'£6,500 buys a penalty" - how corruption eats at the heart of Algerian football

- Published

Algerian fans are massively passionate - but how much can they trust what they watch?

Algeria has a legitimate claim to be called a football-mad country. But it is not all about passion, culture and history. Another kind of madness is eating at the heart of its football.

"It is easy for everyone to fix matches and arrange results", a match-fixer told the BBC.

"You just have to understand the process and the tricks."

According to him, and to multiple sources - intermediaries, past and current players, referees and football executives, initiators and victims of bribery and corruption - who were approached by BBC undercover operatives in the course of a three-year investigation, systematic, systemic corruption has been allowed to go unchecked at every level in the Algerian game.

As one of Algeria's former senior football executives put it, in his country, football is 'not just a game'.

A former senior Fifa executive went further and told us: "Algerian football may have already passed the tipping point".

Corruption a la carte

Algeria's national team has struggled in recent years, despite the presence of stars like Riyad Mahrez

According to the information which has been obtained by the BBC, bribery of players and officials is so commonplace in Algerian football that there is a quasi-official 'price list'.

The list is agreed by all parties, and determines how much it costs to buy players and officials - corruption a la carte - given the context and importance of a particular game.

In the First Division, for example, the award of a penalty kick by a corrupted official will cost a minimum of DZD1m, the equivalent of £6,500.

This in a country where international-qualified referees earn less than 10% of this sum in a month.

Meanwhile a draw will cost twice as much, a win and three points over £50k.

Prices will go up as the end of the season draws nearer and a title - or escaping relegation - can be bought.

Nor is the corruption limited to the top two divisions of Algerian football: even youth team games are affected.

"It's really hell there [in the lower divisions]", the chairman of a professional club told one of our investigators. "Violence, corruption - you have all the plagues".

The weaponisation of Algerian football

Algeria fans have been left disappointed by the national team's performances

Everyone appears to know how the system works.

"We know them [the corrupters], but no one does anything", a former high-ranking official of the Algerian FA told the BBC.

"It's a political problem, (and) when politicians interfere in football, it's the end."

Knowing references to "strange" results are routinely made on Algerian media. Club presidents publicly bemoan corruption.

But naming the culprits and addressing specific instances of bribery is another matter, however, which is why our sources insisted on their anonymity being respected: speaking out would put the whistleblowers at risk.

"In Algeria, there is no place for heroes", a respected Algerian football commentator told us. "They will be victims".

What's more, wealthy "superfans" can sometimes be complicit in the fixing of games which they openly discuss online and in their messaging groups, when they don't bend results themselves by using intimidation and violence.

A bad result

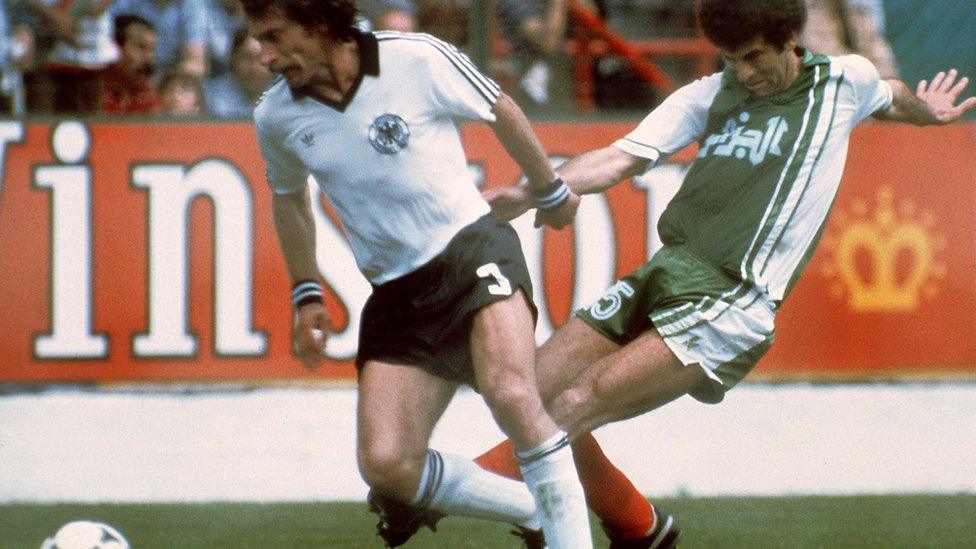

Algeria's win over West Germany at Spain '82 was the first by an African side at a World Cup

The current Algerian football administration campaigned on an "anti-corruption" ticket and, among other initiatives, has set up an Audit Commission to monitor the finances of the professional leagues and of the Algerian FA itself.

Despite that, intermediaries told the BBC that they were still actively involved in match-fixing in 2018.

Moreover, there are indications that the state of the domestic game is now impacting the performances of the national team, which has come to rely overwhelmingly, and controversially at home, on footballers of Algerian descent who were born and trained in France, the old colonial power.

The Fennecs, who gave Africa its first ever win in a World Cup when they beat European champions West Germany in 1982, didn't win a single game at the 2017 African Cup of Nations - and failed to qualify for the Russian World Cup.

It is no exaggeration to say that the footballing future of one of the continent's historic powers - where the first football clubs were established in the 19th century and whose players were at the forefront of the struggle for independence - is in jeopardy.

This is not because a lack of talent, but of a barely comprehensible level of corruption within the domestic game, the extent of which is revealed for the first time in this investigation.

Fifa, football's world governing body, was made aware of the BBC's investigation. A spokesperson for the organisation told the BBC that Fifa "takes the issue of match manipulation very seriously as we believe that protecting the integrity of football is paramount" and indicated that Fifa were "looking into the matter and gathering additional information" and that the information provided by the BBC had "been forwarded to the relevant Fifa departments and bodies in line with our standard procedures".

The BBC understands these departments and bodies to be the Investigatory Chamber of Fifa's Ethics Committee and Fifa's Disciplinary Committee. Fifa also encouraged anyone who could contribute information on this or any other issue affecting football's integrity to contact their dedicated reporting platform BKMS.

When the BBC put its allegations to the Algerian football authorities, Kheireddine Zetchi, president of the Algerian FA (FAF), whilst not answering directly any of the specific questions which had been put to him, replied that "cleaning up football is one of the priorities of the current management team", but that "the facts to which [the BBC] refers date from a time when the current Federal Bureau was not in place", ie, before March 2017, when Mr Zetchi was elected FAF president.

The BBC investigation took place over the 2015-16, 2016-17 and 2017-18 seasons.

Zetchi added that "the professionalisation of Algerian football has taken such turns as to imperil the existence of our clubs and of the king of sports in our country" and, referring to the testimonies gathered by the BBC that it was the FAF's "duty to verify the veracity of assertions made by anonymous witnesses."