Fyodor Cherenkov: The Soviet football genius the world never got to see

- Published

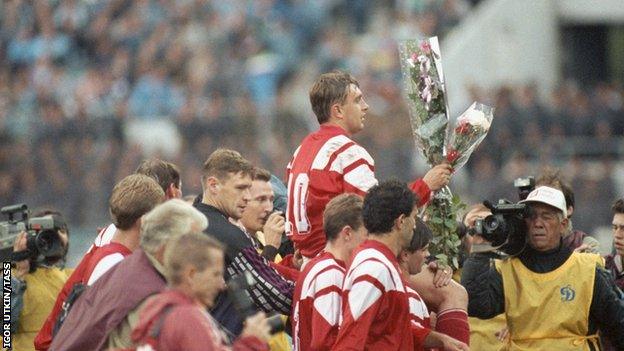

Cherenkov, pictured after his final match for Spartak in 1994

"They're trying to poison us!" Fyodor Cherenkov screamed as he refused to eat the soup.

His Spartak Moscow team-mates, alongside him in the dining room, were stunned. It was March 1984, and they were preparing for the return leg of a Uefa Cup quarter-final against Anderlecht, taking place in Tbilisi because of cold weather in the Soviet capital.

The Belgians had won the first leg in Brussels 4-2, but Spartak fancied their chances. They had a brilliant team, the best in a generation. But now something wasn't right with their star player.

Just four months previously, Cherenkov had shone on the European stage, scoring twice - including a dramatic last-minute winner - as Spartak eliminated Aston Villa.

According to reports, Villa were so impressed they attempted to sign the 24-year-old midfielder. They would have known all too well the Soviet establishment would never allow their footballers - let alone major figures such as Cherenkov - to move to the West.

Overall, 1983 had been a phenomenal year for Cherenkov. Undeniably the best footballer in the country, he won the Soviet Union's player of the year award, even though Spartak finished second in the league. He was an important figure for the national team too, and scored twice in a 5-0 demolition of Portugal in qualifying for the European Championship.

That rise brought new levels of pressure.

"The psychological burden on him was probably too heavy," says Sergey Rodionov, Spartak's star striker of the 1980s, and Cherenkov's closest friend.

Those who witnessed the frightening scenes in Tbilisi don't like to talk about them. Cherenkov experienced hallucinations, visions of imaginary dangers, and even attempted to jump out of a hotel window.

Spartak coach Konstantin Beskov knew he wouldn't be able to play against Anderlecht. Cherenkov didn't understand why he was dropped.

Rodionov scored a late goal in a 1-0 win, but it wasn't enough and Spartak went out 4-3 on aggregate. But defeat was the last thing on the players' minds.

Cherenkov's health worried them. Upon returning to Moscow, he was immediately taken to hospital, and only returned to the pitch in June.

What was he suffering from? Nobody knows for sure, but it didn't go away, and visits to hospital became frequent. It would shape the rest of his career, and be part of his life until the very end.

"Fyodor had periods of depression and stress, but we never fully understood the nature of those problems. Geniuses can't be diagnosed. We can only guess," Rodionov says.

That word - genius - is universally used by those who saw Cherenkov play, and especially by those lucky enough to be his team-mates.

Cherenkov remains a beloved figure at Spartak especially, but he was widely admired

"He was a rare genius who could dribble, pass and shoot," says Vagiz Khidiyatullin, a defender in the Spartak and Soviet Union teams of the 1980s.

"His play was pure art. With every movement, he made life easier for his team-mates and harder for opponents. His intelligence was extraordinary."

Fans loved watching the thin and slender Cherenkov. He was perfectly suited for the inventive, short-passing style favoured by Beskov at Spartak.

The team had won the championship in Cherenkov's first full season in the starting line-up, in 1979. Ever since, he had defined Spartak. The supporters worshipped him.

But he also had a unique, wider appeal. Even those who despised Spartak loved Cherenkov. He was known as "the footballer of the people". His subtle, silky skills were irresistible, and his personality made him popular in every corner of the Soviet Union.

Good-hearted, generous, modest and shy, Cherenkov didn't fit the common template of a 'star' footballer. In fact, he never felt like a star at all.

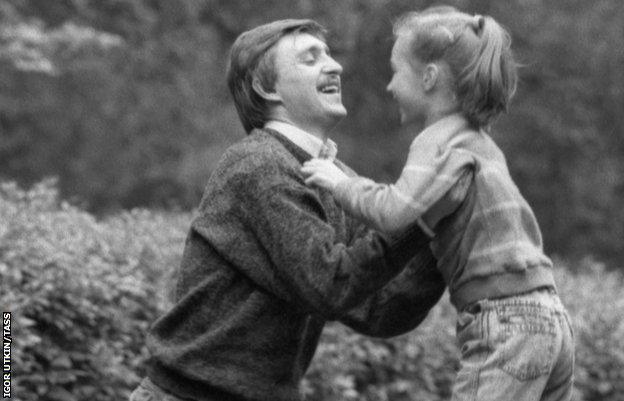

Cherenkov, pictured with his daughter Anastasia, who was born in 1980

"Fyodor always wondered: 'Why me? Why do they chant my name? Why do they like me so much?' He couldn't understand why he was so popular," says former team-mate Sergey Shavlo.

