'Man City's Claudio Bravo is a playmaker not sweeper-keeper'

- Published

In Manchester City's past two games, Celtic and Tottenham both chased down their goalkeeper Claudio Bravo relentlessly, closing down his angles and denying him time on the ball.

It is going to keep happening. Teams have realised how important Bravo's passing is to City's style of play under Pep Guardiola, and are trying desperately to stop it.

But that does not mean Guardiola will change the way his side use Bravo when they play Everton on Saturday.

When Spurs and Celtic put Bravo under pressure in his own box, their fans got excited because he was taking risks in an area that could cost City a goal.

But the reason both teams did that was actually a defensive ploy.

They know how important possession is to City's attacking play under Guardiola, and one of the ways to deny them the ball is to force Bravo to play it long.

When he does that, City are far more likely to lose the ball. They have the highest average possession rate in the Premier League this season (63.1%), so that is something they don't like happening often.

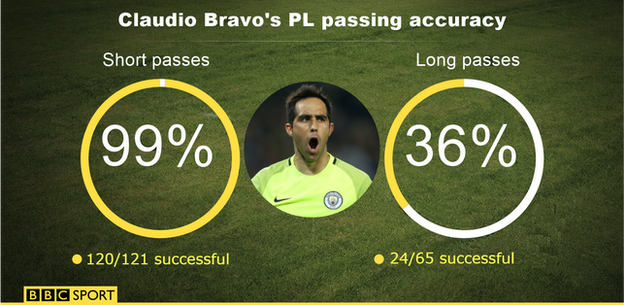

In four games for City, Bravo has played more short passes than any other Premier League goalkeeper this season (including keepers who have played all seven fixtures), and only one of those passes failed to find a team-mate

For some teams, that is not an issue.

At the other end of the scale to Bravo, West Brom have the joint-lowest possession rate in the Premier League this season (37.8%).

The way the Baggies use their keeper is drastically different - Ben Foster goes long 92% of the time, and only finds a team-mate with 30% of those passes.

They play the percentages, thinking that even if they lose the ball most of the times they play it long, it is worth it for the times they win it high up the pitch from the first or second ball.

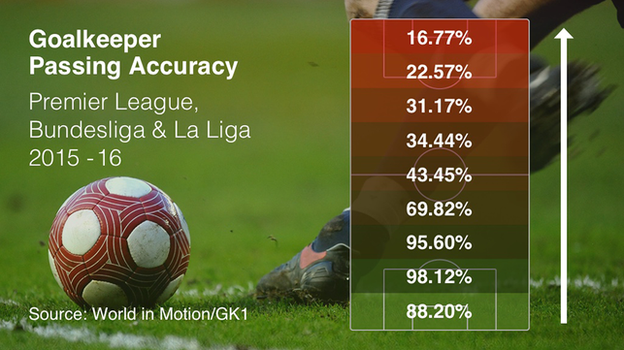

Apart from the bottom sector, which sees more 'emergency' clearances launched into touch, goalkeepers' success with their distribution decreases with the distance it travels from their own goal. Graphic shows combined passing accuracy from goalkeepers to have played more than seven matches in 2015-16. This data has been provided by World in Motion, a global football agency who represent over 70 goalkeepers and goalkeeping coaches through their goalkeeping-specific arm, GK1 Management

Bravo more midfielder than sweeper-keeper

Bravo is only six games into his City career but it is already clear the Chilean is being used in a very different way to the sort of 'sweeper-keepers' he was compared to when he signed.

Tottenham's Hugo Lloris is probably the best example of that type of player. He is also comfortable with his feet and happy on the ball outside his area.

Sweeper-keeper Lloris - risky or brilliant?

But his main role is as a last line of defence - to patrol the edge of his area and be ready to offer his back-four cover when balls are played in behind them.

Lloris essentially operates as an extra defender when Spurs do not have the ball. Bravo, on the other hand, is more a deep-sitting midfielder than a defender.

He is used by City to start attacks when they get possession, to help them set their passing tempo and allow them to play up the pitch right from the back. When the opposition close him down, they leave space behind them for City to exploit.

Even if Bravo were to make a mistake playing it out that directly led to a goal, it would not change anything, because he is so fundamental to the way they move the ball forward.

