Stuart Lancaster: England reign was not meant to end like this

- Published

- comments

The rise and fall of Stuart Lancaster

What started with such optimism on a fresh day in the New Year ended on a November lunchtime amid recrimination and remorse.

Stuart Lancaster was the obsessive planner who failed to see this coming, the workaholic who gave his all but did not have enough of what ultimately would prove decisive.

When he became England head coach almost four years ago, it was not meant to end as it did - out of a home World Cup a mere three matches in, his final game a meaningless victory over minnows Uruguay with a mish-mash team in a tournament that had already moved on.

Because Lancaster, whatever else he lacked, had a vision: a team loved by its supporters, a team feared by its opponents, a success on the pitch driven by the culture off it.

He looked as straight-laced as the PE teacher he used to be. White polo shirt, buzz-cut, navy tracksuit bottoms, trainers. In the black diary habitually carried under one arm came the funkier stuff.

There was the emotional: giving each of his players a letter written by their parents and added to by coaches, teachers and friends, telling them what it meant to see them playing for England.

There was the inspirational: talks from Gary Neville and Sir Bradley Wiggins, visits from British Army veterans and coaching sessions with junior players.

At the games it was like never before. Stopping the team coach in Twickenham's West car-park so the players walked to the ground through a tunnel of their own supporters.

A plaque next to each peg in the changing-room inscribed with the names of England legends who had played the same position. A huge St George's Cross in the corridor leading to the pitch that was made up of texts and tweets from supporters across the country.

Chris Robshaw (second left) led England for 42 of Lancaster's 46 Tests in charge

It was all lovely stuff. For a while it seemed to matter. Then the more prosaic sporting truths kicked in.

On the ceiling of England's changing-room hung a large disc picked out with five illuminated words: teamwork, respect, enjoyment, discipline, sportsmanship.

No mention of speed, or precision, or tactics, let alone winning.

Lancaster believed all of that would follow. His favourite book, and one he kept on his bedside table, was written by former San Francisco 49ers coach Bill Walsh: The Score Takes Care Of Itself.

For Walsh, blessed with the extraordinary talents of quarterback Joe Montana, wide receiver Jerry Rice and running back Roger Craig, it did. For Lancaster it proved a cruel illusion.

Culture? Before the World Cup he lost Manu Tuilagi and Dylan Hartley to acts of violence, one off the pitch and one one it. His team never really replaced them.

After the tournament it became just as chaotic as it had in 2011: the storm over Sam Burgess' inclusion and then emigration, revelations of player discord, exposure of cracks and criticism in what was supposed to be a rock-solid unit.

Unknown himself to the wider sporting public when handed the reins, Lancaster banked early credit by giving similarly callow and unfamiliar players a chance too.

His first squad contained eight uncapped players, including Ben Morgan, Joe Marler and Owen Farrell. Later he would pick George Ford, Joe Launchbury and Anthony Watson at a similarly young age.

Maybe any coach would have done. Ford was the 2011 world junior player of the year, hardly a bolter. Of Lancaster's first squad of 32 only 12 made it to the World Cup, one of the reasons why his stated aim in 2012 to have a team by 2015 containing 600 caps fell so short.

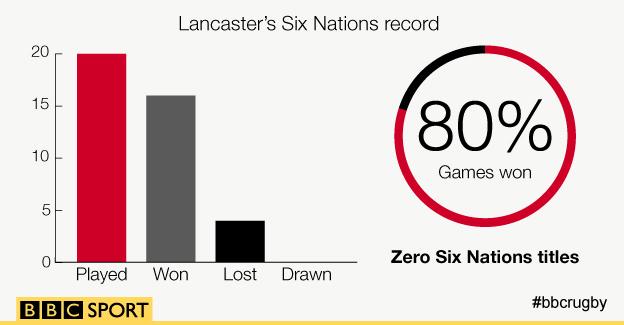

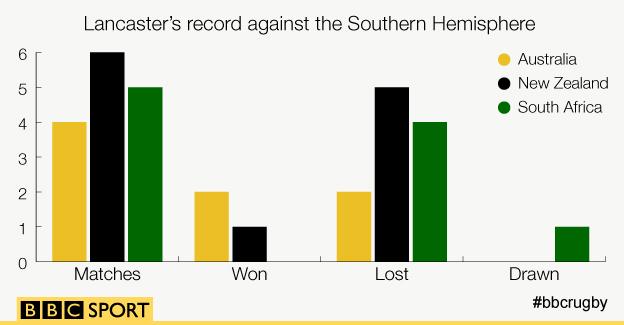

More damagingly, each Six Nations brought a defeat and every autumn at least one more. When the big reverses came - the 30-3 thrashing in Cardiff in 2013, losing yet again to the Springboks in 2014 to make it five defeats on the bounce - the usually imperturbable coach was taken aback by the pressure that came with them.

