Ronaldo: The road to redemption with Brazil at the 2002 World Cup

- Published

In the fifth and final instalment of BBC Sport's World Cup icons series, we explore Ronaldo's Golden Boot-winning redemption with Brazil in 2002.

The kneecap exploded. It was lodged above his muscular right thigh. Team-mates donned in blue and black stood hands on head in disbelief.

The comeback had lasted just six minutes.

There was a collective, anxious intake of breath. Was this the end of the game's most devastating forward?

Two years later, as the ball nestled into the corner of Oliver Kahn's goal with the same ruthless precision that characterised a whole career, Ronaldo's response was a resounding 'no'.

Brazil were world champions. The frenzied celebrations rippled around Yokohama's International Stadium, through a delirious Rio de Janeiro and via millions rejoicing in front of their television screens at home.

Il Fenomeno had silenced the critics and seemingly defied science.

He had not only overcome the injury problems that threatened to derail him at Inter Milan but also exorcised the demons that lingered from Selecao's World Cup final defeat against France in 1998, when their star man suffered a seizure before the game.

Ronaldo had reclaimed his throne as the greatest among football's pantheon of goal-getters and his iconic grin, like his dazzling feet, lit up TV screens around the globe.

"He was fantastic, amazing," Brazil team-mate Cafu tells BBC Sport. "It showed the mental strength Ronaldo has to overcome the problems. It has been the story of his life."

The Brazil squad of 2002 have a WhatsApp group called 'Penta'.

Twenty years on from victory in Japan and South Korea, Cafu still messages daily as they reminisce about the nation's fifth world title. For Ronaldo, it is a welcome reminder of his redemption.

The rise was stratospheric.

After scoring 44 goals in 47 games in his first two seasons at Cruzeiro, Ronaldo went to USA '94 as a 17-year-old still bearing braces. He did not play a single minute, instead celebrating like a giddy kid waving an inflatable banana in Pierluigi Casiraghi's Italy shirt following Brazil's penalty shootout win in the final at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena.

A move to Europe, on the advice of team-mate Romario, followed and paved the way for a relentless goalscoring spree with PSV Eindhoven.

"You could tell straight away he had a certain thing about him," explains former team-mate Boudewijn Zenden, who would hang out in Ronaldo's penthouse and even bought a Portuguese For Dummies book so they could communicate better.

"He was lightning fast and any goalscoring opportunity, the one-on-ones, he always scored.

"There was only one way and that was towards the goal, always with pace and always with a good finish. He had tricks and could dribble anybody, but it was always clinical and lethal."

Off the pitch, he was always good fun and Zenden remembers dressing his mate up as a clown on a visit to Maastricht Carnival.

"As soon as he started smiling, everybody recognised him!" laughs the Dutchman. "He was a really nice guy, always with a smile on his face, always in for a joke."

When it came to football, though, Ronaldo was deadly serious.

Asked by a reporter how many goals he would score in his first season in the Netherlands, he said without a blink of an eye: "32."

"The journalist started laughing," recalls Zenden. "But Ronaldo didn't find it funny."

Ronaldo scored 32 domestic goals that season - 35 in 36 games when you add the scintillating hat-trick against Bayer Leverkusen in the Uefa Cup to his tally.

Now the press weren't laughing, they were completely captivated. So were PSV fans, belting out his name, while pundits gawped at this teenage phenomenon.

Ronaldo's upward trajectory continued from PSV to Barcelona in 1996 for a world-record £13.2m, where he scored 47 goals in 49 games in one season - many of such bewildering solo quality he alone was worth the entrance fee.

He was crowned the world's best player before another record transfer in 1997, this time to Inter Milan for £19.5m. A second world player of the year award and a Ballon d'Or followed.

"You cannot give him one chance because he will score," adds Zenden. "That is his power. If you lose him out of sight, you are dead."

Aged 17, Ronaldo was an unused member of Brazil's 1994 World Cup-winning squad

Just four years after he warmed the bench in the California sunshine, Ronaldo arrived at France '98 as the most complete forward in the world.

