Fukushima: How baseball and Tokyo 2020 are helping the region recover from 2011 disaster

- Published

- comments

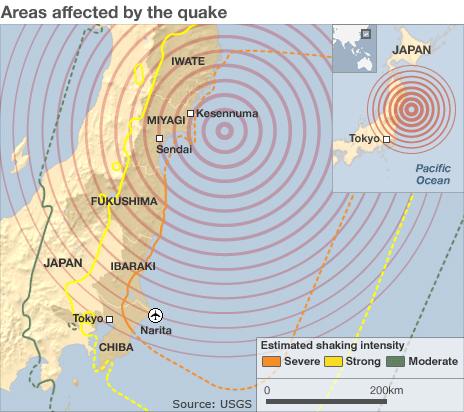

The quake hit at 14:46 local time (05:46 GMT) and this is how the disaster unfolded

Mr Kumagami sits cross-legged on his tatami floor flipping through reams of photos.

There's a picture of a silver car, a family gathering, a snow-dusted garden.

Then there are windows covered with blue tarpaulins, a buckled wooden floor, a hallway with the ceiling caved in, piles of stuffed bin bags.

"This is my home," he says pointing. "But I can never go back there. The army turned up wearing protective masks and told us all to leave."

The photos are all Mr Kumagami has to remind him of where he lived for 40 years. He is one of nearly 165,000 people who were forced to evacuate in March 2011 when the Great East Japan Earthquake struck.

At magnitude 9.0 it was the most powerful quake ever experienced by a country well used to earthquakes. An hour after the first tremor, tsunami waves hit all along 670km of Japan's north-east Pacific coastline. Up to 18,000 people were killed.

The tsunami is also responsible for the resulting catastrophic event at the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Okuma town on the Fukushima coast.

At a height of around 15m, the rolling wall of seawater breached the plant's protective defences and disabled the generator for the reactor's cooling system.

The reactor went into meltdown. The accident was deemed on a par with Chernobyl, albeit releasing less radioactive material.

Nevertheless, radiation did spread in the wind, and Mr Kumagami's hometown of Namie lay just 10km to the north-east of the reactor.

Mr Kumagami cannot return to his damaged former home

The whole town and several others around it were evacuated as a 20km exclusion zone was established.

"I didn't know how much radiation was in my body. I had no food or any idea what to do. I had to sleep in my car. I was in a state of panic," he says.

There's one other photo in Mr Kumagami's new apartment - his ninth residence since 2011. It's bigger than the others and sits proudly in his living room next to his TV.

"That's my grandaughter," he explains. "In the eight years I've lived here she's never come to visit me.

"My daughter and her husband won't let her. They live in Tokyo and they're afraid of the radiation. It makes me sad."

Kiyo is a joker, a self-styled "Japanese Mr Bean", and he does the facial gymnastics to match.

Spotting me walking by, his eyes almost pop out of his head. A smile with more mischief than teeth stretches across his face. In a crowd of over 400 locals, the one red-haired white man sticks out. I am that sore thumb - and the other four fingers too.

Kiyo can't pass up this chance. He simply has to perform his English to entertain his friends.

"Oh! Hello! Your name? You are from?"

The old self-deprecating broken English gag is always an audience favourite.

It's a bit of fun, a comedy interlude to another Sunday afternoon at the ball game. In any case, their team isn't doing too well at bat today, and they don't see many foreigners round these parts. Not anymore, anyway.

"Why you are here?" he asks. It's a fair question.

When you think of must-see sporting events in Japan, the Route Inn Baseball Challenge League won't feature high on many lists. This is a minor league game in Koriyama's municipal stadium. This is pretty far-removed from The Big Show.

When I explain that I'm interested in baseball and the Olympics and what all that means to Fukushima and its people who've been affected by disaster, the joker's mask slips, his face still with sincerity.

"Thank you for coming to Japan," Kiyo says to me, and he shakes my hand.

It may have been eight years ago now but the disaster's effects are still being felt in the region. Fukushima's reputation is still fused with its nuclear accident and the local economy is battling to recover. Sport has tried to serve as a vehicle to restore pride back to the region and help change its image. That's where baseball comes in.

Kiyo is a fan of the Fukushima Red Hopes, a minor league team making a major contribution to their community.

He has a busy job as a chef in a Tokyo hospital but comes home when he can to cheer on his team. Rugby may be Japan's latest fancy, but baseball is its first love.

The Red Hopes are managed by Akinori Iwamura, a former player in the American Major League who took charge in the aftermath of the 2011 disaster.

The 40-year-old had no prior link to this part of Japan, which lies over 250km from Tokyo and feels like a world away, surrounded by a green landscape of rice fields, hills and rivers.

"I was coming to the end of my playing career and I could see the people of Fukushima trying to get on with their lives in the face of adversity following the disaster," he says.

"I asked myself if there was anything I could do to help. So I thought about using the power of baseball and heard there was an opportunity at this team. We want people to come and watch a game and forget about their stress; we want to bring a smile back to their faces."

It's been five years since Iwamura began his mission. And judging by the animated faces in attendance at the Red Hopes game, the team is having some form of positive impact.

