Rio 2016: Brazil's first gold from the City of God favela

- Published

Rafaela Silva earns Brazil's first gold in Rio

"The place for a monkey is in a cage. You are not an Olympian." That was one of the text messages gold medallist Rafaela Silva received four years ago after being disqualified in the early stages of the London 2012 Olympics for an irregular manoeuvre.

Then she considered giving up judo. "The messages said I was an embarrassment to my family, so they really hurt."

But four years later, Silva came back to bring Brazil its first gold medal of the Rio games in the 57kg judo division.

Silva's victory on Monday was hard-fought. She faced inequality, poverty and racism growing up in one of Rio's toughest neighbourhoods, the City of God.

Her family enrolled her in free judo classes when she was a child to keep her away from gang life and drugs.

"This means so much," said Adriele, a favela resident and budding judo star.

"We are very proud, because it's someone who came from the same situation as as we did, and there she is, and so then you think, wow, I can get there, too"

In an interview with the New York Times, external, Silva's coach, Geraldo Bernardes, said that he saw potential early on:

"Rafaela was always really aggressive, but in a way that I could direct her in a way that was good for the sport.

"Judo requires from the athlete a lot of sacrifice. But in a poor community, they are used to sacrifice. They see a lot of violence; they may not have food.

"I could see when she was very young that she was aggressive. And because of where she is from, she wanted something better."

Silva after her win

Cidade de Deus

Silva's story exposes the deep racial tension in Brazil as well as the difficulties of life in the favelas.

According to Alexander Wolff, external, from Sports Illustrated, Rafaela "spent the first eight years of her life in the City of God, getting into fights with boys and getting expelled from school".

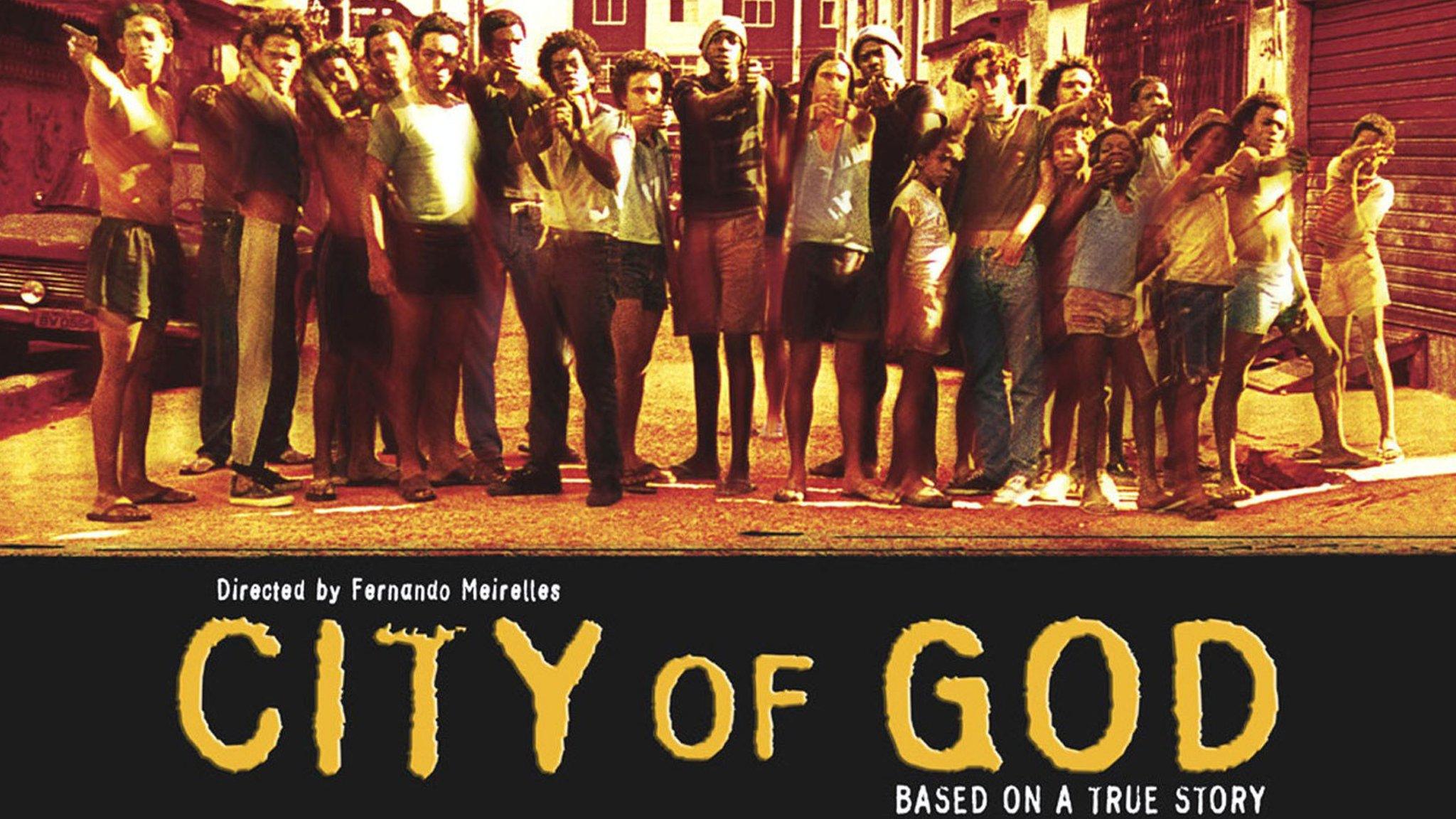

The notorious Cidade de Deus, or City of God, is Rio's famously violent favela. It acquired its notoriety after a 2002 film which chronicled its decline into drug battles, criminal rivalries and excessive violence between the 1960s and 1980s.

