Ryder Cup 2014: Little drama but plenty of romance at Gleneagles

- Published

- comments

There were still four matches on the course when Europe's win was confirmed

After the miracles and the 17th green shootouts, and all the gut-wobbling drama that is usually the staple of a Ryder Cup crescendo, it all ended uncharacteristically easily.

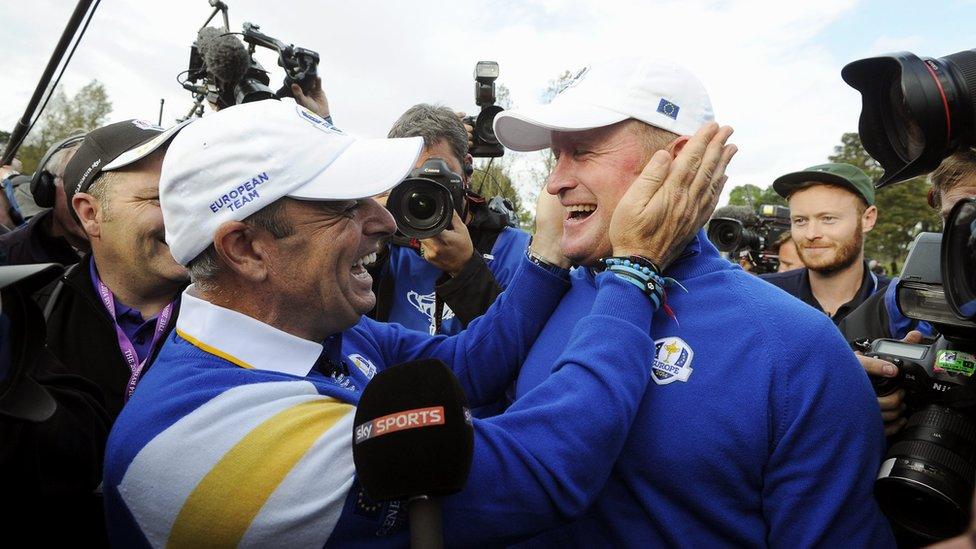

This was the Gimme In The Glen: Keegan Bradley conceding Jamie Donaldson's putt halfway down the 15th fairway to confirm the point that Europe needed, with almost half the matches still out on the course and almost half the course trying to get to that match.

The climax was not short of romance, though. To a list of unheralded names to have sealed the critical point in a Ryder Cup - Philip Walton, Jose Maria Canizares, Paul McGinley - we can now add Donaldson; 39 next month, on his competition debut, a player who had to wait until his 37th year for his first European Tour win.

Sometimes these showdown Sundays can feel like the best house party in the world. You're having a great time wherever you are, but the noise and cheers from just down the corridor always make you slightly anxious you're in the wrong room.

Donaldson earned the decisive point with a 4&3 win over Bradley

They can also make you feel short of breath and clenched of gut. What did those shouts indicate? Why the massed groans from beyond the trees?

Only early in the afternoon was that the case here, just before 1pm when the US were up in five of the seven matches in progress.

To come from 10-6 down overnight, the US needed everything to go for them and then a little bit more. That appeared to be happening when 21-year-old rookie Jordan Spieth was three up on Europe's lead-out man Graeme McDowell and Hunter Mahan led the home side's most successful player, Justin Rose, by four.

On the seventh, Spieth had a makeable putt to go four up himself. He missed, and with it the charge began to slow.

Ryder Cup final day in three minutes

McDowell gradually rediscovered his putting touch, birdied the 10th and then did likewise on each of the next three holes. Rose, two matches behind, went on a four-hole rampage of his own.

On the 13th, buried in a gorse bush, the Englishman ignored the pressure from behind to spear a long iron to within two feet. Mahan doffed his cap. A chip shot away, McDowell was rolling home a 15-foot putt on the 15th to go two up.

In between the two of them, Rory McIlroy was pulling the legs off Rickie Fowler on the 14th to win his own showdown 5&4. And, in those brief moments way out on the eastern fringes of the course, the battle was decided.

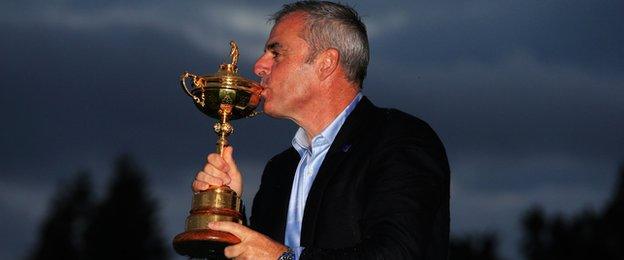

It was a campaign won with control and pre-planning. There had been fears coming into this week that captain McGinley, for all his enthusiasm and charm, would be outgunned by Tom Watson, an opposite number who has won eight majors and is loved in Scotland like no other golfer from other shores.