He would go for midnight runs around the streets of England's training base in Bagshot to clear his head, but the closer the World Cup came, the more muddied his thinking became.

England ended this year's Six Nations with 18 tries, nine more than anyone else. Despite that, the key men in that system and then the attacking philosophy that bound them was jettisoned when Wales and Australia came calling.

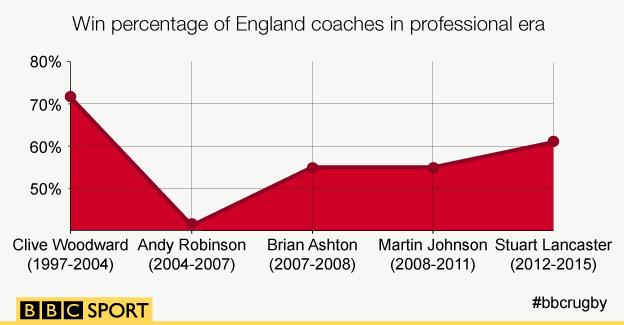

Lancaster had been seen as the antitheses of predecessor Martin Johnson: one a big name but never before a coach, the other an outsider who had coached his way up from the grassroots.

It was inaccurate and ultimately misleading. Lancaster was both an RFU insider (he had been head of elite player development as long ago as 2008) and desperately short of experience at the very highest level. Never before had he been to a match in South Africa, at the Millennium Stadium nor the Stade de France.

The hope was he could both learn on the job and surround himself with experts. Initially he appeared to have done just that. Andy Farrell brought an aura and enviable playing record from rugby league and a promising start at Saracens, Mike Catt enormous World Cup experience, Graham Rowntree the endorsement of the previous regime and Lions.

Compared to those he was up against, it was still raw material. Lancaster had one season in the Premiership with Leeds behind him. Warren Gatland came to the World Cup having coached Connacht, Ireland, Wasps and Waikato and with two Grand Slams and a World Cup semi-final to his name with Wales.

Australia's Michael Cheika won the Heineken Cup with Leinster and the Super Rugby title with the Waratahs. New Zealand's Steve Hansen had coached at Canterbury and Wales and been assistant All Blacks coach for seven years.

His overall record in charge is not in itself damning. He won four of his first five matches; Johnson lost five of his first seven, while Sir Clive Woodward's first win did not come until his sixth game in charge.

But he lost the big matches - a Grand Slam decider, a World Cup must-win match - and he lost repeatedly at what was supposed to be Fortress Twickenham, eight times to Woodward's four.

His strenuous efforts with the media (shaking hands before interviews, phoning journalists to explain key decisions, inviting others to team dinners) were both appreciated and advantageous, perhaps until the end protecting him a little from more critical scrutiny.

His attitude towards previous regimes and players was harder to justify. There had been issues with the team he inherited, but at least they won the Six Nations title and reached a World Cup quarter-final, albeit from a group that contained Argentina and Scotland rather than Australia and Wales.

And insisting that he was instilling new pride in wearing the white jersey when that team included kamikaze patriots like Lewis Moody and Jonny Wilkinson was misjudged at best.

Was it all his fault? While he got key selections wrong - 18 combinations of fly-half and centres, still no-one sure of his preferred option - those who appointed an international novice can also be questioned.

Rugby union commentator Ian Robertson on BBC Radio 5 live |

|---|

"England had a desperately disappointing World Cup. Lancaster had lots of highs, but the World Cup was a bitter disappointment for him, the England team and its followers. |

"Name a qualified English coach who could take over and do a better job? I can't name you one. If for the first time ever England go for a foreign coach the obvious answer is Eddie Jones, who took Japan to three wins out of four - including beating South Africa." |

Lancaster had hoped to be given a second chance, as Woodward was after World Cup disappointment in 1999 and Graham Henry after the All Blacks were stunned by France in the quarter-finals of 2007.

But his case was different. New Zealand's defeat was such a shock because of their track record for the preceding four years had been so outstanding. They suffered one defeat, to an inspired team. Henry had already coached Auckland, the Blues, Wales and the Lions. Woodward had been in the job just two years; his team lost away in Paris, not twice in the group stages on home soil.

England had a slogan under Lancaster: "Hundreds before you. Thousands around you. Millions behind you."

It was both laudable and true. In the end it mattered less than 15 Welshmen three points ahead. By the time the World Cup ended, England long forgotten, the gap between his side and the best in the world had become a chasm.

- Published11 November 2015

- Published10 November 2015

- Published4 October 2015

- Published14 September 2016

- Published15 February 2019