Ryder Cup: Fire still rages in steely USA captain Tom Watson

- Published

- comments

Watson has been an assured presence in dealing with the media

Tom Watson wants a happy ending, and it doesn't make much sense.

It makes sense that America want the Ryder Cup back, after seven defeats in the last nine contests. It makes sense that the PGA Tour would want him back in charge; after all, he was the last US captain to win on European soil, 21 years ago at the Belfry.

Where the logic breaks is that Watson wants to do it all over again.

This is a man who has won eight majors, who is 65 years old, whose life in golf is by even elite standards complete. Instead, 18 years older than his opposite number Paul McGinley, he is back in the bear-pit, back tearing afresh at the old itch.

This week at Gleneagles Watson has come across like a retired airline pilot or surgeon, all easy old-school charm and deep soothing voice, face and forearms leathery from long years in summer heat even as his hair stays preternaturally young.

To listen to him in his daily news conferences is to be reassured that all is right in the world. You could imagine him doing voiceovers for an insurance company or healthcare provider. All is calm, all is under control.

The urbane manner is no act. But neither is it the complete Watson. Underneath that benevolent exterior lies a man in whom the old fire still rages, who cannot step away even when all his contemporaries are feet up or far away.

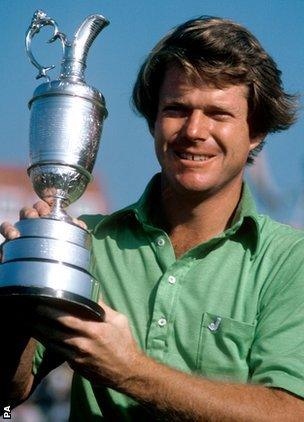

Watson won his second Open after beating Jack Nicklaus in their 'Duel in the Sun' in 1977

"Hating to lose," he has said, "is what taught me how to win. All those failures, chokes, early in my career - I despised that feeling so much, I didn't want to feel it anymore."

Most men mellow with age. Watson, who began his golfing life playing in cash games against his father and his friends in the bitter cold of Kansas winters, has been shaped by his six decades of victories and defeats but not fundamentally altered.

In his early years on tour he, like every other player, was overshadowed and overpowered by Jack Nicklaus. His response was to study the master obsessively, apeing his methodology, preparing for big occasions in the same exhaustive detail.

It worked. In time, pupil surpassed teacher. Watson beat Nicklaus into second place in a major four times, most famously in the Duel in the Sun at the 1977 Open, but never himself finished second to Nicklaus when it mattered most.

"Even though he is the nicest guy in the world, there is a hard steel edge to Tom Watson," confirms three-time Europe captain Bernard Gallacher, whose team were put away by Watson's resurgent USA at the Belfry in 1993.

Watson has said he knew the battle was won back then when he looked up with the late Payne Stewart on the decisive Sunday afternoon to see half-full grandstands and thousands of natives streaming for the exit. It will be his aim and exhortation again this week: empty the stands, boys, empty the stands.

Tom Watson led the USA to a 15-13 victory in the 1993 Ryder Cup at the Belfry

"We're not going to Gleneagles to have a nice time," he said this month. "We're going there to bring back the Ryder Cup.

"Win at all costs, basically. We're taking charge. I want players who hate losing as much as I do. No, more than I do. And I think I've got them."

Watson, like many Americans of his generation, thinks of himself as steered by a universal moral code. He believes there is a right way to play golf, and a right way for golfers to behave away from the course. This is a man who went to the crowd to defend Ian Woosnam in the frenetic finale to the 1991 Masters ("There's been a breakdown in decorum, and I don't feel good when partisanship spills over") and who resigned from his own club at their exclusion of some ethnic groups.

"My father lived by the belief that character is doing the right thing when no one is looking," he says.

Equally there is a darker side to his personality, a complexity that he prefers to hide behind the public charm and stirring deeds of the past.