Bravo seeing even more of the ball than he did at Barca

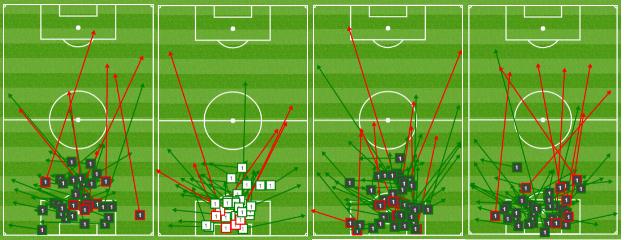

Bravo's successful (green arrows) and unsuccessful (red arrows) passes in his four Premier League games for Man City so far against (from left) Man Utd, Bournemouth, Swansea and Spurs. Out of a total of 121 short passes, his only unsuccessful one came against Bournemouth - the red arrow to the left of the area in the Swansea game was a launch into touch so classed as a long pass

In his first four Premier League games, the Chilean has received 127 passes from his team-mates, or an average of 31 a game.

Last season his predecessor at City, Joe Hart, received 303 in 35, an average of less than 10. Lloris, who made more touches with his feet than any other top-flight keeper in 2015-16, averaged 14.

Bravo is seeing even more of the ball than he did for Barcelona in La Liga last season but he is still using it the same way - when he can - making lots of accurate short passes.

Bravo has played 30 short passes per Premier League game for City compared to 18 short passes per game for Barcelona last season, when he made the most short passes by any goalkeeper in La Liga

When Bravo is not closed down, and sometimes when he is, the vast majority of his passes are to his centre-halves or Fernandinho.

That's because when he gets the ball, City's full-backs push up, their two centre-halves split and go to either side of the 18-yard box to get the ball, and the anchor midfielder drops between them in the middle.

Who does Bravo pass to? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Games together* | Passes from Bravo | Mins per pass | |

John Stones (CB) | 4/4 | 35 | 8.8 |

Nicolas Otamendi (CB) | 4/4 | 30 | 10.7 |

Aleksandar Kolarov (as CB) | 1/4 | 14 | 6.4 |

Fernandinho (CM) | 4/4 | 23 | 15.6 |

Aleksandar Kolarov (as LB) | 3/4 | 12 | 20 |

Pablo Zabaleta (RB) | 2/4 | 2 | 51 |

Bacary Sagna (RB) | 3/4 | 3 | 86 |

Gael Clichy (LB) | 1/4 | 1 | 90 |

Sergio Aguero (CF) | 2/4 | 2 | 90 |

Kelechi Iheanacho (CF) | 3/4 | 2 | 117.5 |

*Including as substitute | |||

From a goalkeeper's perspective, Bravo is the lynchpin but it is the movement of those players that means City's approach is successful.

If they do what they are supposed to, then as a keeper you can almost shut your eyes, receive the ball in a given position and know where you are going to pass it because of the amount of times you have repeated that pattern of play with them in training.

On the other hand, your keeper could be awesome on the ball but if your back five, including that midfield anchor, do not read the cues and move into the right places when he is under pressure then playing short will end in disaster - your keeper will still play the same pass as planned, but will look a right mug when he gives the ball away.

Manchester United were the first team to put Bravo under pressure - in the second half of his debut at Old Trafford

That back five also need to be comfortable collecting the ball deep in their own half when they are being closely marked, like they were at White Hart Lane when Spurs man-marked them from Bravo's goal-kicks and pinned them high up the pitch.

Doing that is a risk, because Spurs players were left one-on-one everywhere else, which is not ideal if you end up having to deal with a long ball forward.

But it seems to be the better case scenario. There is no positive side to letting City play out from the back, so it is a gamble worth taking.

Could Joe Hart have done this job?

Hart had the same short-passing accuracy rate last season as Bravo in 2016-17 but played only 201 short passes in 35 Premier League games. Bravo has played 121 in four.

As he showed in England's draw against Slovenia this week, Joe Hart is an excellent goalkeeper. His kicking statistics are actually pretty decent too.

But if you were writing a job description for what Guardiola wants from that role, Hart was not the best man to do it - Bravo is.

