Football has become middle class, claims Andy McLaren

- Published

Andy McLaren: Football's become middle class

Scotland widely bemoans a lack of footballing talent emerging to match the stars of yesteryear.

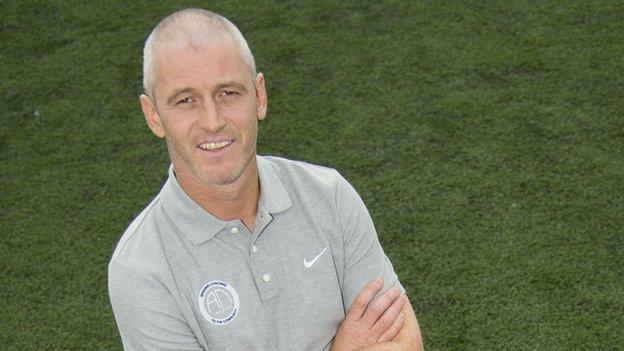

As the national side sees out what appears to be another failed attempt to reach a major championship, former international Andy McLaren feels the game has abandoned a once rich source of talent.

He's providing football sessions in some of the most deprived areas of Glasgow, to kids who can't afford to pay to play.

"Football, in my opinion, has become middle class," McLaren told BBC Radio Scotland's Sportsound programme in an interview to be broadcast on Monday evening.

"It's an absolute disgrace that kids are being priced out of football in this country.

"It's meant to be our national sport. It's meant to be all-inclusive. At the moment it's not.

"I would have been priced out of football just now.

Andy McLaren signed for Dundee United in 1989 aged 16 and stayed at Tannadice for almost a decade

"I grew up in Castlemilk, a housing estate on the south side of Glasgow. Up until I was 15, I thought that was the way everybody grew up.

"Crime, heroin, drink - football was my escape route from all of that. Football was important, took me away from an area that was hard growing up in. It gave me something to focus on."

McLaren is part of a charitable organisation trying to give young people opportunity, particularly through football but in other ways too, in order to tackle the stark disadvantage that simply being born into a certain postcode can bring.

'Missing out on the next Dalglish'

He feels the game he loves, which did so much for him, is now leaving those kids behind.

"I've been working in these areas for seven, eight years and I think I've seen an SFA coach once," he said.

"Remember these are areas guys like Kenny Dalglish, Frank McAvennie, Bertie Auld (came from); really we could be missing out on the next Kenny Dalglish because he's not got a fiver a week.

"For me that's wrong; it's meant to be our national sport."

That's the nub of the problem as far as he sees it. Families in these areas simply can't afford to pay for their children to participate in football.

"I keep hearing that kids don't want to play football," he explained.

"Come up and see us on a Friday night or come to one of our camps and see 200-250 boys running about and tell me kids don't want to play football.

"People keep telling me that cost isn't an issue - 100% cost is an issue.

Andy McLaren claims he would have been unable to play football had he been growing up now

"We're not getting the same kids from the same areas. Growing up in Castlemilk I genuinely can't remember paying for football. Maybe it was 10 pence or you sold a football card now and again.

"People are struggling out there. We started eight years ago and very quickly we'd see young people with holes in their shoes and things like that.

"Some would turn up for camps with no packed lunch. Very quickly we learned we had to feed them because the coaches were having to give them their lunches.

"People will go to me, 'it's the parents' fault' but people out there are struggling with mental health issues or addiction issues.

"I think we're easy in this country to blame people. If you see someone struggling it's our job to help the less fortunate.

"As a society, I think we can do a lot more.

"Areas we work in are areas of high deprivation, the top 5% of every poverty chart you can get.

"If we charged £1 we wouldn't have the same success because the money is not there."

Football as salvation

As a former professional with Dundee United, Kilmarnock, Reading and Morton, McLaren is keen not only to give children of a similar background to his a chance, he also wants them to learn from his mistakes.

Those mistakes took the form of a reliance on alcohol and drugs through much of his playing career. He did that as he couldn't cope with a harrowing experience as a child.

McLaren was abused at a young age by someone in his local community. Ultimately, it brought him to the point of almost taking his own life.

Shame, fear, embarrassment, blaming himself and the dressing room environment had all prevented him from unburdening himself for decades.

Football was his salvation rather than part of the problem.

"Some nights I'd be struggling," he admitted. "I didn't know how to deal with what I was dealing with.

"I wasn't taking them (drugs and alcohol) socially. I was taking them for effect.

"It wasn't as if anyone forced me to do anything. I was a willing participant. I enjoyed it."

McLaren believes a failed drug test while playing at Reading saved his life, as did the support of the English FA who paid for him to rehabilitate at the Priory clinic.

He was talented, won a Scottish Cup with Dundee United, and remarkably battled back after falling from grace to win a Scotland cap. He may have had more.

Thankfully, for all the negatives of his own experience, there's a positive outcome which is benefiting children growing up in areas like he did.

- Published20 March 2017

- Published20 March 2017

- Published20 March 2017