"He was a constant danger," remembers former Brazil team-mate Savio. "A player with a lot of talent, a lot of capacity, a lot of resources in the field and - history tells us all - the best nine in football history. Phenomenal!"

He'd already scored a wonder goal in Paris a month earlier as Inter beat Lazio to win the Uefa Cup and then lit up the first six games of the World Cup to be awarded the Golden Ball. But it is the dramatic build-up to the final and his forlorn performance at the Parc des Prince that is remembered.

Ronaldo woke from his sleep after the team lunch to be told he'd had a seizure, been unconscious for two minutes and would not play that evening.

Cafu was one of the first to his hotel room after the convulsions: "We were very worried because he was one of the key players of the team. He didn't travel with us on the bus, he went to the hospital and then came directly to the stadium."

Ronaldo convinced the medical team to do fitness tests but it was not until shortly before kick-off head coach Mario Zagallo was persuaded the forward was fine to start.

In the home dressing room, Lilian Thuram and his France team-mates were convinced it was a ploy.

"We thought 'no way, Ronaldo is playing, they are just making this up to try and fool us'," the defender remembers.

"In games like this, small margins and how a player is feeling can make a difference.

"Who knows, if Ronaldo had been at 100% of his abilities and feeling well, maybe Brazil would have won?"

Little did Ronaldo know things would get worse before they got better.

Brazil, without Ronaldo at his best, lost 3-0 to France in the 1998 World Cup final in Paris

Medical staff in Milan marvelled at Ronaldo's ferocious physique. Powerful, nimble, the fast-twitch fibres of a cheetah. They calculated he could run 100m in around 10.2 seconds. He could collect the ball deep, swivel and turn defenders' legs to jelly with his rapid change of pace and direction. The Brazilian was redefining what it meant to be a centre-forward.

But Ronaldo's unprecedented physical armoury was also his weakness. He was explosive to the point his body could erupt, and suffered from instability between the kneecap and femur.

In November 1999, he ruptured a tendon in his right knee and needed surgery. Five months later, during his return in the first leg of the Coppa Italia final against Lazio, it went completely.

Ronaldo was only on the pitch six minutes when he shaped to execute one of his iconic step overs, but instead his leg gave way - tendons ripped, kneecap displaced, the seemingly indestructible phenomenon agonisingly reduced to a howling heap on the Stadio Olimpico turf.

One Inter physio said it was the worst injury he'd ever witnessed, another suggested Ronaldo needed a miracle. Even two years out from Japan and Korea, his World Cup hopes were in serious doubt.

And, boy, there were doubts. From doctors, from Ronaldo, from the media, from fans who worshipped a player they truly believed was on the path to becoming the greatest of all time.

Eight months into his recovery, Ronaldo still could not bend his knee beyond 90 degrees. He questioned whether the science existed to fix him and travelled the globe in search of answers, the birth of his son Ronald giving him the strength to endure what he called "endless torture" as eventually he underwent a procedure to gain more flexibility.

It meant almost nine hours of rehabilitation work every day.

Through October and November 2001 there were sporadic appearances as Inter managed him back to fitness, only for a hamstring injury to rule him out until the end of March - two months before the World Cup.

Ronaldo was a favourite among Brazilian fans at the World Cup

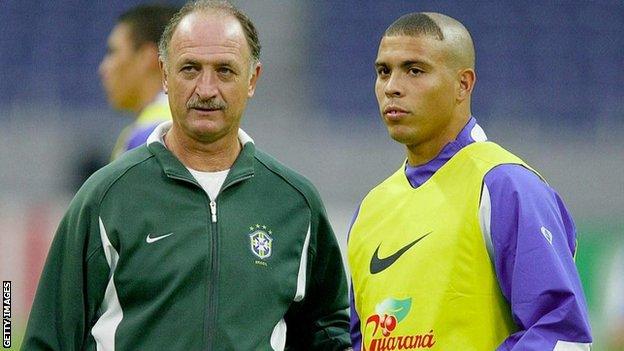

Brazil boss Luiz Felipe Scolari immediately showed his faith by handing Ronaldo 45 minutes in a friendly win over Yugoslavia, and the forward returned to Serie A to score four goals in the final five games of the season.

