Ayrton Senna: Why, 25 years on, Brazilian's spirit & memory lives on as strong as ever

- Published

Remembering Senna - 25 years on

A year and eight days before the accident that cost him his life, on a warm and sunny spring morning, Ayrton Senna was surrounded by journalists in the paddock at Imola.

Five minutes or so after stepping out of his McLaren after first practice for the 1993 San Marino Grand Prix, the Brazilian was holding court, explaining his late arrival in Italy, just that morning, on an overnight flight from his home in Sao Paulo.

Senna, red overalls off his shoulders and tied around his waist, was encircled. The questions kept coming and, as time passed, one, young, wet-behind-the-ears journalist, attending his first grand prix in a professional capacity, was learning the hard way one of the perils of a media scrum.

Standing behind Senna, holding a dictaphone at full stretch over the driver's shoulder, the reporter's arm began to grow tired and ache.

What to do? Too hemmed in to swap arms, he couldn't remove it, or the interview would be lost. But the discomfort kept growing. Eventually, he made a decision. With trepidation, he rested his arm, as lightly as possible, on the shoulder of the biggest superstar Formula 1 had ever had - arguably ever has had.

Senna was not to know the journalist knew he shouldn't be doing it, felt terrible about it. He could have flinched, or moved, or objected to this invasion of his personal space. A number of current F1 drivers certainly would have.

But he didn't. He ignored it, as if it wasn't happening; stood yogi-still, tolerating the rudeness, apparently oblivious to it, until the questions were done, and then politely thanked everyone and headed off into the McLaren truck.

That journalist was this writer. And that morning Senna provided a glimpse into the kind, soft, gentle side of a man who, at other times, could be the personification of steel, ruthlessness, aggression and blind, unquenchable desire.

The dark and the light

Why was Senna talking to the media, unusually, after first practice? That demonstrates another side of him.

McLaren were using customer Ford engines, after partner Honda pulled out at the end of 1992. And Senna, frustrated at the lack of power compared to the Renault engine in the Williams, a car and engine he coveted, was said to be driving on a race-by-race deal.

He had already brilliantly won two of the first three races, but he knew Williams would eventually hit their stride, and his title hopes would fade unless something could be done about his engine.

The claim was that he had agreed to race at Imola only at the 11th hour, hence the late flight, and he used his interview in the scrum to rail against the injustice of it all.

The sub-text for that was how could he, Senna, be in this position?

What he really wanted was a Williams-Renault - in mid-1992 he had even offered to drive for them for free, but they had already signed Alain Prost, whose contract had a 'no Senna' clause in it.

In the absence of that, Senna wanted the factory Ford engine and was doing everything he could to try to get it - but that was by contract reserved for Benetton.

Senna was playing politics, using his status to apply pressure to try to improve his position. But within that, there was a sense of entitlement. The same mindset that, three years earlier, at the Japanese Grand Prix, had led him to deliberately ram his arch-rival Prost's Ferrari off the track at the first corner, at 160mph, because he was annoyed that organisers had refused to move his pole position to the cleaner side of the track.

Senna (left) pulls out from behind Alain Prost's Ferrari, seconds before they collided at the start of the 1990 Japanese Grand Prix

Two weeks after that, Senna gave the interview in which he produced what has become an iconic line: "We are competing to win and if you no longer go for a gap, you are no longer a racing driver."

That has been quoted many times over the years as an illustration of Senna's aggressively pure racing philosophy. But people forget that Senna was dissembling when he said it. Interviewer Jackie Stewart - a three-time champion, who could not be dismissed - was pushing him on the Prost incident, and Senna did not like it. The fact was, there was no gap - and Senna knew it.

A year later, he admitted he had rammed Prost deliberately, in retaliation for events at Suzuka a year before in 1989, when he was robbed of victory by motorsport boss Jean-Marie Balestre in dubious circumstances, following a collision with Prost, a decision that sealed the world title for the Frenchman.

This was the darker side of Senna - a man who would go to extremes, and sometimes display questionable morals, to get what he wanted, what he felt he deserved.

The allure of complexity

That was the thing about Senna. His appeal, the global fascination in him, lay not just in his staggering talent, but also in the depth and complexity of his personality. Yes, he was one of the greatest racing drivers the world has ever seen. Perhaps the greatest. But he was so much more than that.

He possessed a charisma so compelling it could silence a room. He could be magnetic to listen to. Immensely intelligent, he was a philosopher with a willingness to provide a window into the dangers of his profession, his own sense of mortality, and how that affected him.

"You are doing something that nobody else is able to do," he once said. "(But) the same moment that you are seen as the best, the fastest and somebody that cannot be touched, you are enormously fragile. Because in a split second, it's gone.

"These two extremes are feelings that you don't get every day. These are all things which contribute to - how can I say? - knowing yourself deeper and deeper. These are the things that keep me going."

No other racing driver has ever talked like that, about that subject, with such eloquence.

