Ron Dennis: How broken friendship led to McLaren exit after 35 years as boss

- Published

Ron Dennis received a CBE in 2000

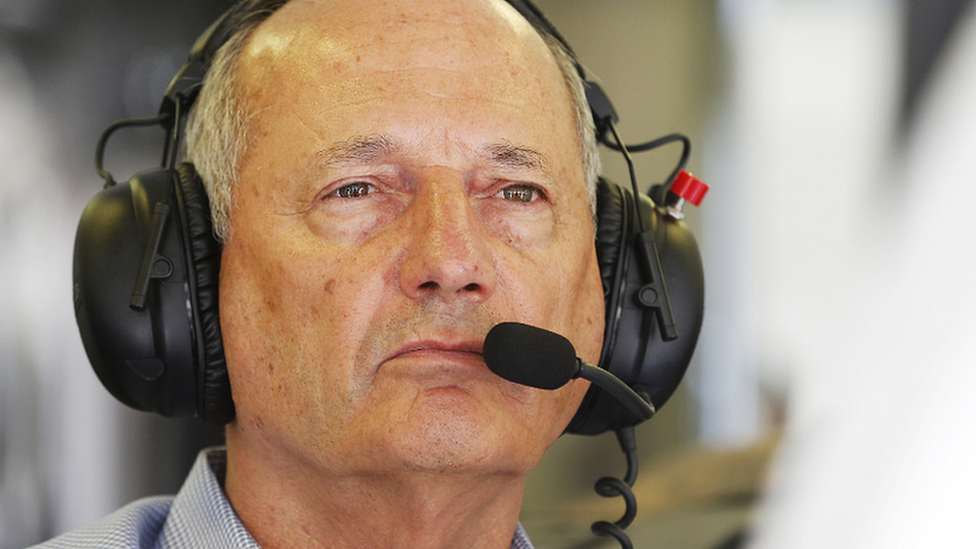

Ron Dennis has finally bowed to the inevitable.

When he was forced out of McLaren in November, Dennis went around telling people he would be back, that he would find a way to wreak revenge on the former friends and partners who had ended his reign at the company that was his life.

But that was never going to happen, given the power and wealth of the men involved.

Friday's announcement that Dennis had sold his remaining 25% shareholding in McLaren to those men and formally parted ways with the company was always going to be the result of that boardroom coup as winter closed in at the end of 2016.

Back then, Ron Dennis' departure from McLaren was no less shocking for knowing it was coming.

After all, this is a giant of both Formula 1 and British industry, who was forced out of the company he had built up - which had made him the most successful team boss in F1 history, which is now one of the world's leading sportscar manufacturers - by his own partners.

It is a story with many aspects of a Greek tragedy: a great but flawed man losing the thing he cares about most, at least partly because of his own failings.

At its heart is the story of a broken friendship - between Dennis and fellow shareholder Mansour Ojjeh, who were close allies for three decades before they fell out a few years ago.

Why? There are stories buzzing around the F1 paddock about it, including one that many of those close to the situation believe to be true but which cannot be detailed here.

One thing is clear, however. It got very personal between the two of them before Ojjeh finally won the battle.

In truth, it is not hard to see how someone could fall out with Dennis.

David Cameron, then the Prime Minister, talks to Dennis during a 2011 visit to the McLaren Technology Centre

Undoubtedly a brilliant man, he is also an intensely complex personality: generous and loyal on the one hand, gauche and arrogant on the other. He can also be disarmingly charming, amusing and self-deprecating.

Asked about the merit of the Norman Foster-designed McLaren Technology Centre, which opened in 2003 and cost hundreds of millions of pounds, he once offered: "Have I built myself a pyramid, you mean?"

And 20 years or so ago, he told a very funny story about his own well-known obsessive-compulsive tendencies.

It was about the new house he and then-wife Lisa had bought, in which fountains had been installed in the rose gardens. When these were first turned on, Dennis said, he was horrified to see that they came on row by row, instead of all at the same time.

This wouldn't do, he told the garden designer. They had to come on all at once. "But Mr Dennis," responded the designer, "it will cost thousands to start again, install all the necessary pumps and so on." Dennis said he didn't care. It had to be done. He couldn't look at it the way it was.

Yet his condescension and patronising attitude could take your breath away and he has made a lot of enemies along the way.

To journalists, he would publicly pride himself on his oft-repeated claim that he would be economical with the truth but not actually lie to you. Yet sometimes he did.

