Oscar Pistorius: Who was the man behind the brand?

- Published

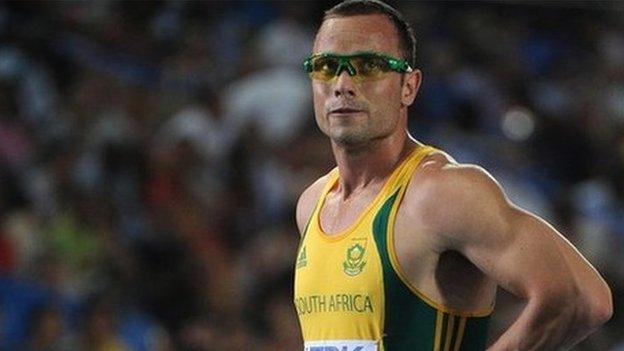

Oscar Pistorius: Profile of the six-time Paralympic champion

It was in Pretoria when I sat down in a cafe, looked up, and realised I was watching a dedicated 24-hour Oscar Pistorius Trial Channel on the television.

Only then did it dawn on me the extent to which South Africa was transfixed by a case that had left an indelible scar on the psyche of an entire nation.

Sport is no stranger to fallen idols; OJ Simpson, Hansie Cronje, Lance Armstrong the most obvious. But never perhaps quite like this before.

I had travelled to the capital to find out more about Pistorius' background and the wider significance of the trial that followed the shooting of his girlfriend Reeva Steenkamp.

Former training partner talks of his 'friend' Pistorius

Blade Runner. Trail-blazer. Icon. And now, killer. What lay behind what is arguably sport's most dramatic fall from grace?

The feats on the track that turned Pistorius into a household name, disability sport's first millionaire celebrity, and the symbol of hope that we could all relate to, are already familiar to many of us.

The six gold medals over three Paralympic Games, and his ground-breaking crossover into the Olympics, have helped take disability sport from the margins to the mainstream, turning him into the second most feted sportsman at London 2012, after Usain Bolt.

Less well known are the forces that shaped a complex character full of contradictions.

Pistorius may have been seen as a self-made hero, defying the amputation of both lower legs when still a baby, but his was a childhood of privilege too.

He was born into a wealthy Afrikaans Johannesburg family, albeit one traumatised by the death of his mother when he was just a teenager.

Pistorius became known as a man of faith, an inspirational role-model, and ultra-dedicated sportsman, but then there was the picture that emerged during his trial - a volatile, hot-tempered and aggressive enigma with an appetite for fast cars, beautiful women and guns.

So who is the real Oscar?

Pistorius won his first of six Paralympic gold medals at Athens in 2004

Average South African Schoolboy

Few people are as familiar with the origins of this most remarkable of sporting tales as David O'Sullivan, host of the Pistorius TV channel that I watched in Pretoria last month.

"I feel sad because we have so few role models in South Africa," he said when we met in an upmarket neighbourhood of Johannesburg.

"We have so few global icons, and he was one of them. He represented the country. But it all got stripped away in an instant."

A local sports journalist, O'Sullivan first met Pistorius in 2003, when the teenager's astonishing athletic ability emerged. The double amputee had taken up sprinting while at the prestigious Pretoria Boys' High School.

Media did not want to 'tarnish Pistorius'

In his very first competitive 100m race for the school, the 17 year-old remarkably smashed the Paralympic world-record over that distance.

"He had just recovered from a rugby injury, and had found to his amazement that he had broken the record without really trying," said O'Sullivan.

"He was just a pimply, shy little kid with braces on his teeth. If you looked at his prosthetic legs they were full of bumps and scratches. He was your average South African schoolboy."

Fast-tracked into the South African Paralympic squad, the next year Pistorius had won his first gold medal, in Athens. O'Sullivan closely followed the story of Pistorius' career, and even advised the young athlete on how to handle the increasing media interest.

"We established a relationship at that very early stage and he then asked me to assist him with writing a speech and on the strength of that I really got to know him.

"Physically, he grew. It was extraordinary how his confidence increased. He had so much self-belief."

Pistorius had been determined to lead a full and active childhood, despite having both legs amputated below the knee when he was just 11 months old as a result of a congenital defect.