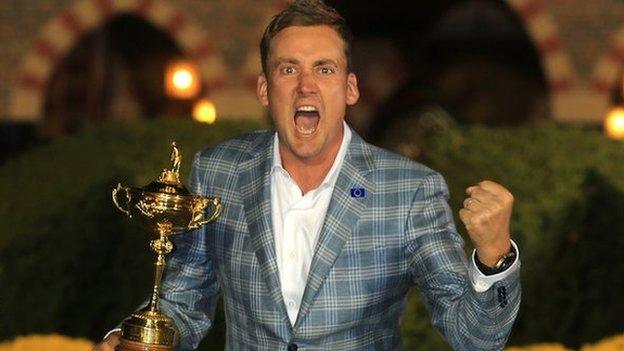

Neither were McGinley's three wildcard picks particularly successful. Ian Poulter could contribute only one point from three matches, Stephen Gallacher none from two, Lee Westwood two from four, although the leadership and nous the veteran brought were worth points on their own.

Singles scores | ||

|---|---|---|

Europe | Score | USA |

Graeme McDowell | Europe win 2&1 | Jordan Spieth |

Henrik Stenson | USA win 1UP | Patrick Reed |

Rory McIlroy | Europe win 5&4 | Rickie Fowler |

Justin Rose | A/S | Hunter Mahan |

Stephen Gallacher | USA win 3&1 | Phil Mickelson |

Martin Kaymer | Europe win 4&2 | Bubba Watson |

Thomas Bjorn | USA win 4&3 | Matt Kuchar |

Sergio Garcia | Europe win 1UP | Jim Furyk |

Ian Poulter | A/S | Webb Simpson |

Jamie Donaldson | Europe win 4&3 | Keegan Bradley |

Lee Westwood | USA win 3&2 | Jimmy Walker |

Victor Dubuisson | A/S | Zach Johnson |

16½ | Overall | 11½ |

6½ | Session | 5½ |

In everything else, though, McGinley was outstanding. For the past two years, he has been building relationships with each of his players - a dinner for two here, a daily phone call there, three nights spent at Victor Dubuisson's house when everyone else was claiming the French rookie was a closed book written in another language.

When the pressure came on, those bonds held the Europeans together. The captain understood his team and knew how they could mesh. In a sport that can be decided by the spin of a ball or grains of sand, he left as little to chance as a skipper ever has.

Ryder Cup 2014: The best shots of the final day

"He's re-written how captaincy is supposed to be," said veteran Thomas Bjorn, who has seen the Ryder Cup from both sides of the fence and was later ridden into the team press conference like a half-cut shire horse by a yee-hawing Donaldson.

"He's dealt with all the players in such an amazing way, and he's made everyone feel so special."

McGinley's key men responded. Rose led the way with four points from a possible five. McDowell, deliberately kept fresh for just three contests, won each of them. Dubuisson went unbeaten. McIlroy, there in every session, was the unbending spine.

For Watson, there was only weariness and recrimination. Barely had he issued a collective mea culpa - "They kicked our butts, and that's the bottom line" - than his star man Phil Mickelson became smiling assassin by spelling out in detail how preferable Paul Azinger's captaincy had been in 2008 at Valhalla.

McGinley has spent two years meeting, speaking and getting to know his players

At times, Watson - one of the most gifted golfers to have played the game, arguably the best there has been on a links course - has looked just what he is today: a 65-year-old man who understands how things were but not so much about how they are now.

Much has changed since he led the US to their last win on European soil 21 years ago - not only in terms of how much hoopla there is around the week but also in the quality of player he has at his disposal, and how those men behave, relax and think.

One of his vice-captains is 72 years old, another 63. The third is 47. That is less of a bridge between generations than a ladder.

The moment Europe retained the Ryder Cup

His most impressive men were the rookies: red-faced, fist-pumping Patrick Reed (three-and-a-half points), precocious Spieth (two-and-a-half), late-blooming Jimmy Walker (also two-and-a-half).

From his big names, he got very little. Bubba Watson lost every match he played. Rickie Fowler took one-and-a-half points from a possible five. Wildcard Bradley ended with one from three, and was left lamenting his captain's decision to bench his productive partnership with Mickelson for the whole of Saturday's play.

"The big excitement for me coming into Ryder Cup was playing with Phil," he admitted. "We talked about it months and months beforehand. We were bummed. It was a bummer."

The thousands of spectators cavorting around in the Gleneagles gloaming would beg to differ. What had begun with bedlam around the first tee and continued on the course in the afternoon - rivers of grinning faces and waving arms down either side of the fairways, great lakes of them around the greens - ended in a communal champagne-soaked love-in on the 18th fairway.

McIlroy appeared in every session and took three points

You almost felt sorry for Dubuisson, his the last match through long after the corks had popped, like a chap trying to bust his best dance-floor moves as the club closes, lights on, cleaners sweeping up around his feet.

It is becoming a familiar scene. In eight of the last 10 Ryder Cups, Europe have emerged triumphant. A competition once defined by how one-sided it was is now in danger of reverting to reverse type. By the end, only the Americans were complaining.

- Published28 September 2014

- Published28 September 2014

- Published28 September 2014

- Published28 September 2014

- Published28 September 2014

- Published25 September 2014

- Published28 September 2018