Cherenkov seemed to be a regular guy who just happened to be outrageously good at football. He was approachable and gentle, he never refused to be in a photograph, or sign an autograph. He liked to give gifts not just to family members and friends, but also to neighbours and strangers.

"Fyodor cared about people. His kindness really knew no bounds," Rodionov says.

Cherenkov's daughter, Anastasia, was a little girl during the '80s.

"I didn't understand my father's greatness, because he didn't behave like a star," she says. "When people stopped him in the street, he just talked to them quietly and politely. He hated compliments."

He was modest in the dressing room, too. An impression of fragility, though, could be misleading.

"Fyodor was very strong-willed," says Rodionov. "One might have been tempted to see his illness as an indication of weakness, but in reality it was exactly the opposite.

"Imagine how difficult it is to come back to the football pitch after a period of crisis in hospital and perform at the highest level.

"That's incredibly tough, both psychologically and physically - after missing so many training sessions. Yet Fyodor did it, time and time again. And he played brilliantly."

Widely seen as the best Soviet footballer of the decade, Cherenkov should have taken part in three World Cups but was left out in 1982, 1986 and 1990. He was omitted for Euro '88 as well, and thus remained relatively unknown outside his home country.

What was the reasoning behind the decision to drop him? Was illness to blame? It's impossible to say for sure. Rodionov says he would never talk about it. In 1982, his health was definitely not an issue.

There was another factor behind his absence. Did managers see him as a "risk"?

Cherenkov played his final match for Spartak Moscow in 1994

At the start of his career, Cherenkov's star had shone brightly in the national team. Aged 20, he scored in a 2-1 win over Brazil in 1980, a high-profile friendly celebrating 30 years of the Maracana stadium. Brazil fans were mightily impressed with his skills. It seemed he was destined for a major international career.

With Spartak coach Beskov, his beloved mentor, leading the Soviet Union's unusual three-man coaching team at the 1982 World Cup (alongside Dynamo Kyiv's Valery Lobanovsky and Nodar Akhalkatsi of Dinamo Tbilisi) Cherenkov would have been expected to walk into the squad. And yet he was left out.

After recovering from his first mental breakdown in 1984, Cherenkov became an integral part of the Soviet Union's plans for the 1986 World Cup, but again fell ill during a winter training camp in Mexico.

When then manager Eduard Malofeev was controversially replaced by Lobanovsky a couple of weeks before the tournament, it was obvious the coach would build his team around the Kyiv players he had just guided to an emphatic Cup Winners' Cup victory. Cherenkov could easily have fitted in, but Lobanovsky apparently had other ideas.

Fears over his condition might have played a part, Rodionov believes.

"It's a long tournament, and Lobanovsky's training sessions were notoriously intense," he says. "Altitude is high in Mexico, and that can be significant. Maybe Lobanovsky didn't want to take risks."

At Spartak, Cherenkov still flourished, especially in the odd years between major international tournaments, leading his side to a league and cup double in 1987, before winning the championship again in 1989 when he was also voted player of the season.

At the age of 30, the World Cup in Italy was his last chance of glory at a big tournament. But Lobanovsky again chose not to call him up, and 1990 was perhaps the bleakest year for Cherenkov.

That was also the year he chose to try his luck abroad, after the Iron Curtain fell. Fully understanding that life would be uncomfortable outside Moscow, Cherenkov only wanted to go on a new adventure alongside Rodionov.

Each received numerous offers separately, but strangely only Red Star of the French second division agreed to sign them both. Thus the great Soviet talent joined a tiny Parisian outfit totally unsuited to his level. His psychological problems became unbearable, and he returned to his homeland ahead of schedule.

Cherenkov died in October 2014 at the age of 55

In the twilight of his unique career, Cherenkov shone sporadically back at Spartak in 1991 and 1993, but spent all of 1992 out of football through illness.

Whenever he was fit and capable of playing, fans came to watch with smiles on their faces. He was still "the footballer of the people" and continued to be held in that regard even after his retirement in 1994.

Without football, Cherenkov disappeared from public life. He struggled with bouts of illness that became more and more serious, and attempted to take his own life on more than one occasion.

The public affection held for him was apparent for all to see when he died in October 2014, aged 55. He collapsed outside his home and was pronounced dead shortly after arriving at a local Moscow hospital. An autopsy found a brain tumour.

Thousands and thousands of people went to his funeral, and not only Spartak fans. Those in attendance wore the scarves of Zenit St Petersburg, CSKA Moscow or Dynamo Kyiv, for Cherenkov united the nation. He was more than just a football star. He was a true symbol of his era. Nobody - not even the great goalkeeper Lev Yashin - was adored so sincerely by so many.

"I only fully understood the amount of love people had for my father after he died," says Anastasia.

"People came to me and said part of their soul had died with him. They continue saying that even today. It is very touching. I am so grateful to them that they remember him."

Rodionov says: "Fyodor continues to live in people's hearts. He gave people light, and light came back to him.

"He enjoyed playing football, even if it was difficult at times. Every touch of the ball was the best cure for him. He was a genius with a tragic fate."

If you or someone you know has been affected by a mental health issue, help and support is available at bbc.co.uk/actionline