Rachel Atherton: Living in extreme cycling's first family

- Published

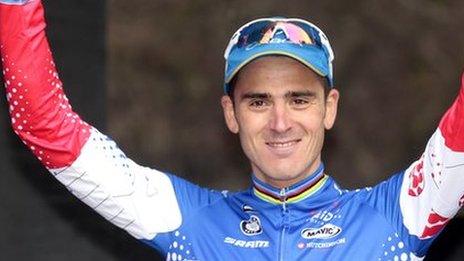

Rachel Atherton: Mountain bike world champion

Even the rolling, open hillside of Powys can be claustrophobic after a while.

That's how Rachel Atherton feels. The 27-year-old is starting to outgrow the beautiful, stone farmhouse complex she and her two brothers call home. She has all but outgrown her sport.

For the second time in her downhill mountain biking career, Atherton has finished the year as both the world champion and World Cup series winner.

When BBC Sport's cameras arrive, less than two days have passed since she wrapped up the latter title in Austria. Also here is 28-year-old brother Gee, who finished the men's World Cup season in an agonising second place, having led until the final race.

The two of them and older brother Dan, 33, form Atherton Racing,, external a leading professional mountain biking team. They live, work, and travel the world together.

At the end of a long season in one of the world's more dangerous sports, maybe it's a bit too much.

"It does get pretty intense," admits Rachel, standing in the courtyard outside the house she and Gee share, looking across to the cottage Dan inhabits.

"There are a lot of arguments between Gee and I, and Dan and Gee. But you've got to sacrifice something to have this life - and living with your brothers is a sacrifice."

Everything is here: the bike workshop with its three attendant mechanics, the small gym the three must share, the office with manager Dan Brown and assistant Gill, and occasionally a coach and Tom the bike washer.

Imagine an F1 team living together all year. Fernando Alonso in the cottage, Lewis Hamilton and Sebastian Vettel in the farmhouse. Then you'd see internal combustion. This is an F1 team in miniature, the same complex dynamics only heightened by the family bond.

How a local 10-year-old invaded the Athertons' private back-yard MTB course

Dan's solution is to seek therapy in digging.

Across the narrow lane outside the farmhouse you will find a large field given over to a series of enormous dirt mounds, sculpted into jumps and berms. This is the work of Dan Atherton the artist.

"He must have been in the digger at six o'clock this morning, because he woke me up," says Rachel. "I wasn't happy."

Dan pauses his digging. "Bright and early," he replies. "There's a lot to do, you know? You've been away for a while so you need fresh stuff to ride."

Formerly a downhill rider like Rachel and Gee, Dan has moved across to the newer 'enduro' discipline. Moreover, he has become something of a guiding presence. With his digger he not only shapes the outlandish jumps in the Athertons' back garden; he moulds his siblings' skills.

"He'll build something, and we'll ride it and have fun, but then he'll change it straight away," explains Rachel. "You're never riding the same stuff, which is probably one of the reasons why Gee and I are such good racers. Dan is always working."

It was Dan who, when the trio were growing up in Devon, started making small jumps on patches of scrubland. It was Dan who, when they moved to Powys, had the vision to begin carving out downhill runs. In large part thanks to him, the area is now a thriving hub of mountain biking.

Five miles down the road is the Revolution Bike Park,, external dominated by an old quarry recently handed new life as a daredevil biking resort.

Today we are lucky. The sun is out and the air is still - perfect conditions for a quarry descent.

Few things are this beautiful. Picked out in bright yellow team uniforms, against a magnificent skyline of Welsh peaks and the village of Llangynog, Dan and Gee plunge down the hillside before soaring from jump to jump.

You wonder how they avoid serious injury, and the obvious answer is they don't. Later, gathered around a computer watching old videos, Rachel prompts Dan about the time "his head nearly fell off".

Ride the Revolution Bike Park quarry in Powys with Dan and Gee Atherton

Dan recalls: "I was just riding some dirt jumps, like we do every week. I went over the bars and had a crash. I remember, at the time, thinking it wasn't that bad."

"And what did you actually do?" Demands Rachel.

"I broke my neck."

Gee chips in: "It was about as bad an injury as you could get without dying or being paralysed. You were lucky to survive it, weren't you? It was close."

Nobody here has emerged unscathed. Rachel's was less ordinary, colliding with a pickup truck while on a road ride in 2009, just after she first completed the double of the world title and the World Cup series. She wrote off the entire season.

Now, at last restored to the heights of downhill, she is staring at six months of training in the gym - when not at bike shows or testing new equipment - before it all begins again.

This is not an Olympic sport, despite years of vague machinations and mutterings about the inclusion of downhill. Nobody expects that to happen soon, and Rachel is no longer bothered. So what is there left to achieve?

"This has been an amazing year. It's been a long time in the making, after a lot of injuries in the past, and it's all come together," she says.

"But you can always win more. I didn't win every single World Cup, and that's something I've always wanted to do - every World Cup, every race. That's a big goal.

"I've only been world champ twice, and I've been racing for 15 years. It's that little edge you can find, always pushing yourself and trying to be faster."

For most people, winning every available race on the calendar would be enough. Atherton's ambition stretches further.

"Dare I say it, I'm not as fast as the boys yet. So maybe that will happen one day," she says.

"Growing up with brothers is the best thing for a young girl to do - chasing the brothers around on the bike. I started comparing my times with the guys and then I started to get hurt a lot, because maybe I was going too fast. I've backed off a bit but it's always there in the back of my mind.

"Qualifying in the top 80 men at a World Cup would be an amazing thing - I'm at about the 100 mark right now.

"We race the same bikes, on the same tracks, every weekend. Our times are getting closer and closer, all the girls are getting faster and stronger. It's going to happen at some point and I hope I'm the one to do it."

- Published2 September 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2016