Oscar Pistorius: How Para-sport will recover from athlete's absence

- Published

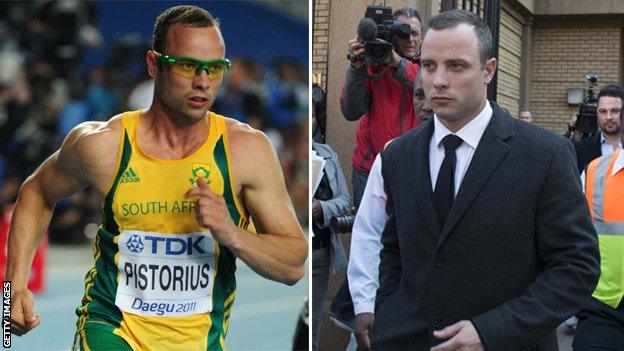

About 4.5 million viewers in Britain watched Oscar Pistorius in the T44 200m final at the London Paralympics

The trial of Oscar Pistorius began as the tale of a Paralympic and Olympic hero caught up in personal tragedy. By the end its connection to sport had ceased to matter.

This was still about the disintegration of an international icon. It was even more about the violent death of a young woman and the grief of her family.

Pistorius gave the Paralympic movement several unforgettable narratives: the sport-obsessed kid who refused to give up, the blade-runner who meshed flesh and technology, the champion who won multiple gold medals with thrilling late bursts, the disabled man who ran against - and beat - the able-bodied.

Pistorius's early life |

|---|

Pistorius had his lower legs amputated at the age of 11 months, having been born without a fibula in either leg |

By the age of two, Pistorius had his first pair of prosthetic legs and within days he had mastered them |

He played waterpolo and rugby in secondary school. He also played cricket, tennis, took part in triathlons and Olympic club wrestling and was an enthusiastic boxer |

In June 2003, he shattered his knee playing rugby and on the advice of doctors took up track running to aid his rehabilitation |

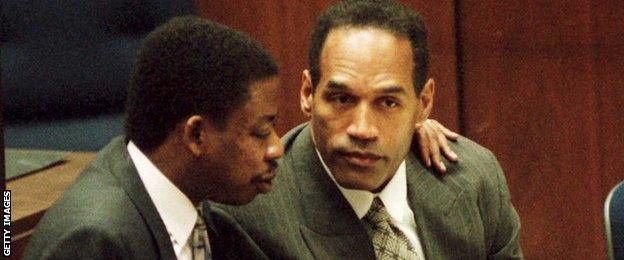

It made him both widely revered and richly fascinating. It also ensured that his public evisceration over the last 20 months would draw the world's attention like nothing since OJ Simpson's trial almost two decades before.

But just as Simpson's career as an outstanding running back for the Buffalo Bills and San Francisco 49ers did not mean that case (or his subsequent civil trial, nor imprisonment for armed robbery and kidnapping) somehow pertained to the NFL, so Pistorius's trial became increasingly divorced from his achievements on the track.

Long before Thursday's verdict, this was a human tragedy rather than a sporting one.

Like the OJ Simpson trial before him, the Pistorius case has gone beyond the parameters of sport

For many years Para-sport and Pistorius existed in a super-charged, symbiotic relationship. The sport had produced heroes before. Stories of courage and brutal training were to be found in every race, yet Pistorius changed his sport, and his successes changed his life.

About 4.5 million viewers in Britain alone tuned in to watch his T44 200m final at the London Paralympics in 2012, the biggest audience Channel 4 had attracted on a Sunday for seven years. A few days later 6.3 million turned in to watch his 100m showdown against Jonnie Peacock.

While there were other factors at play that summer, not least the draw of Britain's young tyro Peacock and the afterglow of the most successful Olympics in the nation's history, his allure was barely diluted elsewhere.

No other Para-athlete twice made the Time 100, the magazine's annual list of the world's most influential people. None of Pistorius's rivals could match his sponsorship deals with Nike, BT, Oakley and Thierry Mugler.

