Joost van der Westhuizen: Still fighting on his deathbed

- Published

- comments

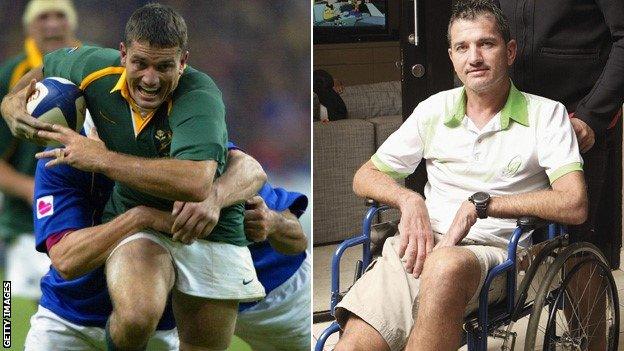

Joost van der Westhuizen was the archetypal Springbok, an Afrikaner whose name became a byword for brilliance, total commitment and supreme physicality.

Now the 42-year-old is confined to a wheelchair, struggles with his speech and barely has the strength to hold a sandwich or lift a drink.

For the last two years his body has been ravaged by the debilitating effects of motor neurone disease,, external which has taken control of everything except his mind. That remains as sharp as ever, but his body has become increasingly disobedient, making every day a challenge.

Van der Westhuizen admits he is on his "deathbed", having been given between two and five years to live when he was diagnosed in 2011., external

Speaking on the telephone from his home in South Africa, it is difficult to understand what the 1995 World Cup winner and holder of 89 Test caps is trying to say.

His speech is slurred and muffled but you can just about decipher his sentences, so that we know the Springbok great is at peace with himself and his situation.

"I realise every day could be my last," he tells BBC Sport. "It's been a rollercoaster from day one and I know I'm on a deathbed from now on.

"I've had my highs and I have had my lows, but no more. I'm a firm believer that there's a bigger purpose in my life and I am very positive, very happy."

Van der Westhuizen, widely regarded as one of the greatest scrum-halves of all time, now lives in Johannesburg with his friend David Thorpe. Together they run his J9 Foundation,, external a charity that raises awareness about motor neurone disease.

The former Blue Bulls, external player first noticed something was wrong at the end of 2008, when he felt some weakness in his right arm.

He presumed it was an old rugby injury flaring up and paid little more attention to it. Then a few months later he was play-fighting in a swimming pool with an old friend, Henry Kelbrick, who is also his personal doctor, and the weakness in his arm became even more apparent.

It was clear this was something much more serious than he had previously thought.

Van der Westhuizen, with his son Jordan and their dog Buddy, says he now realises what's important in life

"Kelbrick identified something, so he rang me up later and asked me to come in that afternoon," he said. "He apologised to me, and then he told me what it was."

The diagnosis was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, one of the most common forms of motor neurone disease.

"First of all I asked him to give me medication, but then he told me about the severity of the condition and that it was terminal."

Van der Westhuizen concedes "it's sometimes difficult to stay positive and motivated" after being diagnosed with a fatal illness. But as a devout Christian, his faith and family have played a big role in helping him come to terms with his condition.

And he says the disease has actually helped him to become a better person.

In 2008 he suffered a suspected heart attack and not long afterwards was at the centre of a sex-tape and cocaine scandal which led to the break-up of his marriage to the singer Amor Vittone., external He also lost his job as a television pundit with the South African broadcaster Supersport., external

"What I did went against all my principles - my life was controlled by my mind and I had to make my mistakes to realise what life is all about," he said.

"I led my life at a hundred miles an hour. I've learned that there are too many things that we take for granted in life and it's only when you lose them that you realise what it is all about.

"But I know that God is alive in my life and with experience you do learn. I can now talk openly about the mistakes I made because I know my faith won't give up and it won't diminish.

"It's only when you go through what I am going through that you understand that life is generous."

For Van der Westhuizen, life is now chiefly about spending time with his family. He has two children, Jordan, seven, and a five-year-old daughter, Kylie.

He is also committed to helping people with motor neurone through the J9 Foundation and plans a visit to the UK in the autumn to watch his beloved Springboks in action against Wales and Scotland.

The sport he loves has also looked out for one of its own.

"When I talk about the rugby community I am talking about everyone in the sport and I have to say they have been brilliant," he says.

"All the number nines I played against in internationals have been phenomenal. Rugby is a big family."

Memories of his distinguished playing career are a source of comfort and satisfaction for Van der Westhuizen. The highlight was obviously 1995, when he was an integral part of the Springbok side that won the World Cup on home soil in front of new president Nelson Mandela., external

His brilliant performance was characterised by a famous tackle on Jonah Lomu, when New Zealand's talisman was going at full tilt after scything past South Africa's captain Francois Pienaar.

He went on to win the Tri Nations in 1998 and captained the Boks at the 1999 World Cup, when they were beaten in extra time in the semi-finals by eventual winners Australia.

The only thing missing on his illustrious CV is victory over the British and Irish Lions. The Boks were favourites to beat the Lions in 1997 but lost the series 2-1. One of the iconic moments actually involved Van der Weshuizen, but not in a way he would have intended.

It occurred in the first Test, when he was one of the players who fell for an outrageous dummy by Matt Dawson, who then went over in the corner for a crucial try,

When he retired in 2003, Van der Westhuizen was the most capped South African player of all time, with 89 appearances, and had scored 38 Test tries, which was a Springbok record until it was recently broken by winger Bryan Habana.

Despite his brilliant record, the former scrum-half is not afraid to laugh at himself, or show humility.

"Everyone still talks to me about that tackle on Jonah Lomu in the 1995 World Cup final," he says, "but every time people mention it, I have to remind them about how I fell for Matt Dawson's dummy in 1997."

That was a rare misjudgement from one of the best players of all time. The archetypal Springbok admits he made mistakes in his life after rugby, but is now finally at peace.