Craig Brown: 'The affable & gregarious charmer who never got due appreciation'

- Published

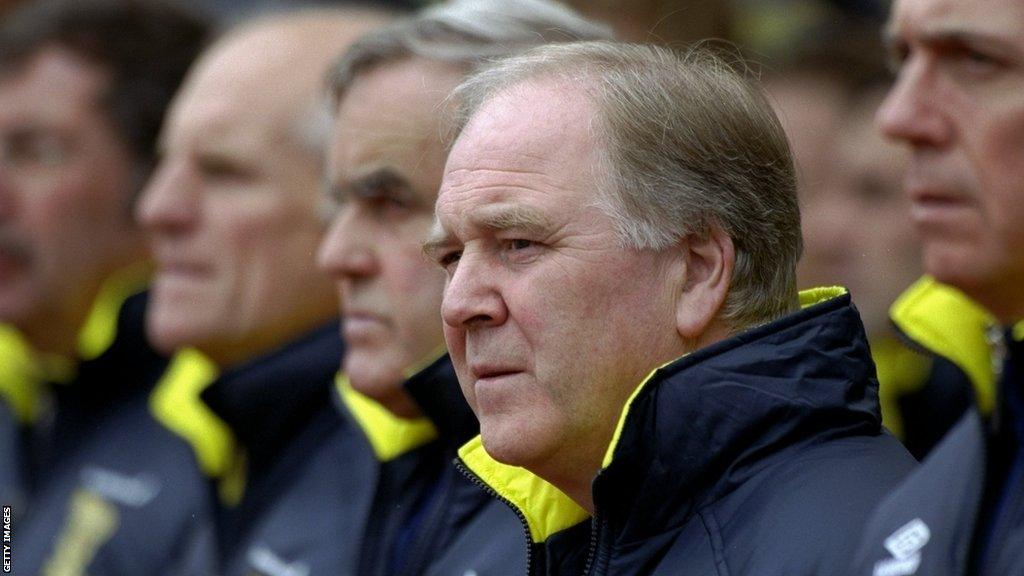

Craig Brown managed Scotland at two major tournaments and was an assistant at a further two

It was only supposed to be a coffee, a quickish chat for an upcoming feature about a Scotland qualifier, but Craig Brown never did quickish chats. Once you had him, it was hard to let go of him.

The stories flowed. His recollections of training with Billy McNeill as kids at Celtic; his frustrations of signing for Rangers at 17 but never playing; his cameos in Dundee's famous championship-winning season of 1961-62 and the injuries that destroyed his time as a footballer; the yarns about his great coaching influence; Motherwell's Willie McLean - brother of Jim; Jock Stein, Bill Shankly and his brother Bob, Alex Ferguson and onwards.

By the time we were done, there was a parking ticket on both our cars. Two hours paid for, we were in there for three and a half.

Wee Broon had time for everybody. He was a relentlessly positive man even when surrounded by wholesale negativity.

He was warm and gregarious, an affable character, a total charmer, an underdog who never really got the appreciation he was due having managed Scotland in more matches than anybody else in history. A product of the Largs coaching school, he remains the last person to take the men's national team to a World Cup.

He was at the heart of most of the buzz that Scotland has experienced on the big stages in the 1980s and 1990s. He was Ferguson's assistant at the World Cup in Mexico in 1986 and Andy Roxburgh's assistant at the World Cup in Italy in 1990 and at the Euros in Sweden in 1992.

Having managed the Scotland Under-16 side to a World Cup final in 1989 - it's almost trippy to think about it now - and the Scotland Under-21s to a European championship semi-final in 1992, the top job was his when Roxburgh went.

He wasn't sure he was going to get it. "I thought I had become invisible," he said. "Everybody's name [Kenny Dalglish, Gordon Strachan, Joe Jordan, Ferguson] was mentioned but mine." The SFA chose wisely.

As a manager, Brown was an intelligent pragmatist with a personality to convince his players that they should fear nobody. "He was ahead of his time in terms of his preparation, how he managed people and the psychology of dealing with the opposition," said Davie Weir, one of his key men along the way. "You were never intimidated by anyone."

For much of his time in full-time charge - 70 games across eight years with only nine competitive losses from 26 matches - Scotland were organised and driven.

When he took Scotland to Euro '96, they only conceded three goals in 10 qualifying games. When they made the World Cup finals in 1998, again, they only conceded three times in 10 group matches. In qualifiers or tournament play, his side went on an extraordinary run of 14 clean sheets in 15 games.

Brown was loveable and approachable, but there was a serious football intellect there, a huge hunger to take it to the big guns.

"What comes through the years is an inner hardness and a determination to make your own decisions," he said in The Management, a book about Scotland's great football bosses. "You have to be single-minded and autocratic.

"There seems to be a measure of democracy creeping into the dressing rooms, but I am of the old school. Whatever I say is the way it must be. And then I will face the consequences of my own actions."

If the defining moment of his Euros in 1996 was Paul Gascoigne's goal and Gary McAllister's penalty miss at Wembley, then it was the Brazil game that opened the World Cup in 1998 that will live forever in the memory. A packed Stade de France and the eyes of the football world on Scotland. It's never been that way since.

It was 1-1 with 16 minutes to go. Brown's tactics had kept out Cafu, Roberto Carlos, Rivaldo, Ronaldo and Bebeto. A famous draw was at hand, only for Tom Boyd (one of Brown's key lieutenants at the back) to unluckily knock the ball into his own net.

A 3-0 loss to Morocco did for the Scots that summer. Decades later, Brown still trotted out the stats from that game, still railed that the scoreline did not reflect the flow of the game.

He got monstrous stick for that Morocco debacle but he drove on, always cheery, always believing, even when the results started to go downhill.

He made the play-offs for Euro 2000, lost 2-0 to England at Hampden before famously beating them 1-0 at Wembley. The irony of possibly his greatest ever victory coinciding with one of his biggest disappointments was not lost on him.

When Scotland failed to make the play-offs for the World Cup in 2002, the criticism had grown ever louder and he was gone.

The end of his story? Not a bit of it. He managed Preston, Motherwell and Aberdeen after that. In a European game with Motherwell against Odense in 2010, there was a fracas on the sideline. The Odense director shoved Brown and Brown responded by thumping him. He was 70 and still up for the fight. Football kept him young, he said.

He loved proving people wrong, whether in his ability to take Scotland to major championships or to fly the flag for the old guard by managing into his 70s, or through his physical capacity to survive illness when the odds were seemingly stacked against him. Age was only ever a number to him, not a state of mind.

"Alex Ferguson would tell me I was the oldest manager in Scotland. 'Oh, am I?' Then he would say, 'Actually, you're the oldest manager in Britain'. Oh, am I? Then it would be, 'You're the oldest club manager in Europe'. I was 72 at the time. I said to him, 'How do you know?' And he said, 'I know everything'."

In 2020, he suffered a life-threatening aneurysm. "The two ambulance guys said to me, 'In the last three years we've had over 20 of these and only three have made it alive to the hospital'."

That was Brown. Defying convention and doing it with a story that put a smile on the face of everyone around him. He did that for most of his storied life. He will be very sorely missed by so many people.

Brown was part of Dundee's 1961-62 title-winning squad