town did last season? We don't know of any. That unique aspect of our game deserves protection and we've heard in the past from the CEO of teams such as Macclesfield Town who say, external they can lose as many as 400 from their gate when competing with games involving local Premier League clubs."

Price of Football: 20 clubs, 50 shirts, one summer

Mockridge rejects that argument, suggesting US-style regional blackouts, external could be a solution, as could an alternative method.

"You could address ticket prices," he says. "An organisation making £5bn could maybe make prices a little more accessible."

Mockridge points to Germany where all the Bundesliga matches are available live on TV, but stadiums are mostly full.

The Premier League counters that in Germany there are only 38 professional teams - as opposed to 92 - and that these two footballing countries should not be compared. It adds that regional blackouts simply would not work in a small country like the UK, and that from next season, more matches will be available on TV than ever before, including on Friday nights.

It also disputes the suggestion that the rise in rights costs has been passed on to viewers, where the cost of a TV sports package has gone up only slightly.

What is undeniable is that as the Premier League approaches its 25th year, the inflation in live TV rights has been the principal driver of its astonishing commercial success.

While players and their agents have been obvious beneficiaries, the Premier League makes the point that the money has also been redistributed for the benefit of the game - in terms of stadium development - and for society - through tax receipts, solidarity payments and funding towards a range of good causes. Any threat to the way it conducts this part of its business therefore could have serious ramifications for the football community, as well as for Sky and BT.

More on the BBC's Price of Football study: |

|---|

Mockridge insists that if Ofcom rules in his favour, and all matches are made available on TV for the next contract starting in 2019-20, the Premier League could make even more money, but fans (and Virgin Media of course) will pay less.

"The system should be fair, and the consumer should be represented," he says. "I would say any objective observer would look at this and say football's become so expensive, consumers are no longer benefitting."

The fact that Ofcom has been looking into this case for well over a year now ("the biggest piece of consumer research it has ever done", according to Mockridge), is indicative of just how complex an argument this has become.

But with so much at stake, one suspects that all those awaiting the outcome would much rather the regulator takes its time before making a decision that could change the game forever.

- Published16 December 2015

- Published15 December 2015

- Published14 December 2015

- Published14 December 2015

- Published15 December 2015