Parachute payments and the 'yo-yo' club phenomenon between the Premier League and Championship

- Published

Stefan Johansen and Tom Cairney scored when Fulham last played Norwich in 2018

Friday, 30 March 2018. In the pouring rain in Norfolk, goals from Stefan Johansen and Tom Cairney secure a 2-0 win for the visitors at Carrow Road.

This is the last meeting between Norwich City and Fulham - two clubs who have been each other's mirror image ever since.

Current Premier League players Ryan Sessegnon, now at Tottenham, and James Maddison, of Leicester, featured that day but, since then, Fulham have gone on a journey of five consecutive promotions and relegations, while Norwich have spent the past four seasons alternating between the top two leagues.

While one glided through the country's second tier the other fought, toiled, flapped and failed in the top flight - as they alternately "yo-yoed" between the two leagues.

Switch. Repeat.

This is part of a wider trend that has become apparent since parachute payments were introduced in 2006, a series of solidarity payments made from the Premier League to stabilise clubs in the first three years after relegation while they adjust to lower revenues.

It is a system used in all of Europe's top five leagues except in Germany,where Bundesliga and 2 Bundesliga clubs share a joint TV broadcast deal.

"The phenomenon of yo-yo clubs is definitely real," says football finance expert Dan Jones.

"The phenomenon of there being a huge cliff edge between the Premier League and Football League is very real.

Millwall chief executive Steve Kavanagh says the club cannot compete financially with those receiving parachute money

"And then the question becomes - if a team is going off a cliff edge, is giving them a parachute the right thing to do? And if you do, does it double up the trampoline and spring them straight back up again? The evidence is: sometimes, but not always."

The payments are calculated as a percentage of money earned by the Premier League and at the moment roughly equate to £41m in the first season following relegation, £34m in the second season and £16m in the third, according to football finance lecturer and author of The Price of Football, Kieran Maguire.

In the first seven seasons of parachute payments - up to 2012-13 - Birmingham City were the only club to be relegated from the top tier twice.

Some clubs 'take a holiday in the Championship'

Subsequently up to now, that number has grown to 12 teams and Norwich have been relegated four times - including in their past three Premier League seasons - while Watford, West Bromwich Albion, Burnley, Hull City and Fulham have all suffered three relegations since parachute payments began.

Since 2013, nine of the 27 relegated clubs have bounced back with immediate promotions, while 12 of the 27 promoted teams in that period have gone down in their first year.

Maguire, who is also the co-host of The Price of Football podcast, says "it could be argued we have a 24 or 25-club Premier League and some of them are just taking a holiday in the Championship", and this can be put down in part to his "rule of three".

"It's partly due to the way money is distributed in the Premier League itself. Promoted clubs are going to start off on a negative compared to not just the big six clubs [but the rest of the teams in the league]," he says.

"The 'big six' in the Premier League earn on average three times the revenue of the other 14.

"The other 14 clubs in the Premier League earn roughly three times the revenue of clubs who get parachute payments. The clubs who get parachute payments get three times the revenue, on average, of the other clubs in the Championship. The other Championship clubs get approximately three times the revenue of the clubs in League One."

Maguire believes parachute payments are currently too high and could be reduced by up to one third in value.

Brentford begin their second season in the Premier League away to Leicester on Sunday, 7 August, after finishing their first top-flight campaign in 13th.

The west London club beat Swansea at Wembley to earn promotion in 2020-21 and have not yet benefitted from any parachute payments.

While in the Championship, the Bees were at "a big financial disadvantage" to then-former top-flight teams such as Aston Villa and Newcastle, says director of football Phil Giles.

Championship clubs generate roughly £7m a year in TV money, Maguire says - £34m less than the three relegated clubs from the previous season.