It is the same in any other position at every other club. If a player does not have the attributes to play the style of football that the manager wants, they are not the right player for the team.

In attack for example, a striker Andy Carroll would not fit City's style, or the way Leicester use Jamie Vardy.

You would not play the same way with both players.

I still think Hart could have improved enough to do what Bravo does, because the technical aspect of receiving a back-pass, taking a touch and distributing it short is pretty simple.

But the difficult thing is doing it under pressure, which Bravo has to do 30 or 40 times a game.

Hart could have mastered it, but it might have taken him six months and Guardiola needed someone who could do it right from the start.

Why kicking is important for every keeper

Manchester United goalkeeper David de Gea takes part in possession drills with outfield players during training

As well as shot-stopping, things like efficient communication and dominating your area are the other key skills you need as a modern goalkeeper.

I would put distribution top of that list, however, because if you think about what skill is repeated the most during a game for a keeper nowadays, it is using your feet.

Whoever you play for, keepers make more touches from back-passes or dead-balls than they do dealing with shots or crosses with their hands.

I would class it is as a busy game if I made more than five saves, and it is the same in the Premier League this season where the average number of shots on target a team has managed per game is 4.3.

So what do you do with the ball when you get it at your feet? In the past, it partly came down to how far you could kick it - the traditional way a keeper would hurt opposition teams was with direct play, with big kicks forward.

When I started playing, the only work I did on distribution in training was about the accuracy of my long kicks.

Schmeichel launches one of his trademark throws

Even things that were seen as revolutionary, like Peter Schmeichel's throws to launch counter-attacks for Manchester United in the early 1990s, were designed to get the ball up the pitch as quickly as possible.

With the way City build from the back, using Bravo, Guardiola has turned that on its head. He also has exactly the right keeper to implement it.

Bravo a decent shot-stopper too

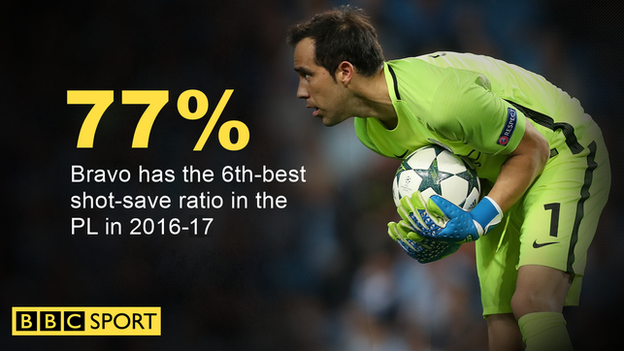

Bravo has saved 13 of the 17 shots on target he has faced. Tottenham's Hugo Lloris has the best shot-save ratio in the Premier League this season, with 87%. Joe Hart's ratio last season was 66%

Bravo is being used differently but, when goals are conceded, it is the same for him as every other Premier League goalkeeper in that ultimately he is the player who will get the blame.

All goalkeepers are used to getting stick - I got conditioned to it when I was growing up. It is how you deal with it that is important.

Bravo showed he could cope when things go wrong with his performance on his City debut against Manchester United at Old Trafford.

Some of the criticism he got was justified - he did not shout when he came out for the cross that he dropped to allow Zlatan Ibrahimovic to score - but he did not let that error affect him.

Similarly, United were the first team to start chasing him when he received the ball but what was noticeable was that City did not stop giving him the ball, and he did not stop trying to pass it short.

Pep Guardiola praises Claudio Bravo

He has clearly got a lot of confidence or, what I call bouncebackability - the resilience you need to move on when you make a mistake.

So I am not surprised he has gone on to make such a solid start at City in the games he has played since.

Far from being a weak link, it looks like a brilliant decision by Guardiola to sign him, especially because of the way City play. He is already an integral part of their team.

Thanks to World in Motion's Head of Research & Analytics, Sam Jackson, who specialises in statistically analysing goalkeepers, including goalkeeper distribution.

Rachel Brown-Finnis was speaking to BBC Sport's Chris Bevan.

- Published12 October 2016

- Published6 October 2016

- Published14 January 2018

- Published7 June 2019