In Pistorius's absence, Alan Oliveira won gold and Jonny Peacock set a new British record at the Paralympic Anniversary Games in 2013

In those moments of hegemony, however, the sport was starting to move on. Peacock's victory in the 100m anointed him as the new darling of the British crowd. Alan Oliveira's astonishing late acceleration to beat Pistorius in the T44 200m created another new star.

Oliveira is six years younger than Pistorius. His physical attributes indicate that he may far surpass his South African trail-blazer's times. With the next Paralympics in his home country of Brazil, there would have been a new poster boy regardless of the events in Pretoria in February 2013.

"When I was coming through, Oscar was there for me and gave me words of advice and encouragement," Peacock told BBC Sport.

Pistorius competed at the able-bodied World Championships in Daegu in 2011

"Just before the 100m final in London he asked if he could pray for me. He was a nice person to be there, and in terms of what he did for Para-sport he made that first breakthrough.

"But London gave people more heroes. The sport is in such a better place now, and the Paralympics is bigger than one man."

Watching Pistorius first hand at the 2011 athletics World Championships, when his selection for South Africa's able-bodied team dominated talk in Daegu, South Korea, he was not only a pioneer but a solo missionary.

It was easy to forget that he was not actually the first Paralympic athlete to compete in world-class able-bodied events. His compatriot Natalie du Toit swam the open-water 10k at the 2008 Olympics, while USA's Marla Runyan, who is legally blind, finished 10th in the 1,500m at the 1999 Worlds in Seville.

Ireland's Jason Smyth, the double Paralympic champion who is also visually impaired, lined up in the 100m heats in Daegu before Pistorius's 400m competition had even begun.

Pistorius's "upside-down question-marks" powered him to T44 400m gold at the London Paralympics in 2012

But amputee Du Toit competed without a prosthetic limb, Runyan and Smyth without guides. It was Pistorius's blades and what they might achieve that both fired the wider public's imagination and took athletics into unexplored ethical areas.

Those distinctive "upside-down question-marks", as he described them, were the punctuation in a debate where scientific logic could play second best to the power of public image.

So universally admired was Pistorius, South African sports scientist Ross Tucker told the BBC, that biomechanical studies indicating the carbon-fibre blades conferred a significant advantage were less influential than the allure of his remarkable fable.

"There is such an impenetrable wall of PR support for Pistorius now that for a federation to take him on and say, no, you're not allowed to run, would be a PR disaster," said Tucker at the time.

Pistorius becomes the first amputee sprinter to compete at the Olympics

All that has changed. So too has the Paralympic movement, stronger since London, no longer dependent on a single talent, no matter how revolutionary.

"We must never forget the contribution that Oscar made - it was mind boggling," International Paralympic Committee president Sir Philip Craven told BBC Sport earlier this year. "But things have moved on.

"With Oscar, you are looking at a great athlete, someone who was passionate about athletics and really loved what he was doing.

"Prior to London 2012, Oscar was the superstar of the Paralympic movement. Interviewers said to me he was the only star. I said it would change in London, and it did.

"He was still a great star, but in London we saw so many other people coming through in the sport - people like Dutch amputee sprinter Marlou van Rhijn, American wheelchair racer Tatyana McFadden and Britain's Peacock and David Weir."

American wheelchair racer Tatyana McFadden, Dutch amputee Marlou van Rhijn, and Britain's David Weir are all stars of the Paralympic movement

Para-sport's future was not dependent on the verdict read out in the Pretoria courtroom, any more than heavyweight boxing was destroyed by Mike Tyson's conviction for rape or football by Dutch superstar Patrick Kluivert's sentence for causing death by dangerous driving.

"Oscar was just one athlete and there are a lot of great athletes in what is a massive organisation," Weir, who won four golds in London, told BBC Sport. "The Paralympic movement can live without Oscar."

- Attribution

- Published12 September 2014

- Attribution

- Published12 September 2014

- Published12 September 2014

- Published19 February 2013

- Attribution

- Published3 December 2015