For a man who has only Nicklaus, Tiger Woods, Gary Player, Walter Hagen and Ben Hogan ahead of him among the multiple major winners, he has endured brutal droughts in his game. After winning four Opens and 26 PGA Tour titles in six years from 1977, he then won just five events in the next 12 years, his putting stroke alternatively a wobble and a vice.

With struggles in his game came derailment in the real world. He drank a great deal - he has never formally described himself as an alcoholic, but he admits he hated the way it made him behave - and went through a divorce and subsequent estrangement from his children that he compared to death.

Watson watches on intently as Rickie Fowler (left) and Phil Mickelson practice at Gleneagles

Even now golf can trigger panic within him. He has dreams where he is putting for victory, the ball rolling all the way to the hole only to roll all the way back to his feet, or being so trapped by something unseen that he cannot swing his club.

"For nine solid years, I hated golf," he told Golf Digest recently. "(Former coach) Stan Thirsk said, 'You're really hating it now, aren't you?' 'I hate it, I hate it, I hate it.'"

Why, then, is he back at an age when his old rivals are content to contribute only as wise old sages in television studios, at an age when his critics here say he has relevance only as a historical figure to today's young bucks, and insufficient grasp of how the modern game works?

The lure of the Ryder Cup is one thing. In his four Cups as a player he never once finished on the losing side. He missed another only when his first child arrived before dawn on the previous day.

Then there is his deep bond with Scotland, where he won on his Open debut in 1975, where he won three more of his five Open titles. If this Ryder Cup had been back home in the States, he would never have taken charge.

Tom Watson's Open success in Scotland |

|---|

1975 Carnoustie - won 18-hole play-off v Jack Newton by one stroke |

1977 Turnberry - beat Jack Nicklaus by a stroke after 'Duel in the Sun' |

1980 Muirfield - won by four shots ahead of Lee Trevino |

1982 Royal Troon - beat Peter Oosterhuis & Nick Price by one shot |

2009 Turnberry - aged 59, runner-up after losing play-off to Stewart Cink |

"Just being in Scotland again is very special to me," he said this week.

"I remember as a boy reading the stories about the older players here from Allan Robertson , external[one of the first professional golfers] to Old Tom Morris,, external the big matches they used to have. They played 12, 15 rounds for one match. The game of golf evolved from that.

"There's a certain element in me that I feel like I'm part Scottish that way. I love the game so much, and I think the reason is the reading of the history when I was a young boy."

Maybe if the happy ending had come at Turnberry five years ago, that would have been enough.

Aged 59, he had stood on the 18th tee on the final afternoon of the Open needing only to par the last to win the game's greatest prize at an unprecedented age.

Instead he put his second shot, an easy eight-iron, through the green, missed the critical putt by six inches and fell apart in the play-off to cede victory to Stewart Cink by six shots., external "It tore my guts out," he admitted.

Watson (right) is consoled by Stewart Cink after losing a play-off for the Open at Turnberry in 2009

And so the itch remained. Watson has won more majors than Arnold Palmer. But it is Palmer and Player who make up the 'Big Three' with Nicklaus. Does the man who detests losing feel under-appreciated even by those who line up to fete him?

Maybe it is something else. Maybe, after a life defined by completion, Watson cannot live without it.

As captain at the Belfry, Watson searched long and hard for a speech to inspire his players. He settled for former US president Theodore Roosevelt's famous 'Man in the Arena' address , externalat the Sorbonne in 1910.

You'll know the one - the references to the man whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly only to come up short again and again.

It's both an obvious choice and an instructive one, particularly in its final line: "His place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat."

"I felt more pressure playing in the Ryder Cup than chasing a major," Watson said this week. "And I felt more pressure as a captain in 1993 than I did as a player.

"The pressure in the Ryder Cup, going to the first tee, it is something very electric, very intense.

"I love it. This is where I want to be."

- Published23 September 2014

- Published23 September 2014

- Published24 September 2014

.jpg)

- Published22 September 2014

- Published21 September 2014

- Published28 September 2014

- Published2 October 2016

- Published28 September 2018