New Zealand v Australia: Can perfect 10 Dan Carter exit in style?

- Published

- comments

Carter has been instrumental in New Zealand's decade-long reign as the world's number one-ranked team

Rugby World Cup final - New Zealand v Australia |

|---|

Venue: Twickenham Date: Saturday, 31 October Kick-off: 16:00 GMT |

Coverage: Commentary on BBC Radio 5 live; live text commentary on BBC Sport website, app & mobile devices |

In the Hollywood version of sporting finales, the great champion always comes through - off the ropes maybe, scarred and exhausted, yet somehow surmounting all odds and opposition to pull off the great redemptive victory and give us all a perfect happy ending.

Not so in the messier, nastier real world. Roberto Baggio missed his penalty in the 1994 World Cup final. Don Bradman fell for a duck in his last Test innings. Paula Radcliffe was beaten by injury at the Olympics in Beijing and then a second time in London, eight years on from the marathon defeat that left her broken on a lonely Athens pavement.

Fair comes second to fate again and again. Which is why, despite so many other alluring sub-plots, this weekend's Rugby World Cup final feels like the defining match in the life of a man who already runs with the immortals.

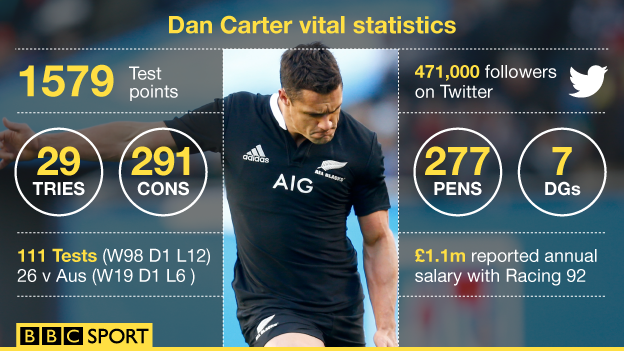

Dan Carter took his first sporting steps as a six-year-old with the Southbridge Midgets, buried away in the backwaters of South Island. In the 27 years since his rugby debut, he has grown into a giant of the game: 111 caps, IRB player of year in 2005 and 2012, scorer of more international points than any other man.

"The most complete fly-half we've ever seen," reckons fellow Kiwi fly-half legend Andrew Mehrtens. "Number one in the pantheon," says Australia's great World Cup-winning 10 Stephen Larkham.

Saturday marks Carter's last All Blacks appearance, one final charge alongside his fellow old warriors Richie McCaw, Ma'a Nonu and Conrad Smith. Those other three can all claim to be World Cup winners. Carter, despite the medal he picked up in 2011, does not feel he can.

Four years ago, while taking the last of his four practice kicks in training the day before the pool game against Canada, he collapsed to the ground after pulling his groin. And while he stayed in camp as his team-mates pushed on to the summit, that was his dream gone: poster-boy reduced to water-carrier, leading man to long-gone extra.

"I was forever asking the 'why' question," he has admitted since. "Why me? Why now?"

An untimely groin injury suffered in training denied Carter the chance to play in the knockout stages of the 2011 World Cup

A second chance has come around at the death with what can feel like celestial serendipity. This is a man who has averaged 14.23 points a game across the 12 years of his international career, not far off double that of the most prolific northern hemisphere points scorers of this era, Leigh Halfpenny and Jonny Sexton.

New Zealand's 1987 World Cup winner Grant Fox, the only other man in history to average more than 14 points a game, did so from 46 Tests rather than more than a hundred. He scored one Test try to Carter's 29. Of the other all-time great fly-halves, Jonny Wilkinson is 333 points behind and 22 tries back, Michael Lynagh 650 points and 12 tries off.

The comparison to Bradman is a valid one, and not just for owning an untouched average. While Bradman grew up in sleepy Bowral, honing his talents by hitting a golf ball with a cricket stump in his parents' back yard, Carter's own bucolic upbringing in rural Canterbury saw him first break every window in his parents' house, trying to clear the roof with his place kicks, and then profit from his father's decision to stick a home-made set of rugby posts on the strip of land alongside.

"He was a phenomenally talented kid, with all the skills, and a keenness and youthful energy," says Mehrtens, who watched the young pretender come into the Crusaders side and in time usurp him at both Super Rugby and international level.

"The hardest thing for a player as the years pass is feeling like you're keeping up with the pace of change in the game, particularly the speed and intensity of it.

"The big matches are not an issue. You can always get up for a game, because you love it. Maintaining that enthusiasm and energy in the slog of training, when you're doing the same thing day after day, is much harder.

"As you get older you have to put in more work to maintain your fitness. He has had serious injuries too. To have come back from all that and still be performing at the level he is today is pretty incredible."

Like Bradman, Carter has gone on to establish records that may never be touched. Like the Australian, he redefined what most thought was possible in his position.

