Jules Bianchi: Ayrton Senna death a 'wake-up call' F1 never forgot

- Published

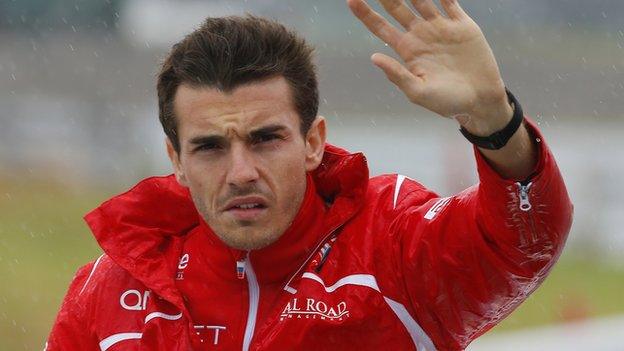

Medics at the scene treat Jules Bianchi during the Japanese Grand Prix

The horrific accident suffered by Jules Bianchi, who is fighting for his life in a Japanese hospital after crashing at Suzuka on Sunday, has re-focused attention on safety in Formula 1.

Within the sport itself, though, the quest to improve safety has never slackened since the death of Ayrton Senna in 1994, external led to a long period of self-examination, and an awareness that complacency had set in, to a degree.

Senna's death and the terrible weekend at Imola that preceded it - which included the death of another driver, Roland Ratzenberger - for a while seemed to be a threat to the sport itself, such was its global impact.

That was a wake-up call for whom those in charge of the sport's governing body, the FIA, have never forgotten.

The 20 years since Senna's death have seen a never-ending campaign to increase safety in F1, with advances in technology in every area.

Bianchi's accident was a shock to the whole sport. It will certainly lead to another period of introspection and analysis but it won't mark the sea-change seen after Senna. It can't, because the quest for safety has never stopped since.

These are some of the key advances in the last 20 years.

Barriers

Tyres have been used to cushion the impact of cars hitting the walls surrounding circuits for years. It sounds rudimentary, but years of research have proved they are very good at absorbing the impact of an F1 car at speed.

Key developments have aided the effectiveness of the Armco barriers used in F1

But two key developments have revolutionised their effectiveness.

The first was fixing the barrier to the ground to keep it in place to do its job of absorbing the extreme forces of an F1 crash.

The second was to 'belt' the barriers - basically, fastening them together with a strip of strong rubber. This made a significant difference in ensuring cars did not penetrate the barrier itself.

That hugely reduced the risk of cars torpedoing through barriers, risking injury to the driver's head when it came in to contact with the tyres.

In recent years, a new kind of barrier called TecPro has begun to be introduced. These are an outside casing of polyethylene metallic sheet with high-density foam inside.

These have practicality benefits over tyres,, external but there is not a huge difference in terms of their effectiveness in impact absorption.

Pit lane

Senna's death is the aspect of the dreadful weekend at the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix that is most remembered. But among the many horrific incidents was a collision in the pit lane that led to mechanics being injured by a loose wheel.

Since then, stricter pit-lane speed limits have been enforced, there have been limitations on the number of people who can be in the pit lane when cars are active on track - in the races, pit-lane reporters from TV companies are now no longer even allowed to move about - and the pit lanes have been 'zoned'.

The death of Ayrton Senna in 1994 led to a sea change in F1 safety

There are three - a 'fast' lane, an acceleration lane, and the pit 'boxes' themselves where the cars stop - and there are strict rules about when a team can release a car from a stop if another is approaching.

Retaining devices have recently been fitted to wheels to keep them in place as soon as they are seated on the axle, although the forces involved mean these are not always successful in keeping wheels attached to cars if they are not fitted correctly at a pit stop.

Cockpit

Look back at pictures of the cars of the early 1990s, and it is shocking how exposed the drivers' heads, necks and shoulders were.

Before the death of Ayrton Senna in 1994 drivers' head, neck and shoulders were exposed in the cockpit

Senna was killed by his front wheel bouncing back and a suspension arm piercing his helmet; Ratzenberger by a broken neck, external when his car slammed into a wall at close to 200mph. Since then, rule-makers have focused hard on protecting the drivers' heads and necks.

The first major step was the introduction of raised cockpit sides and padding in 1996, a development that has extended now to the cockpit sides having a mandated shape aimed at ensuring the best possible protection in an open racing car while not restricting the driver's view too much.

Since 1996, cockpits have been high-sided for proctection

By 1994, racing cars were already immensely strong, built as they were of carbon-fibre and Kevlar - Senna would have walked away unhurt from his 135mph impact had he not been unlucky enough to be hit by his wheel.

