Racing v Saracens in European Champions Cup: The Zen of Dan Carter

- Published

- comments

Calm, extremely humble, and one of the greatest rugby players of all time...

European Rugby Champions Cup: Racing 92 v Saracens |

|---|

Venue: Grand Stade de Lyon Date: Saturday 14 May Kick-off: 16:45 BST |

Coverage: Commentary on BBC Radio 5 live, plus text commentary on the BBC Sport website |

Sport at the elite level, even for those few geniuses who can routinely do what others can only dream of, typically appears to be about obvious effort and relentless industry.

You try harder, you do better. You feel the pressure and you respond to it. You impose yourself upon rivals through physical dominance and force of personality.

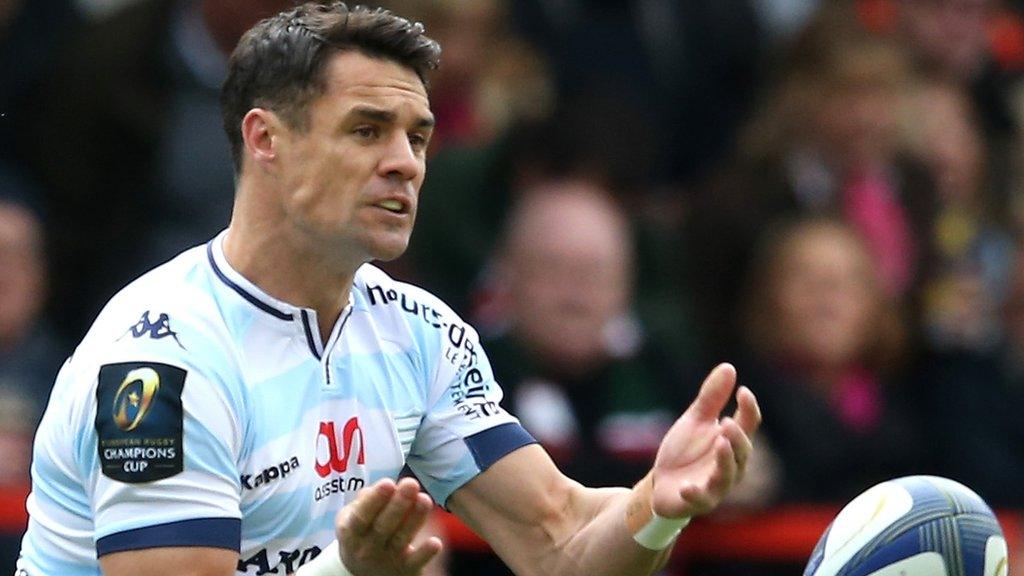

In a sport like rugby union, where players have never been bigger, faster, or hit harder for longer, might is right like never before. Which makes the continual influence of Dan Carter not just illogical but something close to miraculous.

On Saturday evening in Lyon, Carter - the leading points scorer in Test history, reigning World Rugby player of the year, World Cup winner for a second time seven months ago - will, in characteristically undemonstrative fashion, lead Racing 92's charge as they take on Saracens in the Champions Cup final.

Carter collects the BBC's Overseas Sports Personality of the Year award

The All Blacks great is not only a physical throw-back in a game increasingly for the outsized and enormous. At 5ft 10in and 14 stone, the 34-year-old plays an old-fashioned way: finding space where others seek contact, appearing unhurried when fly-halves have never had less time, still managing to play on instinct when set moves and patterns are everywhere you look.

It's not that Carter doesn't do the nasty stuff. In Racing's semi-final win over Leicester Tigers he made 16 tackles.

It's how he does it. Whereas Jonny Wilkinson, the original big-hitting number 10, stopped opposition runners like a rogue flanker and brought gasps from the stands and lungs of the victim alike, Carter tackles like he does everything else - with economy rather than anger, with perfect yet undemonstrative technique, with efficiency over ostentation.

Carter is not quite the player he was. The outside break and sudden acceleration that defined so many of his early masterclasses have quietly been lost to the years. It doesn't really matter. In his swansong he appears to worry less about what he lacks than utilise what he does.