Wilkinson had set new standards in being a fly-half who could tackle like a flanker. Larkham, the Englishman's rival in the World Cup final of 2003, could slice through a defence with speed and step, and pass like few before.

Carter combined that in one explosive package. From his All Blacks debut in 2003, when as a 21-year-old he scored 20 points to put Wales to the sword while playing at inside centre - where he won his first 11 caps as a starter - his unholy mix of pace, passing, defence, tactical acumen and peerless kicking set him apart, never more so than when eviscerating the Lions with 33 points in the second Test of 2005.

Yet being blessed with talents like few others has not insulated him from sport's capricious cruelties. In 2007 he could not turn back the blue-shirted tide as France shocked favourites New Zealand in the World Cup quarter-finals and was forced off injured inside the hour; in 2013 his 100th All Black appearance lasted for only 25 minutes before injury intervened again.

This time the party can expect another Pooper. The Wallabies might have won only one of their past 12 Tests against the All Blacks, but in that 27-19 victory three months ago came the debut of the David Pocock/Michael Hooper back-row partnership, a combination that has both revolutionised Australia's approach and threatens to cut Carter's supply before he can even hope to flourish.

Then there are the challenges of a more unassailable opponent still, the onrushing years.

Carter, now 33, is not the same player he was when the World Cup came calling in 2011, let alone the black-shirted hurricane of 2005. Injuries have slowed his swagger, the subsequent pursuit of old form taken longer to reach fruition. Had Aaron Cruden not succumbed to a serious knee injury, he might not to be starting on Sunday at all.

Wilkinson was 28, a full five years younger, when his own second coming carried England to the final in 2007. By 2011 he was an unhappy imitation of his revolutionary self as England fell apart in the quarter-finals.

Andrew Mehrtens and Dan Carter enjoyed success with Canterbury and Crusaders before Carter succeeded Mehrtens in the All Blacks number 10 jersey

Carter too has been searching for the old sweetness and sorcery. In the pool match against Georgia he missed three of his four kicks. Only against France in the quarter-final was the old flair evident once again; only in the attritional slog of the semi-final did he appear to have the old control back, with that critical conversion from way out wide and drop-goal from distance with his side five points down and a man short.

Like Roger Federer, another sporting genius of similar age fighting the same battles with diminishing resources, he is finding consolation elsewhere.

"When Dan burst onto the scene and played those amazing games against the Lions in '05, he was able to showcase his individual skill," says Mehrtens.

"But as you get older, you get more and more into the mode of directing your team around and orchestrating the game. It's very easy to lose sight of yourself as an attacking threat, to get out of the habit of just passing the ball on and manoeuvring others.

"That's not Carter being lazy, that's the role you go into. It's not a conscious decision not to use yourself in attack, but you get into the habit of shifting it on. And he picks his moments really well, and he makes them count.

"When people criticise Carter for not running as much as he used to - well, when he steps on it and has a crack, he still has the pace. He just makes sure it counts, as he did against France."

It may not be as flashy as it once was, just as Roger Federer cannot destroy opponents with that forehand as he once could or shrink distance with that sweetly deceptive speed of old.

Dan Carter and Richie McCaw have been lauded as the best players of their era, and two of the all-time greats

But the wizardry is there when he calls on it, even if it is less obvious to the casual eye. Pocock's destruction at the breakdown is the heavy artillery. Carter's speed of thought sets the cavalry loose.

"The way you can judge a really good fly-half is the confidence he gives to guys around him," says Mehrtens, whose record Test aggregate for New Zealand Carter surpassed six years ago.

"Their timing looks perfect when they're running on to the ball, they're always getting it out in front in exactly the right spot so they don't have to adjust at all, because it is a game of millimetres, and you don't want to adjust at all. You see the effect Dan has on others more than what he does himself."

"He's shown really good composure during this tournament," agrees Larkham. "His skills haven't dropped off at all, he picks and chooses when he wants to run and he does that really well. He's combining with his team-mates very well."

World Cup finals seldom stick to the script. Four years ago New Zealand's triumph was masterminded in the end not by Carter, nor his replacement Colin Slade, or even his back-up Cruden, but by fourth-choice fly-half Stephen Donald, a man who had been summoned from a whitebait-fishing trip and ran onto the pitch for the final wearing a shirt that appeared to be borrowed from a teenage girl.

The All Blacks will be happier with a less complicated final act this time around. Keep the bad guys at bay. Let their heroes do their thing. Make the ending a happy one, for one great champion at least.

- Published30 October 2015

- Published31 October 2015

- Published27 October 2015

- Published29 October 2015

- Published29 October 2015

- Published28 October 2015

- Published26 October 2015

- Published3 February 2017

- Published14 September 2016

- Published15 February 2019

- Published25 September 2015