Diego Maradona: How tormenting England made him an Argentine deity

- Published

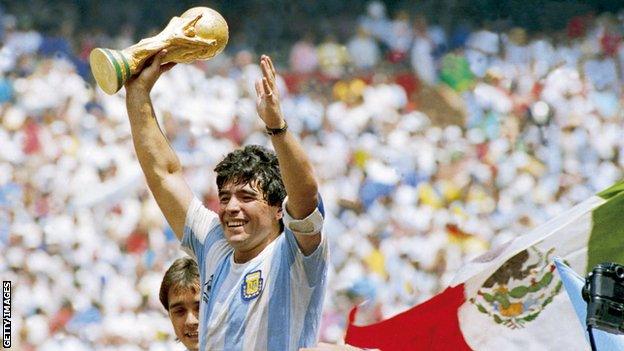

Diego Maradona won the World Cup with Argentina in 1986

In the history of football's World Cup, it is arguable that no player has ever hit the heights achieved by Argentina's Diego Maradona in 1986.

Brazil's Pele, usually seen as Maradona's rival in the quest to be considered the best ever, won the competition three times surrounded by colleagues of outstanding quality.

But many football fans would struggle to name many of Maradona's team-mates from 1986.

In game after game in the Mexican sunshine Maradona was an individual genius and a collective strategist.

He produced the pass that won the final against West Germany and was perhaps at his best in the semi-final against Belgium, where he scored twice.

But it is the quarter-final against England that stands as the defining moment of his life. In the build up to the game much was made of the war between the two countries in the Falkland Islands just four years earlier. From the Argentine point of view the symbolism went much deeper.

Watch all of Maradona's World Cup goals

Nineteenth and early 20th century Argentina had been an informal part of the British Empire. The introduction of football is a consequence of British influence.

The game arrived full of World War One prestige. It moved down the social scale and was re-interpreted by the locals, transformed into a more balletic sport ideal for the player with a low centre of gravity - very true of the squat, little Maradona.

And the reinterpretation led to international triumphs and recognition for a part of the world starved of such attention.

Nobody embodied this story better than Maradona. His roots mixed Italian immigrant with indigenous American. He grew up in the poor periphery of the urban sprawl of Buenos Aires and grew into an incarnation of the 'pibe' - the street kid forced to live off his wits.

He was, then, an everyman Argentine, who lived out a national fantasy with the way he scored his two goals in that 1986 quarter-final win over England.

The first was the notorious 'hand of God' goal, when the referee did not spot that Maradona had flicked out a hand to deflect the ball past England goalkeeper Peter Shilton.

Diego Maradona explains his infamous 'Hand of God' goal

Less than five minutes later he followed it up with one of the great solo goals, gaining possession in his own half, with the ball seemingly tied to his left foot, slaloming his way through the entire England defence before sliding home.

On BBC radio, Bryon Butler described it perfectly, picking up momentum along with the Argentina captain.

"Maradona," he began, "turns, like a little eel and comes away from trouble. Little squat man, comes inside [defender Terry] Butcher, leaves him for dead, outside [the other centre back Terry] Fenwick, leaves him for dead - and puts that ball away. And that's why Maradona is the greatest player in the world. He buried the England defence!"

Both goals were interpreted at home as acts of revenge from those who had been on the weaker end of a colonial relationship.

The controversial first appeared as a message of 'they have the formal power but we are smarter'.

And the glorious second was an irresistible claim that 'we are better'.

Scoring those goals, against that opponent, turned Maradona almost into a deity in the eyes of some of his compatriots - with disastrous consequences. Living the aftermath was not easy.

Roberto Perfumo, a highly intelligent former Argentine captain, once made an interesting comparison. Roman emperors had people walking behind them, whispering reminders in their ears that they were only mortals. Argentine society, said Perfumo, had tended to do the opposite with Maradona.

The limits were taken off him - in Argentina and in Italy, where he was playing the best football of his club career. Maradona began with Argentinos Juniors, and had a brief but fondly remembered spell with Buenos Aires giants Boca Juniors.

Then came the move to Europe to join Barcelona. He felt more at home, though, with Napoli, where he readily identified with the population in the south of Italy and their hurt at northern discrimination.

Diego Maradona inspired Napoli to their first league titles in 1987 and 1990 - and the Uefa Cup in 1989.

Inspired, he carried Napoli to two rare league titles at a time when the Italian championship was the best in the world. And, just as in Argentina, he was indulged. It was in Naples that he developed a cocaine addiction.

Some of this may have been the desire to blot out physical pain. Maradona's playing career coincided with a physical evolution of the game, but came before referees gave more protection to skilful players.

Week in week out he was on the end of brutal treatment from opposing defenders, and was clearly in physical decline even as he took an ordinary Argentina side to the final of the 1990 World Cup.

After that it was consistently downhill. He was suspended for testing positive for cocaine, and when he tried to make a comeback in the 1994 World Cup he was found to have taken an illegal substance to aid his weight loss and was kicked out of the competition.

Without the discipline of football, the second half of his life was a chaotic affair.

His weight ballooned and he went through a number of much-publicized health scares.

He became an outspoken political figure; once linked with Argentina's military dictatorship and then with right wing president Carlos Menem, he moved to the left, becoming friends with Fidel Castro and tattooing himself with the image of Che Guevara.

But it was in football that he seemed to find his peace. As a fan, he would turn up at the stadium of his beloved Boca Juniors, take off his shirt, swirl it around his head and lead the chanting.

And he chose to work as a coach, taking charge of teams in Mexico and the Middle East as well as Argentina. He coached the Argentine national team at the 2010 World Cup.

For many his spontaneity and fallibility were part of the appeal. Maradona was the opposite of the polished PR act of the post-playing career Pele.

His admirers thrived on the way he would fall down only to get back up again. It humanised a figure whose epic life was as mazy as one of his left-footed dribbles.