He emerged from the gloom of a nightmarish two years determined to shine on the world's biggest stage that summer.

"Ronaldo wanted to show he had the capacity to overcome the problems," says Cafu. "There were no other bad feelings about it, just the will to face what had happened and overcome it."

As the tournament edged closer, fans' appetites were whetted as Ronaldo joined a cast of the world's best players in Nike's secret cage football advertising campaign to the tune of Elvis Presley's A Little Less Conversation. The manufacturer obviously backed their star charge to be fit.

Nike might as well have invited only the Brazil squad, such was the plethora of entertainers they had in a summer that would prove something of a last samba for the creativity of South America's canary-clobbered trendsetters.

Ronaldo, Rivaldo, Denilson, a young Kaka, the biggest trickster of them all in Ronaldinho, not to mention marauding wing-backs Cafu and Roberto Carlos. But the feeling in Brazil was these players were being stifled by Scolari's excessive discipline.

It wasn't just Ronaldo who was left scarred by '98. The conspiracy theories that followed triggered a parliamentary inquiry, where the forward was called as a witness. One congressman even brought his son along for an autograph.

Brazil had also blitzed through three coaches between tournaments before landing on Scolari, with their World Cup qualification in jeopardy. Despite dragging them through, he was despised back home by the summer of 2002.

Accused of disrespecting the 'sovereignty' of the iconic yellow jersey for wanting to play in Brazil's changed blue shirt, car attacked for not selecting veteran striker Romario, vilified for his style of playing with three central defenders - the boss had more headaches than just trying to squeeze all that talent into one functional XI.

Then, the day before Brazil's opening game against Turkey in South Korea, captain Emerson was ruled out of the tournament after injuring his shoulder playing in goal during training.

After consulting the team psychologist, Scolari decided on a leadership group where Cafu took the armband and Roberto Carlos, Roque Junior, Rivaldo and Ronaldo also had input.

The manager may have lost the Brazilian people but he had won over the players who had initially found him cold and tough. Now they called him 'Dad' or 'General Big Phil' and bought into the 'Scolari family' idea.

Juliano Belletti even captured the trip on his handheld camcorder like it was a home video, the footage of which can be watched in Sky documentary Brazil 2002: The Real Story.

Luiz Felipe Scolari put his faith in Ronaldo being fit for the World Cup in 2002

An attacking triumvirate of the three Rs - Ronaldinho, Rivaldo and Ronaldo - started the opener against Turkey, but Brazil were tense and the Turks tough, taking the lead in first-half stoppage time through Hasan Sas.

There were calls for calm in the dressing room at the break. Then Rivaldo whipped over a cross from the left and Ronaldo threw himself at it, guiding the ball beyond goalkeeper Rustu Recber.

Confidence began to ooze through the 25-year-old and moments later he was the youthful Ronaldo bursting into the world's consciousness again, bumping off one defender, bamboozling another with a trademark step over and then forcing Rustu to save. Rivaldo's late penalty completed the turnaround. Brazil were in business.

"This is just the start," Ronaldo told reporters afterwards. "I hope more goals and moments like this come my way."

And they did. One in the 4-0 thrashing of China, where Ronaldo arrived late to turn in a Cafu cross, before a double in the 5-2 defeat of Costa Rica in the final group game in Suwon.

Ronaldo's eight goals as Brazil win 2002 World Cup

Behind the scenes, Scolari's team prepared meticulously. Every detail from logistics to individual medical plans, to someone sitting with Ronaldo at lunch and dinner to make sure he was eating correctly for the tournament.

Brazil's entourage took over a whole hotel floor and played table tennis, pool and video games to fill the hours. There was bingo at meal times. It was two months cut off from the outside world and the big question from the press was whether players were managing to have intercourse.

