Olympics gymnastics: Why does bronze mean so much for Britain?

- Published

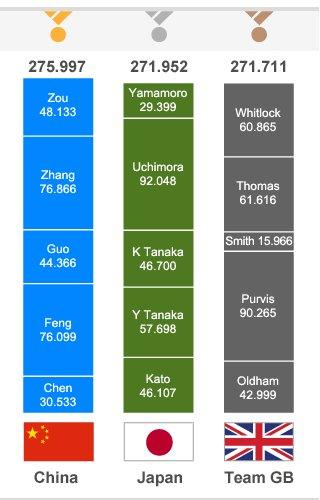

Lewis Smith scores well on the Pommel horse to put Britain into third position

Great Britain's men claimed their first gymnastics team medal at an Olympics in 100 years on Monday.

The team finished third behind China and Japan, despite having spent 10 minutes as the silver medallists before a successful appeal restored the Japanese to second place.

After the 2008 Games in Beijing, the British public is conditioned to expect gold medals in many sports, so why should bronze be celebrated here?

Why is bronze so important?

Britain has no history to speak of in men's gymnastics - certainly not the modern event.

The graphic above breaks down the team scores for the top three, showing the contributions of each gymnast. Note that Louis Smith, as a pommel horse specialist, contributed one exceptional routine to the GB total, while Japan's Kohei Uchimura provided a sizeable portion of his nation's score to earn silver.

When a British team reached the final in the 1924 Olympics, it still involved rope-climbing. Few sports at the Olympics have changed so vastly in that time.

Gymnastics has been dominated by a clique of nations - first, the Soviet Union and Romania, then China, the United States, Japan and Russia - for so long that breaking into that elite sphere requires money, talent, time and relentless effort.

This is not a sport in which gold medals can be manufactured overnight. Judges need to be convinced that nations are the real deal - and that can take years.

As gymnasts increasingly push the boundaries of human ability with their routines, breaking through requires ever-more talent and determination.

Winning an Olympic team medal proves that this crop of gymnasts has finally arrived at the sport's top table.

"There are people all over this arena who have been part of a 40-year legacy building up to this," said BBC gymnastics commentator Mitch Fenner.

"To think a British team is in contention with Japan and Russia. That cannot be put into perspective. Those are nations GB could not even look at a decade ago. Now they are fighting with them.

"Nine years ago, Britain's men were 23rd in the world. Now they are the Olympic bronze medallists."

How did Britain's rise begin?

Many in the sport would point to the influence of a man named John Atkinson.

A former coach, technical director and performance director, external for GB, Atkinson is considered the man who slowly put the building blocks in place for British success over several decades.

Olympic gymnastics: Bronze in team final is still unbelievable - GB men

"John Atkinson is British gymnastics. It was his vision to create this legacy," explained Craig Heap,, external a double Commonwealth champion for England in 1998 and 2002, now commentating for BBC Radio 5 live.

"He invented centralised training in this country. It had never been done before." He said: 'We'll put a roof over your head, feed you and maybe we can try to compete with the rest of the world.' We didn't have the money to do it properly then. Now, with funding, you can see what we've done."

The influence of Beth Tweddle cannot be discounted either. She ploughed a lone furrow at the top of the sport for years. In 2006, she won Britain's first-ever gymnastics world title just as Louis Smith was emerging from the British junior men's ranks.

She and coach Amanda Reddin were the first to establish the current generation of British gymnasts among the highest echelons of the sport, showing it was possible for British athletes to succeed in an environment previously dominated by the Eastern bloc.

This is not the first podium appearance for Smith. He won pommel horse bronze in Beijing. giving funding body UK Sport added reason to continue investing in the sport. Smith's charisma has also played its part in building the profile of gymnastics in Britain.

Where did the current team come from?

From a junior system put in place over many years and which is now considered unrivalled in Europe.

British gymnasts have been winning major titles at junior levels for almost a decade now. When Smith won Olympic pommel horse bronze in 2008, that success bled through to the world's biggest stage for the first time.

Mum 'so proud' of gymnast Whitlock

This is the next step and highlights a growing strength in depth as those successful juniors make the move to the senior stage - most notably Max Whitlock and Sam Oldham, who came through in the last 18 months to take the places of established senior gymnasts like Dan Keatings.

"You have to thank lottery funding," said Fenner. "A lot of money has gone in, but you have to produce results to guarantee that the money will keep coming in. The junior programme has needed money to support it and for its coaches to be encouraged.

"If a coach in a small club has a talented young gymnast on their hands, they need to be able to feel 'ownership' of that talent all the way through that gymnast's career. The key to Britain's success here at London 2012 is that every coach involved in the sport and with this team feels like a part of it. They have that ownership."

What effect has increased funding had?

The advent of National Lottery funding in the past decade has had a big impact on gymnastics.

Medals from the likes of Tweddle kept that stream of cash flowing, helping gymnastics clubs around the country put in place the facilities and coaching to produce the Olympic medallists we see today.

"The reason for this success is funding," said Heap. "When I went training full-time, I was still having to do work on my parents' farm. The other guys were doing jobs in the day then training at night. These guys now are funded to train three times a day.

"My coach used to work as a joiner, then come to the gym every night for a couple of hours, exhausted from working all day. Now our coaches are funded to prepare our gymnasts. If you were in school and said you wanted to be a coach, they'd have laughed your head off. Nowadays, coaches can make a career out of it."

One man who has done just that is Paul Hall, the coach to a number of GB gymnasts, including Smith.

Hall, who runs their base in Huntingdon, is the calmest man imaginable in a sport defined by moments of high drama. His controlled passion, vision and encouragement have been essential to British success, especially in the case of Smith, whose flamboyant personality is kept in check by his coach.

"Paul Hall is a man of great principle," said Fenner. "He is one of the architects, the first to break through with gymnasts in the pommel horse apparatus. Thanks in part to his work, the British team have gone from the worst pommel workers in the world to the best, as exemplified by Louis Smith. His is an immense coaching talent, but he is not the only one."

Should the medal have been silver?

Britain were temporarily awarded the silver medal when Japan's gymnasts performed poorly on the pommel horse at the conclusion of the team final. Should they have kept it?

The initial score for Japan placed them fourth, but they lodged a protest against the score of their final athlete to compete, Kohei Uchimura, who had struggled with his dismount.

The judges accepted the protest and added 0.7 to Uchimura's score, elevating Japan into second and pushing Britain down to third place.

Fenner says the judges made the right decision. "There were two issues for the judges to consider," he said. "Did Uchimura actually complete his dismount at the end of his routine? If he didn't, then the deduction would be 0.5 marks. However, if a judge said he didn't but later realised he actually did, then Uchimura gets those 0.5 marks back.

"How difficult was the dismount he was attempting? The judges gave him a 'C' grade for difficulty but he had actually done enough to earn a higher 'D' grade. That is worth an additional 0.2 marks. The judges took their time, looked at the video and saw the same replays we did. It was a brave decision, but correct and good for the sport."

- Published30 July 2012

- Published31 July 2012

- Published1 August 2012

- Published30 July 2012

- Published30 July 2012

- Published2 October 2013

- Published31 July 2012

- Published28 July 2012

- Published29 July 2012