As he himself told the BBC in 2012: "There wasn't much debate in my family. It was like 'you've got prosthetic legs, that's very nice, your brother's going to put on his shoes, you put on your legs, and off you go'. That was the mentality I grew up with."

Later, I visited Pretoria Boys' High School and watched as hundreds of pupils took part in running, rugby and hockey practice on beautifully maintained pitches as far as the eye could see.

Pistorius' name still features on the honours boards that hang inside, but such is the notoriety of their former student, no one from the school would agree to an interview, and access was denied.

The "blade runner" was the first amputee to compete in an Olympics at London 2012

Chasing a dream

But one man still very close to the athlete was willing to talk to us.

Zimbabwean Olympic 400m runner Talkmore Nyongani, Pistorius' long-term training partner had actually met up with the runner as the long trial wound to a close earlier that week, and agreed to give me an insight into his friend's motivation.

"He was chasing a dream, a big dream," he recalled when thinking back to their first meeting.

That dream was to make history by becoming the first amputee to run in an Olympic Games, and the able-bodied Nyongani was the ideal person to help prepare Pistorius for London 2012.

"I stayed with him for about five months in the same apartment, sharing the same food. He used to cook and I'd wash the dishes," said Nyongani.

'London 2012 changed everything'

"He was too determined. He just wanted to achieve. If he wanted an answer for something, he really wanted an answer. If the coach messed up somewhere, he would say 'no I want answers.' A lot of people just saw the friendly part."

The less friendly side of Pistorius' personality was slowly emerging.

Amid advances in prosthetics technology and mounting fears that his blades gave him an unfair advantage, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) had banned Pistorius from able-bodied competitions in 2008,, external a stance the athlete described as "crazy".

But after he contested the decision, the sport was then forced to allow him to take part in its events by a ruling from the Court of Arbitration for Sport.

In 2011, it was clear just how sensitive Pistorius had become about being excluded, walking out of a BBC Radio 4 interview after he was asked if the athletics authorities saw him as an "inconvenient embarrassment".

"When you get a difficult question there are ways to answer it and you don't need to get aggressive," respected South African sports journalist Graeme Joffe told me.

Joffe had become a business partner of Pistorius, co-owning a racehorse with him.

"I felt he was getting bigger than the sport and no one can be bigger than the sport," he said.

"Never before had South Africa been seen in such a positive light, but now it has all backfired," says sports journalist Graeme Joffe

Joffe reminded me of an often-forgotten fact - that Pistorius narrowly failed to qualify for a place in the individual 400m competition at the London Olympics, but was then conveniently named in the South African relay team anyway.

"Pressure from sponsors and politics made sure he was selected. It made a mockery of the selection criteria," insists Joffe.

"Oscar was the poster-boy of the Olympics, and everyone was getting their pound of flesh. But was he prepared for the new status? Never before had South Africa been seen in such a positive light, but now it has all backfired."

Sour grapes

Had the fame and fortune that came with the big-money sponsorship contracts gone to Pistorius' head? After he failed to claim victory in the 200m final at the London Paralympics, he accused Brazilian winner Alan Oliveira of effectively cheating.

"He was an idol to me, then suddenly we saw another side to him," Oliveira told the BBC last month at an athletics meeting in Sao Paulo.

"He said there was something wrong with my blades. He saw me at the Olympic village and refused to talk to me. He told the media that he apologised to me but that never happened. He apologised to the media but never to me."

"Oscar's outburst smacked of sour grapes," adds Joffe. "The majority of the South African media spun it to look like he was the victim. Oscar was made into an untouchable. No one wanted to dig a little deeper. For me he really acted like a spoilt brat."

Pistorius's back tattoo is a verse from the Bible: |

|---|

"I do not run like a man running aimlessly. I do not fight like a man beating the air. I execute each strike with intent. I beat my body and make it my slave." |

Corinthians 9:26-27 |

O'Sullivan recalls another incident in London where he claims he was told by Pistorius' room-mate, fellow runner Arnu Fourie, that he had to move out of the room he was sharing with his colleague because he had been screaming with anger at people down the telephone.