Death, too, plays its part in the iconography. When Senna was killed at Imola in 1994, his helmet pierced by a suspension arm as he smashed into the wall at the Tamburello corner, he was frozen in time at the age of 34. Age had added a few wrinkles around his dark eyes, but had not dimmed his movie-star looks. And his driving was as peerless as it had ever been.

The great drives

Ayrton Senna celebrates on the podium after winning the 1993 European Grand Prix at Donington Park, arguably his most complete performance

A little less than two weeks before that media scrum on that balmy morning in Emilia-Romagna in 1993, Senna had driven arguably his finest race.

This writer was there, too, this time spectating, standing in the freezing rain at Donington Park's chicane, waiting for the cars to come around on the first lap of the European Grand Prix.

As ever at a British F1 race in those days, the circuit commentary was almost inaudible. There was no internet or smart phones to carry instant news. I had no radio. But as the noise of the cars embarking on their first lap began, a buzz began to flow through the crowd. Something special was happening.

As the cars burst into view and rounded the chicane, Senna, who had started fourth, was already up to second, and, right up the back of the leading Williams of Prost, clearly about to be first.

Senna had just produced one of the greatest opening laps ever seen and, after doing so, proceeded to disappear off into the distance and make the rest look like they might as well not be bothering.

Senna did that a lot. There are too many great drives to mention them all. But he marked himself out as something truly special from very early on.

He should have won his sixth race, the 1984 Monaco Grand Prix. In a midfield Toleman, he was catching Prost's leading McLaren hand over fist in the pouring rain, and was right behind when the race was called off at half-distance.

The following year, his maiden win, in the 1985 Portuguese Grand Prix, came with one of the greatest wet-weather drives in history, finishing a minute ahead of Michele Alboreto's Ferrari, and at least a lap clear of everyone else.

That year, his Lotus was not the fastest car, but Senna took seven pole positions in 16 races.

He clinched his first title, having moved to McLaren in 1988, with another stunning drive, fighting back through the field at Suzuka in Japan after dropping to 14th following a poor start, catching and passing Prost, now his team-mate, in the drizzling rain.

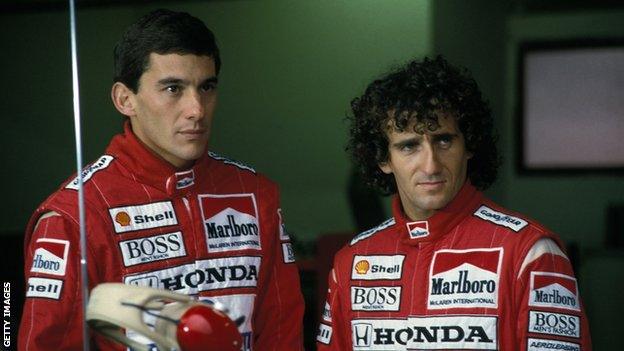

Senna and Prost pictured in 1988, the year they became McLaren team-mates. Their rivalry dominated F1 in the late 1980s and early '90s

And then there's Brazil 1991, when he held off Ricciardo Patrese's faster Williams on slick tyres in a late-race rain shower despite a car stuck in sixth gear.

By the end of that race, Senna was so exhausted he could not get out of the car unaided. On the podium, he could barely lift the trophy to acknowledge the adoring Brazilian fans, who revered him as a kind of demi-god.

To the limit - and beyond

This was a man who arguably dedicated himself to his sport more intensely, gave more of himself in the unbending pursuit of success, than anyone in history.

The transparency of how much it meant to him was another part of Senna's powerful appeal, but in the end it might have been his undoing.

It will probably never be known exactly why he went off at Imola on 1 May in 1994. His steering column broke in the crash. Did it break before it? His Williams team said no, and their technical bosses Patrick Head and Adrian Newey were eventually acquitted after a long, drawn-out legal process in Italy.

They always argued that the accident was caused by a combination of factors, by the diffuser stalling, robbing his car of downforce, as Senna went over bumps at the 190mph Tamburello corner, taking a tighter line than the lap before, on tyres that were low in pressure after a safety car, trying to stay ahead of the faster Benetton of Michael Schumacher. Damon Hill, his team-mate of the time, says he believes that, too, having seen all the data from his car.

Ayrton Senna sat in his Williams before the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix at Imola

Senna went to his death believing that Schumacher's car was illegal at the start of that year. It may have been - illegal software was found in it, although no proof was found that it was used. Either way, the Benetton was certainly faster. But somehow Senna had put the difficult, unpredictable Williams FW16 on pole position for the first three races of the year.

Head and Newey have always maintained that those poles were down to Senna, not the car. His average pace advantage over Hill in those qualifying sessions was a massive 0.922 seconds. In the first race of the season in Brazil, trying in vain to stay with Schumacher, Senna had lapped Hill by just after half distance.

Right to the end he was pushing the limits, forcing cars faster than anyone else could make them go, achieving things that should not have been possible, but that he somehow brought to light.

That's why, 25 years on, his spirit and memory lives on as strong as ever in the hearts and minds of everyone who knows anything about Formula 1. And always will.