"You mean with each other?" quipped Scolari. "I don't think so."

"That sacrifice we committed to - it was such a long time," recalls Ronaldo in Brazil 2002: The Real Story. "I think it was irresponsible of us to make such a promise. Some journalists sent us adult magazines - Big Phil took them all and went to the press: 'Don't you send my boys these again, we're working hard here!'"

They headed to Kobe in Japan for a last-16 meeting with Belgium, where Brazil were fortunate rather than majestic as Marc Wilmots' opener was controversially ruled out.

It took a moment of brilliance from Rivaldo to put Scolari's side in front and Ronaldo, who had promised a goal in every game, delivered again late on with a first-time left-footed finish from Jose Kleberson's pass that squeezed under goalkeeper Geert de Vlieger.

England players watched in the stands at the Kobe Wing Stadium, knowing they would face the winners.

It was a Three Lions team Ronaldo ranked as England's best of all time, the Golden Generation, and he singled out having to face defender Sol Campbell.

"R9, Ronaldo, was just the best. You knew he was on fire and you had to play good football to stop him," Campbell, who almost joined the Brazilian at Inter in 2001, tells BBC Sport. "You had to be on your toes all the time. I loved that challenge.

"He had absolutely everything, he was still amazing after his injury - imagine if he didn't get injured?! He was unbelievable. Defenders and goalkeepers were so frightened of him. He was incredible."

Brazil's 2-1 win over England was the only game of the tournament in which Ronaldo did not score

"We played Brazil in the hottest part of Japan," explains Campbell. "The day before, it was pouring down with rain and we were thinking 'is this going to last?'. I spoke to Gilberto [Silva] and he said Brazil were praying for sun, but we were praying for rain! It was so hot. The humidity and heat were unbearable."

Michael Owen pounced on a Lucio mistake to put England in front early on, but the call from captain Cafu was "calma, calma".

The Brazilians were not fazed in the Shizuoka sunshine. David Beckham remembers spotting Ronaldo and Roberto Carlos laughing together in the penalty area during a break in play and fearing the worst.

The pair were room-mates, it had been that way since 1993. Ronaldo would kiss the pocket rocket's head before games to unleash a 'superpower'. On that day, it was Ronaldinho who possessed the super-human touch.

The Paris St-Germain maverick screeched past Paul Scholes over the halfway line, threw Ashley Cole out of his path with a deft step over and was faced with a three on two as he approached the box. With Ronaldo's run creating space to his left, Ronaldinho shifted it right towards Rivaldo and he stroked in left-footed for the leveller on the brink of half-time.

Five minutes after the break came the free-kick. Surely from that angle and distance Ronaldinho would look for a team-mate? Instead his effort looped over David Seaman and into the far corner.

"An incredible free-kick," says Ronaldo. "We thought he was crossing. He keeps saying it was on purpose, that he meant to put it there!"

Scolari rejoiced at the final whistle. When Brazil qualified for the World Cup he made the almost 20km pilgrimage from his home in Caxias do Sul to Farroupilha. Now his team, even after Ronaldinho was sent off for a foul on Danny Mills, were marching into the semi-finals.

"They had a fantastic team and we had our chances, but we just didn't capitalise on it," adds Campbell. "They didn't have many chances, other than the free-kick and Ronaldinho opening us up. That's how close we were to beating them, they just had a little bit more quality and individual skill."

There was unity in the Brazil camp. Reserve players wanted to propel their first-team rivals to greatness. On the bus to games there was samba, tambourine sound, Roberto Carlos dancing in the aisle and Ronaldo banging on the window with a clenched fist, toothy grin beaming from beneath his national team baseball cap. The same playlist as they ticked off win after win.

It was a group of players having fun, easing the pressure as the focus on Brazil intensified. Hundreds of journalists attended their training sessions and fans scrambled for a glimpse.