"He had to move out because Oscar had gone hysterical on the phone and was shouting and screaming. It transpires it was at his then girlfriend and a man who'd taken this girl on an overseas trip.

"I had the story confirmed by so many other athletes who said it was terrible to witness, this incredible meltdown."

Fourie later released a statement insisting he had left the room on medical advice ahead of an important race, but by now, there was little doubt Pistorius had begun to change, his private life becoming more and more turbulent.

In 2011 he allegedly fired a gun through the sunroof of a car, an incident which he has now been found not guilty of, and in 2013 he accidentally fired a gun in a crowded Johannesburg restaurant called Tasha's.

I approached two of the three friends that had sat with him at the table during that shooting incident last year, boxer Kevin Lerena and recently-crowned European champion British 400m runner Martyn Rooney, but both politely declined to speak to the BBC about what had happened that day, or about Oscar at all.

"He really seemed a different person to the public persona he was presenting," says author Mandy Wiener

Volatile and aggressive

"Over the years as the fame and money and stardom began to roll in, there were incidents," said Mandy Wiener, author of the book "Behind the Door" which chronicles the murder trial.

"He really seemed a different person to the public persona he was presenting. There were more and more of these incidents that were happening which showed Oscar to be more volatile, more aggressive."

"The media didn't want to scratch away at what was such a good thing for the country. Sportsmen are so popular in South Africa, because we get to go away from the corruption, crime and negativity."

But it was not just the media that seemed to give Pistorius special treatment. Pretoria security consultant Mike Bolhuis told me the police were guilty of the same thing.

"When he was involved in gun incidents, if he had been properly prosecuted at that stage then Reeva would be alive today," he said.

"South African law states if someone makes a mistake or if a gun goes off it must be properly investigated. It is a serious offence. His guns would have all been confiscated. And I think that would have had the necessary effect on him, thinking 'I need to be more careful.'

"I think the reason why those incidences weren't treated as the normal person in the public would have been treated is because he was Oscar Pistorius and that is a big problem in our country.

"Unfortunately celebrities will be treated differently because we want to help them, but we literally help them on the way down."

Pistorius was a role model that united white and black South Africans

Resilient nation

Others however, would still prefer to see the good in Pistorius.

"Oscar is a gentleman, he's somebody who sticks to his words," said Nyongani.

"In Europe he would tell me 'you are not fine Talkmore. Call your wife, there's my phone'. He's somebody who was so kind. I pray for him a lot."

At the University of Pretoria's High Performance Centre, the next generation of South African athletes benefit from the same world-class facilities and coaching that Pistorius did.

Money raised by international teams renting the centre helps to fund a sponsorship programme that aids aspiring athletes from poorer communities.

"What he did as an athlete is still inspiring and no one can take that away from him," insisted Katlego Sotsaka, a young black rower.

Andrew Harding reports on the background to the verdict

"He is still an inspiration for me even with the circumstances," agreed Dieter Rosslee, a white 19-year-old para-rower who lost a leg in a dreadful lawn-mower accident when a boy.

"When I lost my leg I saw him doing so well without two legs and he was a role-model of mine."

Toby Sutcliffe, the HPC's chief executive, believes South African sport can move on, despite the demise of a man who had, until recently, been the source of such pride.

"South Africa is a very resilient nation. The Oscar thing is a blip on the radar. The talent is there, the will to win," he said.

"South Africans have a winning nature. We will overcome it and it will be in the news and it will be gone again."

Before leaving South Africa I met up with the most successful South African Paralympian of all time, Natalie du Toit.

Like so many of her compatriots, the legendary retired swimmer, with 13 Paralympic gold medals to her name, is reluctant to talk about Pistorius, but what she does say is thoughtful.

"It is extremely sad what's happened," she told me on the terrace of a Johannesburg hotel.

"As a youngster it's important to remember that people aren't on a cloud. People do break down.

"Instead of putting people on a pedestal, this has broken down the barrier in which people think you live on a cloud just because you have achieved success."

South Africa would do well, perhaps, to heed Du Toit's words.

- Published12 September 2014

- Published12 September 2014

- Attribution

- Published12 September 2014

- Attribution

- Published11 September 2014

- Attribution

- Published10 September 2014

- Attribution

- Published3 December 2015