Maurice Lindsay: Rugby league's 'most influential figure of a generation'

- Published

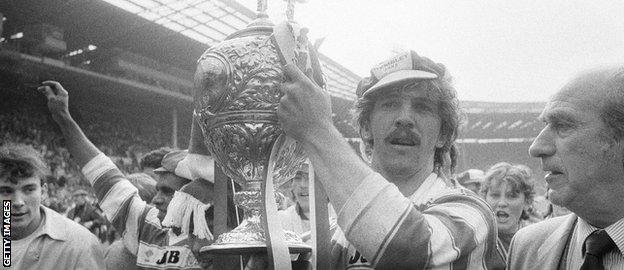

Maurice Lindsay with the three members of the 'Gang of Four' that drove Wigan to success

Maurice Lindsay was undoubtedly the most influential figure in rugby league of his generation - and possibly any other.

Lindsay was the driving force in turning Wigan into arguably the world's most famous rugby league club.

He was also chief executive of the Rugby Football League who steered the game's switch to summer rugby and ushered in the Super League era.

Inspired by Wigan's greats

Born and raised in Horwich, near Bolton, he became a rugby league fan in his boyhood, watching the great Wigan team of the 1950s and 1960s that included the likes of Billy Boston and Eric Ashton.

However, it was not until the early part of the 1980s that his influence in the sport began.

Lindsay, a rails bookmaker, together with local businessmen Tom Rathbone and Jack Robinson and former star player Jack Hilton, formed the so-called 'Gang of Four' and took control of Wigan, after the club had been ignominiously relegated for the first time in the early 1980s.

With a policy of signing the best locally produced players - a 16-year-old Shaun Edwards signed for the club live on breakfast television - and bringing star names to Central Park, the new regime began turning around Wigan's fortunes.

The Cherry and Whites reached a first Challenge Cup final in 14 years when they were beaten by Widnes in 1984.

However, the following year they beat Hull FC 28-24 in one of the most thrilling finals Wembley had witnessed, and the path to success had begun.

Stars attracted through Lindsay's 'Midas touch'

Brett Kenny's skill and thrilling running helped Wigan to a first Challenge Cup in 20 years in 1985

Inspiring the team that day was big-money signing Brett Kenny, the Australia international who Lindsay had tempted to move to England on a short-term basis.

Lindsay's 'Midas touch' when it came to big signings and big publicity saw Wigan recruit some of the best coaches in Australia in Graham Lowe and then John Monie.

On the pitch, there was the world record-breaking signing of Martin Offiah for £440,000, and the return to their home town of many of the talented Wiganers who had begun their careers elsewhere such as Joe Lydon and Andy Gregory.

Wigan became the first fully professional club in the winter era and assembled a side that stood head and shoulders above any other team in England.

Between 1988 and 1995, Wigan won eight consecutive Challenge Cups and multiple silverware in the shape of championships, Regal Trophy triumphs, Premiership final successes and Lancashire Cups.

They also lifted the World Club Challenge crown in 1987 by beating Manly at Central Park, a match that Lindsay had made happen, played in front of a crowd of nearly 37,000.

Unpopular at times, but decisive

Maurice Lindsay helped push northern hemisphere rugby league into a new summer era

Lindsay moved on to the RFL as chief executive and sometimes drew criticism for riding rough-shod over the opinions of others in order to steer the game in the direction that he thought best.

In turn he was sometimes frustrated by not having the autonomy in running the game that he had when he was running Wigan.

In early 1995, at a meeting of clubs to discuss the merits of a switch to summer rugby, then-RFL CEO Lindsay announced he had been in discussion with Rupert Murdoch's News International Corporation.

The revelation was that Murdoch was willing to invest multi-million pounds into the British game to set up a Super League to match the Australian Super League that he was also funding.

Over the next few weeks, Lindsay became a hate figure amongst many supporters after it emerged that for some clubs to join the new league, they would have to merge.

Featherstone, Castleford and Wakefield were slated to become Calder, Humberside set to fuse the two Hull clubs, and Salford and Oldham teed up for a rebrand as Manchester, to name but three examples.

No mergers took place in the end, but Lindsay's role as a divisive figure at the head of the game was set.

He did, however, deliver what he had promised, and the new Super League launched the following year.

Lindsay's legacy remains

Lindsay's thoughts on the game's position and stature led him to produce a blueprint for the direction in which he felt the game's structure and off-field set-up should develop, dubbed 'Framing the Future'.

While not everything recommended materialised, it led to clubs becoming more professionally run and facilities at some, though sadly not all, grounds being improved.

There was scrutiny from his detractors, while he was often able to deflect criticism with his larger than life presence and quick wit.

When an investigation revealed his huge expenses account, including stays at the best hotels in London and an expensive car, paid for by his employers, Lindsay retorted: "You can't have the chief executive of the RFL going to work on the number 57 bus!"

His power in the British game was matched by his influence overseas. Lindsay was respected and admired by the game's rulers in Australia and he was a key figure on the International Board for most of his career.

Ill health and political infighting saw his influence in the game diminish but his legacy remains.

From bursting into the limelight 42 years ago and right throughout his career, he was a man who made a huge difference in rugby league.

Sport's transgender conundrum: What happens next as sport wrestles with a complex balance of inclusion, sporting fairness and safety?

How do you become a football manager? Former Preston North End, Leeds United and Sunderland gaffer lets us in on the secret