Ramadan in sport: How do elite sports stars cope with fasting?

- Published

Sbihi and his men's eight crew took silver in the European Championships in May

Rowing World Championships | |

|---|---|

Venue: Lake Aiguebelette, France. Dates: 30 August- 6 September |

Could you survive from sunrise to sunset without eating or drinking? Could you do it for 30 consecutive days?

Could you do it while spending almost every one of those days - from 7am to 4:30pm - rowing thousands of metres and lifting weights in the gym?

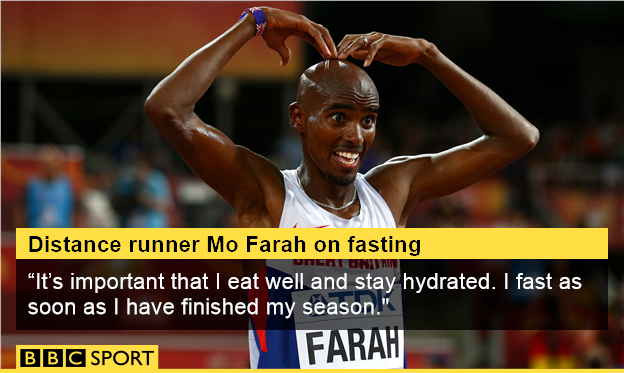

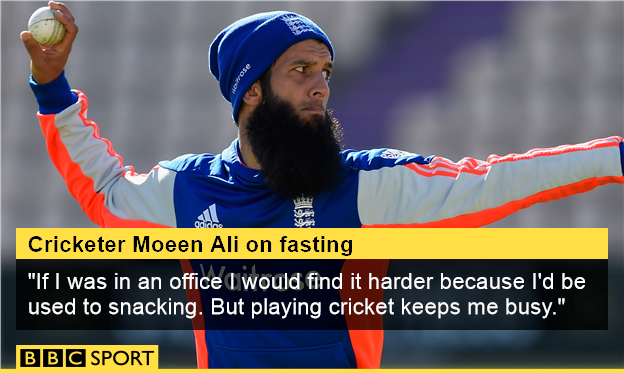

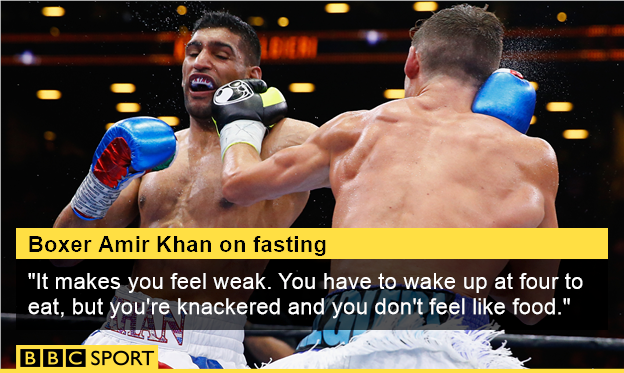

Moe Sbihi does. Like fellow Muslim sports stars Mo Farah, Moeen Ali and Amir Khan, the Great Britain rower observes Ramadan each year.

Ahead of Sunday's final of the men's eight at the World Championships in France, the 27-year-old explained how religion affects his life as a competitor in one of the most gruelling Olympic sports.

What is Ramadan? 'A very charitable month'

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, when Muslims attempt to give up all their bad habits.

"No eating, drinking, swearing, insulting, engaging in sexual relations, smoking," explains Sbihi of a period that shifts according to the movement of the moon but has, in recent times, been over the summer months. This year it began on 18 June and ended on 16 July. "It is a very charitable month in which you, as a family, help the poor and the needy."

Muslims believe any positive actions bring a greater reward as the month has been blessed by Allah. Some will pray more, while others will read the Koran - the central religious text of Islam - more frequently.

But it is obligatory for every able Muslim to fast - which means they must abstain from drinking or eating anything from sunrise to sunset.

What can you eat and when? 'I sit in the dark devouring pastries'

Sbihi, born in Kingston upon Thames, completed his first full fast at the age of 11, while growing up with his Moroccan father and English mother in the London suburb of Surbiton.

"You don't have to do it until you are 14 or 15 - when you hit puberty basically - but even when I was younger I would wake up, have breakfast, then fast the rest of the day with my dad," he recalls.

Sbihi fasted with his family each year until 2010, when it became apparent that he would be unable to observe Ramadan and row at the same time because of competition commitments. Instead, he makes up the days during his winter training blocks.