Wolff, who profiled Rafaela, wrote: "The movie's tagline - 'If you run, the beast catches you; if you stay, the beast eats you' - captures the fatalism of life in the cramped shanty towns where one of every five Cariocas (native of Rio de Janeiro) lives, often trying to avoid crossfire between drug gangs and police."

Little seems to have changed.

Juliana Barbassa, a native Brazilian and author of "Dancing with the Devil in the City of God", told the BBC the City of God was formed in the 1970s when the government resettled different communities on the outskirts of Rio. Without access to adequate infrastructure or jobs, the neighbourhood fell under the control of drug-trafficking gangs

"It's a situation of literal marginalisation- they were pushed to the margins. To get out if it as Silva has done is really challenging. She literally had to fight her way out of the environment."

Silva beat Sumiya Dorjsuren of Mongolia on Monday

Ms Barbassa explains that prior to the 2014 football World Cup in Brazil, the government tried to invest in the favelas and bring them back under government control. They put police forces into the neighbourhoods and promised to bring in social services. But the state failed to bring in the services and the programme struggled under the country's financial crisis.

As a result, violence is coming back into these communities. RioOnWatch, external, a community reporting project, says many current residents of the City of God are "living in a state of fear" as a result of frequent gunfire, continual police operations and the presence of armoured tanks.

They say residents feel their rights have been violated. Some see the continual police operations as a "form of discrimination".

Speaking to RioOnWatch, 20-year-old Mauro Leocadio, said: "The other day I was leaving the house and going to my course when I saw a squad of shock troop vehicles. This doesn't happen in affluent areas. I wonder why it is necessary to have so many armed men like that. I felt vulnerable.

"The UPP (Pacifying Police Unit) is not a project of peace, it is far from that. Their presence has not ended the violence."

Subtle racism

For many, the Olympics haven't helped to ease feelings of inequality either.

Ms Barbassa said: "The city that we got as a result [of Olympic development] is a less equal city, a city in which much of the investment was diverted to the wealthier areas and a city that doesn't serve the majority of its populations like it could have.

"In Brazil, socio-economic inequality dovetails with racial inequality. You can see that when you go from the elite gated communities that are mostly white - almost everyone is white except the cleaners or the guards. In the favelas people are mostly Afro-Brazilian or mixed.

"Brazil basically hasn't had a serious confrontation with its race issues."

Marta Arretche, a political scientist who studies inequality at the University of Sao Paulo, agrees. She told the Associated Press. "Behind the apparent peaceful melting pot there's a lot of tension and not much open talk about race."

Rafaela's win

Rafaela and her older sister Raquel are both judo champions who trained under Bernardes but Raquel did not qualify for the Olympics.

Through tough times the girls have stuck with judo and their coach.

Surrounded by family and her fans after her win

Raquel told the New York Times, external it was hard for her sister to start up again as a result of the racism she experienced after the London Games.

"Rafaela got depressed. She watched television all day and cried alone in front of the TV. Our mother cooked her favourite things to cheer her up, but that didn't work."

In the end, Bernardes encouraged her to start training again and Rafaela's tenacity prevailed.

On Monday, after beating Sumiya Dorjsuren of Mongolia, she ran, filled with emotion, to hug her family and coach - a win she celebrated just a few miles from the favela.

Watching on as she won were Brazilian children training at the Instituto Reaceo where Silva practices.

"I think she is a big inspiration because she lived there [in the City of God] and that didn't keep her from training," said 11-year-old Matheus.

"She had no money for the bus so she'd walk all the way here to practice, to follow her dream of getting that Olympic medal."

The girl once ostracised for her race is now being celebrated across Brazil. "They said I was a disgrace," said Rafaela. "Here I am: an Olympic champion in my home town."

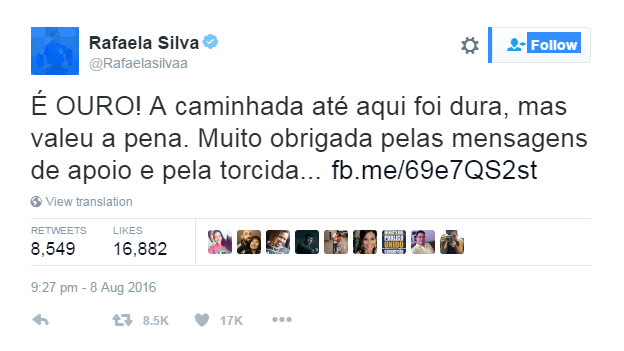

"IT'S GOLD! The road here has been tough but it was worth it. Very grateful for all the messages of support and to the fans"

Fans react to Silva's win

- Published9 August 2016

- Attribution

- Published6 August 2013