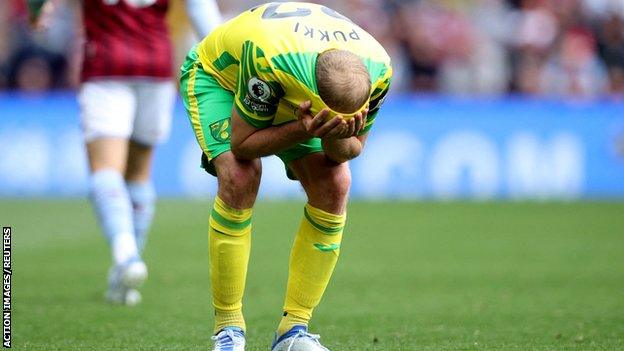

No team has been relegated more times from the Premier League than Norwich City [four] since parachute payments were introduced in 2006

"On the one hand I understand it [having parachute payments] because what you don't want to see is clubs going under and having their money cut so drastically that they're struggling to exist and no-one wants to see football clubs going out of business," says Giles.

"What you don't want to see is clubs then being put at an artificial advantage, where it's not really being used for what it was intended for. But actually it's allowing clubs to go and spend a lot more money on transfer fees and new players to help them bounce back up to the Premier League.

"It's that element of unfair competition, I think, is potentially the issue."

Giles, who has been at the club for seven years, says Brentford are halfway through a two-year strategy to cement themselves as a mid-table Premier League club but admits provisions such as relegation clauses in player contracts have been put in place.

He believes the parachute payments could be phased out over a long period if established Premier League clubs had enough time to prepare for the eventuality.

"Another way is allowing parachute money but only for certain purposes to make sure they are genuinely stopping clubs from struggling, as opposed to outspending their competitors," he adds.

"There is a bit of a pattern of teams going down and coming back up fairly quickly, so it does seem that there's a bit of unfair competition there and it's tough for teams in the Championship."

'Some clubs look to work between their means - many don't'

Another proposal that has been pitched by the EFL is scrapping parachute payments altogether and pooling money with the Premier League, which would see 75% of the funds go to the top tier and the remaining 25% be distributed in the EFL., external

This has similarities to one the EFL rejected when the Premier League was first created 30 years ago, Maguire says.

This has the backing of Millwall chief executive Steve Kavanagh, who believes the scheme would "make the league much stronger, fairer, and competitive".

Millwall finished ninth in the Championship last season, taking their play-off push to the final day of the season.

"Research suggests that over the last five years clubs who receive parachute payments are three times more likely to earn promotion than those who don't, so that tells you all you need to know about the impact on the competitiveness and fairness in the division," Kavanagh, who was recently elected on to the EFL board, says.

"Millwall, just as an example, will receive £40m less than a parachute club. How can we adequately compete with that?

"Some clubs - like ourselves - will always look to operate within their means but many don't, which is a result of the climate within which they're trying to achieve success."

In a letter to culture secretary Nadine Dorries, external in April, Premier League chief executive Richard Masters said the organisation was due to review the parachute payments system.

"It is our view that it is not as simple as more money to the EFL automatically leading to greater sustainability," he wrote.

"We know from experience this is not the answer. However, collective reform, paired with new and robustly enforced financial controls, is the right way to address the current challenges.

"We need the EFL Championship to continue to produce competitive teams that thrive when promoted to the Premier League and we need many teams in the Premier League vying for the top places and aspiring to European competition."

Much of the debate around the relevance of parachute payments focuses on financial sustainability against competitive balance.

"I think that the most important of those two is the financial sustainability and the reason that I think that is because, if you look at the trauma of a Bury or a Macclesfield, where the club is completely lost to the community, that is a bigger and worse trauma than the playing field being uneven in terms of final league position," Jones, formerly of Deloitte says.

"The preserving of the clubs, making sure they're there for the next generation, is the most important thing to me.

"In terms of the risk of the Championship getting too predictable, the competition is strong enough to cope with that. Whether that was Brentford getting promoted or, this season, Luton's performance in getting to the play-offs, you've still got drama going down to the last day of the season, you've still got drama through the play-offs.

"Again in the Premier League, you've got the relegation battle [Everton, Burnley and Leeds], Champions League battle [Tottenham and Arsenal] and a title battle [Manchester City and Liverpool], excitement, uncertainty, jeopardy - it's not dull or predictable."

English football may never be dull, but if the same teams keep getting relegated and promoted every year, it might just get predictable.