Playing in the first Masters and teaching the Duke of Windsor

- Published

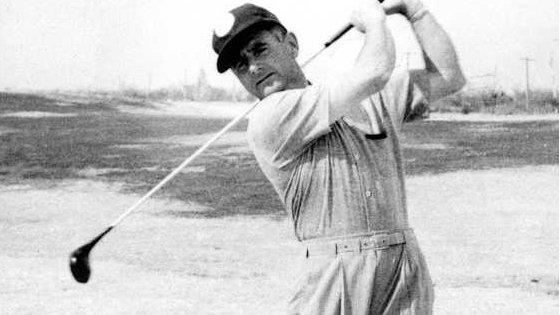

Samuel Henry 'Errie' Ball played in the inaugural Masters tournament with his friend Bobby Jones

Until his death in Florida on Wednesday at the grand old age of 103, Errie Ball, a transplanted Welshman who made good in America, had one hell of a claim to fame. He was the last survivor of the first Masters of 1934.

Errie never won a major championship and rarely featured at the elite end of the sport. He may not have lasted the pace that March week 80 years ago either but, boy, how he made up for it in a different way. Nobody in the history of the game lasted as long as Errie.

The winner of that inaugural event, termed the Augusta National Invitational Tournament, was Horton Smith, but Smith checked out in 1963. The runner-up was Craig Wood, and Wood went in 1968.

Of the top-10 at that first Masters, one player died in the 1940s, one in the 1950s, four passed away in the 1960s, one in the '70s, '80s and '90s with only Paul Runyan and Errie surviving into the new millennium. Runyan died in 2002 at the relatively spring-chicken age of 92.

He may have lacked the trophies and the profile of some of these men but his was a remarkable life all the same. Unique in so many ways.

Who was Errie Ball? | |

|---|---|

Qualified for the US Open 10 times, played in 12 PGA Championships, appeared in the Masters twice and in the 1936 Open Championship |

When we first spoke, Errie was 95 years young and had not long stopped shooting his age on the golf course. He spoke of Bangor, his birthplace in north Wales, and Lancaster, where he spent his early years as a budding professional under the watchful eye of his father, Harry, who was the pro at Lancaster Golf Club.

The game was in the blood right from the off. Not just from his father but earlier than that, from his great uncle, John, who in 1890 was the first amateur to win the Open and who won a remarkable eight British Amateur titles.

Born on 10 November, 1910, Errie set sail for America in 1930, arriving on the day Bobby Jones won the US Amateur at Merion, thereby sealing the storied Grand Slam. It was Jones who encouraged him to travel, explaining the possibilities for a young guy like him in the new world.

Errie reeled off some of the names in his unique life story. Harry Vardon, who was the same age as his own father and who he had watched as a young boy. Jones was a huge influence and something of a hero. Tommy Armour he remembered as a fine player with a caustic tongue.

The great Bobby Jones encouraged the young Errie Ball to make the move across the Atlantic

He recounted his time trying to teach Edward, Duke of Windsor, how to play the game, Mrs Simpson by his side the whole time. "It was at Oak Park in Chicago," said Errie. "And I gotta tell you, he wasn't much of a golfer."

His was not a glory-laden career. He qualified for 20 US Opens, played in 12 PGA championships and appeared in the Open on occasion. He was a jobbing pro and was successful at it.

His time was rich in ways other than major titles. Rich in friendships, for sure. He became head pro at Oak Park after the war and stayed for 24 years. He spent 24 winters at Tucson Country Club in Arizona. Willoughby Country Club in Florida was where he settled. This is a story of an everyman golfer who went on and on.

In 1957, he played in his second Masters, a gap of 23 years since his first. It was, remains and, most likely, will forever remain the longest span between competitions for any player at Augusta.

The epic sweep of Errie's life can be encapsulated in some of the people he spoke about, pretty much until his last days. Back in April, we communicated via email with the help of his friend, Gerry Knebels. "My ears have gone," said Errie. "I can't hear a damn thing. Other than that, I'm fair, for a guy of 103."

Errie was the last of his kind. The point of the email chat in April was the 80th anniversary of the first Masters at Augusta. Seventy two men had been hand-picked to play by Bobby Jones himself and 71 of them were dead long before Errie became a centurion.

"What do I remember of the tournament? I remember being honoured to get invited by Bob," he said. "And it was always Bob, not Bobby. He always thought Bobby sounded like a little kid's name so nobody called him Bobby in those days.

"I was doing all right until the par-three 3rd hole [now the 12th in the heart of Amen Corner]," he said. "The yips got me. I put the putter in front of the ball and then behind it and I got stuck. I couldn't stroke it! Eventually, I hit it and it was a disaster."

Ball came unstuck at this famous patch of the glorious course at Augusta National

Errie was 12ft away in one and 25ft away in two. He got so jumpy with the short stick that he almost putted straight into the greenside bunker. He may have been one of the first - and perhaps even the very first - to experience proper torment in the terrible beauty that is the most isolated patch of ground at Augusta National, but history tells us that he was far from the last.

He took six and his race was run. Down the generations, professional golfers have felt Errie's pain on that glorious short hole.

He remarked that if the long putter had been invented in 1934 that he might not have suffered so much on the greens - not that he would have used one, you understand. He wouldn't have dared. The thought of the ribbing he would have got from the likes of Armour would have put him off.

Beside him as he recounted a remarkable life was his wife, Maxie. He had met Maxie on the boat to America in 1936. They were both engaged to other people at the time but true love will have its way. They were married two months later. From that day, to the last day, they were together. A seventy-eight year odyssey.

He put his long life down to dear ol' Maxie - and a couple of shots of Scotch most nights before bedtime.

As news came through of his passing, American golf celebrated his life. There were stories of his indomitable spirit - he got his driver's licence renewed at the age of 100 - and his wit when still giving golf lessons at 101.

More than 80 years ago, America claimed him and it was there that he made his home and raised his family. It is quite right that the PGA of America, external were one of the first to salute him on his death, but they will not be the only ones.

In April, he signed off his email with another of the secrets of his long life. "I have good thoughts," he said, simply. Good thoughts and great memories of a life well-lived.

- Attribution

- Published3 July 2014

- Published28 September 2018