In the late 1990s, I had found out that Mercedes were about to buy a significant but still minority shareholding in McLaren and went to Dennis to verify it. "Who's your source?" he asked me. When I told him I would not reveal it, he said I should get a new one because this one was wide of the mark.

Two weeks later, he stood up at Silverstone and announced that Mercedes had bought a 40% shareholding in McLaren.

When he was challenged about it, he initially tried to claim I had asked the wrong question, before eventually conceding that, yes, he had lied. "I had to," he said.

At Silverstone last year, I asked him what would happen when his contract ran out in mid-January 2017. He said: "Oh, don't worry about that. I've signed for another two years."

Emergence of a ground-breaker

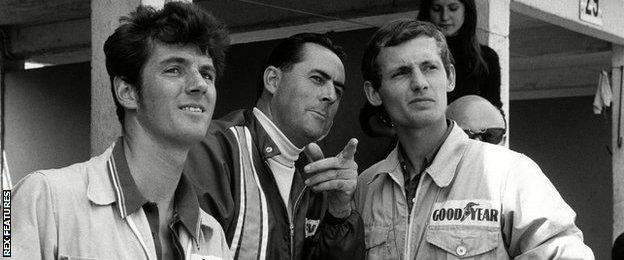

A youthful Dennis, right, talks to team owner Jack Brabham at the 1969 German Grand Prix

Dennis started his career as a mechanic for Jack Brabham in F1 in the late 1960s. After an abortive foray into F1 in the early 1970s, he set up a Formula Two team with backing from cigarette giant Marlboro.

Success there came as McLaren's F1 team - also backed by Marlboro - was becoming uncompetitive. The tobacco company engineered it so Dennis' Project Four organisation could take over McLaren.

Initially, he ran it with the existing boss, American Teddy Mayer, but two such strong personalities were never going to last together. By mid-1981, Dennis was in full control.

What he accomplished, initially in partnership with designer John Barnard, has gone down in legend.

There was the first carbon-fibre chassis in 1981. Then there was the persuading of Ojjeh's TAG company to leave Williams, who had brought it into F1 as a sponsor, and join McLaren - then fund the development of a turbo engine from Porsche.

Dennis looks on as Ayrton Senna sits aboard the Honda McLaren during practice for the 1991 Belgian Grand Prix

After three drivers' and two constructors' titles between 1984 and 1986 with Niki Lauda and Alain Prost, McLaren's competitiveness began to slide, as they were overtaken by Williams-Honda. Dennis took on the brilliant Brabham designer Gordon Murray, persuaded Honda to leave Williams for McLaren and signed Ayrton Senna. In 1988, the McLaren-Honda-Senna-Prost combination swept all before them, winning all but one race.

McLaren dominated for three more years, even after Prost left at the end of 1989 following his famous fall-out with Senna. Then Williams, with Renault engines, became the dominant force of the early and mid-1990s.

But Dennis was not finished with his plundering of Williams. In 1996, he persuaded their star designer Adrian Newey to join him, a move that started the next period of McLaren domination in 1998-99, before Ferrari took over with Michael Schumacher.

Designer Adrian Newey brought titles for Mika Hakkinen in 1998 and 1999

Start of a downfall

The 2000s were up and down for McLaren. They were competitive in 2001, 2003 and 2005, but not in the even-numbered years. Then, at the end of 2005, while waiting to go out on the podium in Brazil with Renault's Fernando Alonso, who had just clinched his first world title, Dennis asked whether the Spaniard would like to drive for McLaren one day.

It turned out Alonso had been dreaming of nothing else since he was a young boy and he duly joined in 2007, alongside a novice called Lewis Hamilton.

Arguably, this was the beginning of the end for Dennis. He had promised Alonso priority status in the team but then reneged on it when it became apparent Hamilton - who Dennis had nurtured since he was 11 years old - was just as good.

Michael Schumacher hands Dennis the constructors winners' trophy in 2007

A series of rows followed, culminating in a cataclysmic weekend in Hungary. Hamilton double-crossed Alonso in qualifying by refusing to let him by as agreed during the 'fuel-burn' laps, effectively denying him a fair shot at pole position. Alonso retaliated by blocking Hamilton in the pit lane so he could not do a final lap. Dennis failed to control the fall-out.

Alonso threatened to go to the FIA, motorsport's governing body, with emails he had that were pertinent to the then-ongoing 'spy-gate' case, external if Dennis did not back him in the championship. He later apologised and withdrew the threat - but not before Dennis had phoned FIA president Max Mosley and 'fessed up'.