"No one used to laugh like this," says Yoshitsugu, a 49-year-old mechanic who is a Red Hopes regular.

"After 2011 everyone was down; we couldn't watch TV without being reminded about what happened. This team makes us feel good."

The crowd at a Fukushima Red Hopes match in Koriyama

Like around 40,000 of Fukushima's citizens, the Red Hopes themselves are currently displaced.

Their regular home is at the Azuma Stadium in Fukushima City, 60km north of Koriyama. For now, the sound of drums and co-ordinated chanting echoing around the bleachers has been replaced by the chugging of diesel engines.

Azuma Stadium is undergoing a transformation in order to be ready to welcome the world to Fukushima next year when Olympics comes to town. The Tokyo 2020 Organising Committee and Japanese government decided to stage one Olympic baseball match and six softball games there.

They are even calling the these Games 'The Reconstruction Olympics' in recognition of the power it could have in the disaster-affected areas.

"The recovery of Fukushima isn't something we residents can achieve on our own, we also need the help and efforts of people from outside," says Takahiro Sato, who's in charge of Olympic and Paralympic promotion in the prefecture.

"On the one hand, through the Olympics, we want to show the world how far Fukushima has come. But on the other hand, that we're still facing various challenges.

"Compared with nationwide our foreign tourism is still low. So we want people to see the attraction of Fukushima. By actually coming here they can see that and also try many of the great foods we have here."

The sentiment and objectives are admirable. But 50km south-east of the Azuma Stadium lies the breached Daiichi nuclear reactor and exclusion zone.

And given that radiation did spread from the facility, the question of visitor and athlete safety is only a natural one.

Works are being carried out on the Azuma Stadium in readiness for next year's Olympics

In Tokyo's Shibuya area, FabCafe is a single-origin coffee shop where you can also have all of your 3D printing and laser cutting needs serviced 'while-u-sip'.

It's the ground floor of an office block that's home to floors of 'creative lounge space' where various small, disparate companies and projects are being developed in its open-planned environment.

In one corner is a workbench bedecked with circuit boards and soldering irons. An American steps forward to welcome me.

Azby Brown is a New Orleans native who's studied and lectured in architecture in Tokyo since the 1980s.

He's also a volunteer at Safecast, a non-profit citizen science organisation set up in the wake of the disaster.

"Life changed in 2011 for a lot of people. I felt compelled to step up and try to help," he says.

Safecast, external developed a self-assembly Geiger counter kit, which constantly pools readings for their open-source online database of radiation levels around Fukushima.

Safecast is an international, volunteer-centered organisation devoted to open citizen science for the environment

Brown says the motivation was to fill a gap of information - and trustworthy information - at a time when he says more official sources were confusing and at times erroneous.

"The government has said they wanted the Games there in 2020 and so a lot of decontamination and preparation had to be done," he says.

"But I kind of feel it's a bit rushed and I totally understand why people might not feel comfortable. If a person in Japan themselves is not sure it's OK, then how is an overseas visitor going to feel comfortable?

"I don't think the government has done a very good job of giving people the information they need to make those judgements."

Safecast's citizen volunteers have aimed to provide the clarity they felt was missing with 'scientifically valid' data readings.

Brown and his colleagues also feel that their information allays those safety concerns around Fukushima's suitability to stage Olympic events.

"Fukushima does have residual radiation left over from the accident," he says, "But the places where the Olympics are going to be held like Fukushima City and Azuma Stadium are pretty much normal.

"There's never no risk but the levels are lower than some cities in other parts of the world. People don't often realise that you can receive 10 times the dose of radiation on a long haul flight than you'd get in most places in Fukushima.

"You'd have to go into the exclusion zone - where you often can't get permission to enter - to get a similar dose.

"So by spending 8-10 hours on a flight you'd get more natural cosmic radiation than even a couple of days where the Olympics will be held in Fukushima.

"People are also sceptical about the food and most of our team members are convinced that the food there is safe as well."

By way of back-up, Brown's colleague Louis Elstow, an English academic studying how people live in radiation-contaminated areas, shows me some photographs of a food-monitoring station in a recently re-opened village that was previously off limits.

The machines installed in community centres allow locals to test whether their locally-sourced produce is within acceptable radiation levels for consumption.

Once tested a screen shows a simple circle for 'safe' or a cross for 'unsafe'.

It's a facility that Mr Kumagami might find useful.

"I offer to send my daughter some of the lovely fruit we grow here but she says they won't eat it," he says.

"It's nonsense, but they refuse."

As someone whose life, even eight years on, continues to be affected by the events and perceptions that remain from the earthquake of March 2011, what's his take on the Olympics coming to Fukushima next summer?

"I'm grateful for the idea that they're trying to help Fukushima's recovery by giving it a chance to showcase itself.

"If people from lots of different countries come here and enjoy themselves I do believe it will be helpful to our recovery."

If foreign visitors can discover another side to Fukushima at the Olympics then maybe people closer to home might feel more comfortable visiting as well.

Parts of Fukushima are still contained within an exclusion zone to protect from radiation

Mr Kumagami outside his new apartment