Ronaldo, though, was carrying a thigh injury and was a doubt for the semi-final against Turkey. It was the major talking point as the game in Saitama drew closer. Then the forward took a razor to his scalp, leaving a now notorious patch of hair at the front.

"I thought: 'That is very ugly!'" laughs Cafu, who was among the team-mates to tell Ronaldo to cut it off. After being papped during training, the haircut became front-page news.

"I got many complaints from kids' mothers because it was a craze in Brazil," admits Ronaldo. "But it was good to distract everybody's attention from my injury."

The game was tense, tight and then Ronaldo sparked into life. Dropping a yard off his marker to receive a pass from Silva on the edge of the attacking third, his first touch was towards the touchline, sucking defender Bulent Korkmaz in and propelling beyond him into the penalty box.

The angle was narrow as Ronaldo glanced towards goal, the thigh injury in the back of his mind, and with that he opted for a toe poke.

This was the boy named after the doctor who delivered him in exchange for three kilos of shrimp back playing futsal in Bento Ribeiro, jabbing the ball along the turf towards the corner with enough power that Rustu could only help it into the net.

"It was the only non-painful thing I could do," recalls Ronaldo, who was reduced to tears as Brazil sealed an emotional return to the World Cup final, the letters of his name held aloft Hollywood-style by fans in yellow and green bouncing in the stands.

At midnight on the eve of the final, Scolari found a handful of his squad playing golf in the hotel corridor. They seemed relaxed. Come game day, though, the memories of 1998 resurfaced for Ronaldo.

He didn't take his usual pre-match nap - the moment the seizure had struck four years earlier - instead seeking out back-up goalkeeper Dida to chat until the bus left for the stadium.

In the team meeting, Scolari played a video tape of Brazil's highlights, interspersed with fans praising their heroes. Juninho Paulista and Vampeta fought back tears, while for Ronaldo it presented a third and final battle to overcome on his road to glory - the trauma of '98, his horrific knee injury and now the responsibility of uniting the Brazilian people.

Japanese emperor Akihito's presence in Yokohama meant the squads and officials had to arrive extra early. Referee Pierluigi Collina made small talk with Ronaldo and once out on the pitch Vampeta broke from tournament tradition by leading all the substitutes into the pre-game photographs.

Germany goalkeeper Oliver Kahn was named the tournament's best player beforehand and denied Ronaldo early on. The Brazilian helped him up, gave his rival a pat on the bottom and cast a look that suggested he was not finished yet.

Khan was faultless throughout the competition, right up to the 67th minute of the final, when he spilled Rivaldo's shot into the path of Ronaldo to hand the predatory Brazilian a tap-in.

The finish was simple, but Ronaldo's brutish strength and determination created the chance in the first place, bundling Dietmar Hamann off the ball to recover possession, slipping it to his team-mate and continuing his run in anticipation of a rebound.

If the first was instinctive, the second was world class. Kleberson made a break down the right, Rivaldo dummied at the top of the penalty area and Ronaldo's cushioned touch teed him up perfectly to stroke the ball into the bottom corner for his eighth goal of the tournament.

He sprinted - arms outstretched, tuft of hair protruding from his forehead like a five o'clock shadow - towards the bench to be embraced in the knowledge Brazil were world champions.

Once again, just like four years earlier, Ronaldo was crying by the final whistle. This time with relief and elation.

Amid the post-match party of samba and drums, the Golden Boot winner was the last Brazilian into the media room to talk to the press, where he was asked if this was a better feeling than sex.

"Both are very hard to go without," giggled the forward. "But I don't think sex could ever be as rewarding as winning the World Cup."

It speaks to Ronaldo's character that the surgeon who operated on his knee was in the crowd that day as one of the forward's guests.

"I'm slowly realising just what happened," Ronaldo continued afterwards.

"My happiness and my emotion are so great that it's difficult to understand. I've said before that my big victory was to play football again, to run again and to score goals again.

"This victory, for our fifth world title, has crowned my recovery and the work of the whole team."

For Ronaldo, the road to redemption was complete.

BBC World Cup icons series