The result was a $100m fine for illegally possessing confidential Ferrari information and being thrown out of the constructors' championship.

Standing on the steps of the McLaren motorhome with Mosley in a photocall intended to project an image of 'no hard feelings', Mosley reputedly leaned over and whispered in Dennis' ear: "$10m is for what you did; $90m is for being a ****."

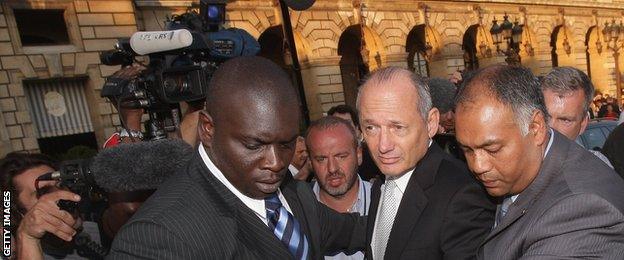

Dennis was summoned to the FIA headquarters in September 2007 over the 'spy-gate' case

That remark betrays the difficult relationship Dennis had with both Mosley and his ally Bernie Ecclestone, the F1 commercial boss, for much of his career.

Two years later, McLaren were again in trouble during the 'lie-gate' scandal, when Hamilton and team manager Dave Ryan were found to have lied to the stewards at the Australian Grand Prix. Ryan took the fall for that, publicly taking the blame and sacked.

Falling out with Ecclestone and Mosley, though, does not necessarily reflect entirely badly on Dennis, for neither man is everyone's cup of tea.

In fact, a matter of days before his ousting last November, Dennis' fellow team bosses were bemoaning some aspects of his impending fall, saying he always meant well, and had the best interests of F1 at heart.

An example of this was a meeting of team bosses in Abu Dhabi in 2015, when Ecclestone and his boss Donald MacKenzie were making it difficult for Renault to finalise their return to F1 as a team owner by arguing over financial terms.

Those present report how Dennis tore into them, insisting they "pay the ******* money", for the good of the sport. It did the trick.

Dennis' relationship with F1 boss Bernie Ecclestone has been a spiky one

A departure was on the cards

What happened last November had been on the cards for at least three years, possibly longer.

As long ago as early 2013, there had been claims of a fall-out at McLaren, of Ojjeh wanting Dennis out, of the chairman in turn wanting to take majority control of the company and trying to raise the money to do so.

Those stories would not go away. The deal that would have seen Dennis increase his shareholding from 25% by buying stock from Ojjeh (25%) and Bahrain's Mumtalakat investment fund (50%) never happened.

In early 2014, Dennis forced out team principal and chief executive Martin Whitmarsh, a close friend of Ojjeh, who was in a hospital bed recovering from a double lung transplant. Did that coup make things worse? Perhaps.

Certainly Ojjeh continued to make his life difficult. When, at the end of the season, Dennis wanted to keep Kevin Magnussen to partner Fernando Alonso in 2015, it was Ojjeh who stepped in and undermined him, forcing him to take Jenson Button instead.

It hardly helped that Dennis failed to secure a new title sponsor following the departure of Vodafone in 2013, which many blamed on his refusal to lower McLaren's rate card despite a changed commercial landscape and the team's drop in competitiveness.

Mansour Ojjeh - here with Lewis Hamilton at the 2015 Austrian GP - owns 25% of the McLaren Technology Group

The fateful meeting at which Ojjeh told Dennis his time was up appears to have been over lunch in mid-October at the McLaren factory.

Dennis was never going to go quietly and last autumn he took his own company to the High Court to try to prevent Ojjeh and the Bahrainis putting him on gardening leave. The case was thrown out.

That was Dennis' last throw of the dice. Insiders say he still had the option to go quietly with dignity, with a press release praising his contribution, saying he had decided to step down and hand over to a new generation, or words to that effect.

But, a fighter to the last, he rejected it. Perhaps he knew that no one would really believe he had voluntarily given up running the company in which he had invested his life's work.

So he went on his terms, throwing punches, with a statement saying he had been "required to relinquish his roles", warning of "consequences for the business", claiming the grounds for his dismissal were "entirely spurious".

Friday's McLaren statement finally buries the hatchet and affords Dennis the chance to depart with dignity and recognition, and few would begrudge him that.

For both McLaren and F1, life will not be the same without him.

Subscribe to the BBC Sport newsletter, external to get our pick of news, features and video sent to your inbox.

- Published30 June 2017

- Published15 November 2016

- Published11 November 2016

- Published21 October 2016