"They are shorter days so it is a little easier," he admits. "But it's still pretty uncomfortable trying to get fluids and food down when you are bloated and half asleep at 4am.

"I sit down in the cold and the dark with a table full of cereal, milkshakes, pastries, flapjacks… sweet, calorie-rich food that's great to eat once but not every morning at 4am for 30 days. It's a big effort to force it down."

What are the consequences? 'Wow, he stinks'

It's not abstaining from food that Sbihi finds the most difficult aspect of Ramadan. He's "quite a big boy" - at 6ft 7in and 16st 3lb - so has enough protein in his muscles to cope without his usual daily intake of 6,000-odd calories.

Instead, it's the inability to drink anything during daylight hours.

"One of the biggest things about training is the cotton mouth you get and that leads to smelly breath," he explains. "If you catch me on a bad day you might think 'wow, he stinks'.

"The whole thing can cause a lot of frustrations but it really does work as a cleanse and detoxes you."

Does it affect performance? 'I've matched my PB while fasting'

For an athlete who routinely consumes more calories a day than some people do in a week, gorging on sweet treats at 4am is surely scant sustenance for a long day's graft.

"Every year people expect my performances to dip but, actually, I've matched my personal best while fasting and that was at the end of a long day of testing," the Londoner says.

Sbihi admits lethargy and concentration can be a problem but, having completed a dissertation on the subject as part of his sports science degree, he insists any physiological difficulties are outweighed by the psychological benefits.

"My research showed that if you perceive you are at a disadvantage, then most people actually try that little bit harder and that minimised the effects of the fasting. Mind you, all of the other research out there suggests that if you are dehydrated by 2%, your performance will decrease...

"For me, it's a challenge and maybe that has made me better, having to perform in that situation."

Sbihi usually has a daily intake of about 6,000 calories

If Sbihi's colleagues in the eight harboured any concerns about the effect his fasting might have on the boat's output, his performances have removed them.

"We have a laugh and joke about it when they sit down for breakfast in the morning and I'm not eating anything, and I join in with that," he says.

"They are inquisitive more than anything. They want to know why I do it and how I feel, and I've always said to them 'try it' but it's a hard sell.

"We've got 30 guys in the GB team at the Worlds and I don't think many could manage a week, never mind 30 days."

How do you make up for missing it? 'I gave £3,000 to charity'

Sbihi, along with other Muslim athletes in Britain's 2012 Olympic team - double gold medallist Mo Farah, discus thrower Abdul Buhari, and fencer Husayn Rosowsky - opted not to fast in the build-up to London lest their performances be jeopardised.

Sbihi's sacrifice brought a bronze medal as part of the men's eight, rather than the gold he craved.

That disappointment was exacerbated by the fact he had not only abstained from Ramadan that summer - given that it fell during the Games - but was also unable to make up for missing it in 2011 during the preceding winter.

Sbihi, fourth left, and his team-mates had to settle for bronze at London 2012

"An imam [a Muslim religious leader] told me that, for each of the 30 days I didn't fast, I'd need to fast for a month as penance," the rower recalls.

Unwilling to spend two and half years only eating in darkness, Sbihi searched for an alternative in the scriptures.

He discovered - via a cousin in Tangiers and a chance conversation with feted middle-distance runner Hicham El Guerrouj, who also missed fasts during his glittering career - that the Koran would permit him to feed 60 poor people every day for 30 days instead.

He paid for 1,800 meals at a cost of £3,000.

"It's a large sum of money and I'd love to have it back, but knowing why I spent it makes me happy," he says. "It felt important.

"I gave a cheque to a charity called Walou4us, which helps street kids in North Africa, and cash to my family in Morocco to spread about to those who needed it most, because those people would be more likely to accept it from them."

What happens for Rio? 'The bank manager might not be happy'

Sbihi will continue his quest for an Olympic gold in Rio de Janeiro next summer, which means another decision has to be made.

He is due to make up for missing this year's Ramadan over the coming winter - and believes there is a window to do so in November - but appreciates his coach, Jurgen Grobler, may have other ideas given the importance of the next few months.

The pair will discuss the matter after this weekend's World Championships but, if necessary, Sbihi is prepared to get his chequebook out again.

"I'd rather fast but if I need to make a payment again I'll be happy to do it. Even if the bank manager might not be."

- Published5 July 2013

- Published29 August 2015

- Published21 July 2015

- Published5 July 2015

- Published31 August 2014

- Published5 April 2019

- Published19 July 2016