But the structure of the cockpit has since been strengthened, with a minimum thickness of the cockpit wall defined from 2000, as well as the introduction of a layer of Kevlar - used in bullet-proof vests - to prevent intrusion.

The ubiquity of electronics in F1 cars in the 21st Century has also allowed the FIA to install cockpit systems that improve safety, including the use of LEDs that correspond with the use of warning flags around the track and maximum speed limits for when the safety car has been deployed but the field has not yet formed up behind it.

Driver equipment

Neck injuries are among the biggest risks to a racing driver in a crash. His body is tightly belted in to an immensely strong survival cell, and his head is protected by a helmet but the neck remains vulnerable.

But a huge stride was made in neck protection with the adoption of the Head and Neck Support (Hans) device in 2003.

The development of the Head and Neck Support (Hans) device in 2003 has helped to reduce the likelihood of head and/or neck injuries in the event of a crash

This is a yoke-type structure that attaches to the helmet with straps and sits under the seat belts over the driver's shoulders.

The Hans device restrains the head during an impact and has dramatically reduced the risk of basilar skull fractures - a break of the base of the skull - which have killed many drivers over the years.

There have also been regular advances in helmet design. The most recent was driven by Felipe Massa's freak accident in qualifying in Hungary, external in 2009. The Brazilian suffered a skull fracture when he was hit on the helmet by a suspension part that had come off another car.

Designers face the conundrum that the helmet needs to be light - because extra weight puts more strain on the driver's neck - but also strong.

In 2011, a new standard was introduced, which features a skin of two layers of carbon-fibre and one of Kevlar on top of the fireproof absorbent foam on the inside, and the addition of a strip of a material called Zylon on the visor. It has a tensile strength 1.6 times higher than Kevlar and is said to make it essentially bullet proof.

The car

The first big change following Senna's death was the introduction of the underbody 'plank' to force the teams to raise the ride-height of the cars.

This prevented designers generating as much under-floor 'ground effect' - where speeded-up air produces a low-pressure area, sucking the car towards the ground.

The amount the 'plank' is allowed to wear is strictly controlled - if it reduces by more than 1mm in certain areas during a race, the car is disqualified.

A further step in this process is being introduced next year with the banning of the use of dense, heavy metals such as tungsten as skid plates.

From 2015 on, titanium - which wears much faster - will be mandated, which will force the teams to run their cars higher to ensure the plank does not wear too much. This will inevitably reduce downforce and slow cornering speeds.

Suspension is now designed in such a way as to break in the event of a wheel-over-wheel accident, the sort which used to launch cars with regularity in the 1970s and early 1980s.

In 1982, Ferrari driver Gilles Villeneuve was killed and his team-mate Didier Pironi's legs were smashed so badly he never raced again in two separate but alarmingly similar accidents when they hit the back of another car and took off, before somersaulting down the track.

Driver protection

The other huge development in car safety in this period has been the introduction of wheel tethers. These are cables that run through the suspension arms with the aim of preventing wheels becoming detached from cars during accidents.

As a bouncing wheel is a serious threat to both the drivers' exposed heads and spectators, this has significantly improved safety.

The death of Henry Surtees, the son of 1964 F1 world champion John Surtees, in a Formula 2 race in 2009 after being hit by a loose wheel led to a programme of research into additional cockpit protection for drivers.

The new car for Lotus's 2014 campaign

Various options were looked at, including fighter jet-style canopies, but the only one the FIA considered viable was a forward roll structure to deflect wheels.

It has emerged this week that senior F1 bosses, including Bernie Ecclestone, rejected the adoption of these at a meeting a year ago on the basis that they were unsightly and risked taking F1 away from its central ethos - of being for open-cockpit, open-wheel, single-seater racing cars.

But this concept could be revisited following the severe head injury suffered by Bianchi when his Marussia went under a tractor recovering another car.

It is far from clear, though, whether any such structure would have protected the Frenchman, given that the roll-over structure behind his head was very badly damaged in the accident. The same could easily have happened to one in front, given the forces involved

Crash testing

One of the single biggest steps in ensuring a single standard of F1 safety has been the introduction of crash testing.

They started in the early 1990s, but have grown ever more stringent, with front, side and rear impact tests of increasing severity.

For a long time, teams only had to pass these before the first race of the season, which meant they could test all winter with a car that had not been crash-tested.

But in a new development of the last couple of years, cars now have to pass these before they are allowed on to the track at all.

The Russian Grand Prix is live on BBC TV, radio and online.

- Published19 November 2014

- Published8 October 2014

- Published7 October 2014

- Published6 October 2014

- Published6 October 2014

- Published5 October 2014

.jpg)

- Published18 July 2015

- Published5 October 2014

- Published26 February 2019