If it wasn't the sort of thing that in his home town of Southbridge would trigger disbelief - expressed, because this is the South Island of New Zealand, by something as flamboyant as a raised eyebrow or muted cough - you'd say it was all rather Zen: the impossible calm in a sporting storm, the balance between self and team, equanimity in even the biggest occasions.

Dan Carter (top) and Jonny Wilkinson (below) share the same drive for perfection but not the same easy-going nature

There is the ritual of his relentless kicking practice, whether at the posts that his father put up next to the family home or on the foreign fields of France; the meditation brought about by those repeated simple actions; the carefully constructed humility of an All Blacks environment where 100-cap heroes like Carter and retired captain Richie McCaw were expected to clean up the dressing room like backroom juniors.

And it is all done in the most unobtrusive way. Wilkinson kicked from the tee with such exaggerated movements that half-cut punters in pubs could do impressions. Dan Biggar has his little soft-shoe shuffle, the 'Biggarena'. Owen Farrell, Carter's opposite number on Saturday, has the laser eyes and robotic head-turn.

Carter? Even after so many penalties and conversions, it's still hard to remember exactly how he looks in sweet motion. The fact that he has been the same with ball in hand - perfectly timed passes or offloads, but all done in the most discreet and understated way - have sometimes made it hard for people to understand what has made him so special. He doesn't always stand out, so how can he be outstanding?

"He's fascinating," admits Ronan O'Gara, arguably Ireland's finest fly-half and now, in early retirement, assistant coach at Carter's Racing.

"He's just extremely humble, extremely respectful. He smiles, he always finds a way of getting the job done.

"He doesn't stress, he's always polite, he's a breath of fresh air. You can learn an awful lot by just watching him."

Dan Carter was the BBC's Overseas Sports Personality of the Year in 2015

Carter isn't the only sporting great who can appear to be operating in slow-motion and fast-forward at the same time, but he maintains that composure longer than most.

Tennis' Roger Federer at his best was both unhurried and unflustered, but at the moment of victory all that held-back emotion would come crashing out. In cricket, Chris Gayle remains expressionless when thrashing unfortunate bowlers for six after six, but will dance with his top off when victory has been won.

Lionel Messi, for all the gossamer touches with that left foot, is all beautiful bustle and obvious energy, Cristiano Ronaldo all strut and preen on the football pitch.

Even Tiger Woods, who before his fall could hold his form and nerve in the final-round meltdown like no other golfer, would spit and cuss his way round the course when the mojo left his side.

Carter, in the biggest moments he has faced, has looked as perturbed as if he were back at Christchurch Boys' High School, from the second Test against the Lions in 2005, when he turned in a performance that led to him being described as "the perfect 10",, external all the way through to last October's World Cup final.

Against the Wallabies at Twickenham that day, there was a moment to epitomise so much of what had come before: the All Blacks suddenly under huge pressure, their 17-point lead cut to just four with 15 minutes to go.

In his first 110 Tests Carter had landed a total of just six drop-goals. A week after adding another to put away South Africa in the semi-finals, he took a pass flat with the defence charging, his feet and eyes set for the short pass to Sonny Bill Williams on his outside shoulder.

Forty metres out, the game's greatest prize in the balance, chaos all around. Not for Carter. Instead, a little pocket of space and tranquillity and time where no-one else could see it, a turn of the shoulders and hips, a perfect contact with his left boot to send the ball arcing between the sticks.

Carter is not just the leading points scorer in Test history, but also in Super Rugby, scoring 1,708 points for the Crusaders

Wilkinson was also touched by Eastern philosophy, first by Buddhism as cruel injuries kept keeping him out, later by a Japanese school of thought called Kaizen.

Because of the man that Wilkinson is, that was more about a tortured form of self-improvement. "You imagine being watched by a video 24/7 to help you get better each day and make good decisions," he has said.

For Farrell, who shares much of Wilkinson's dedication, Saturday is also about a particular kind of personal development.

After his yellow card in the critical World Cup group match against Australia and the two-week ban for a dangerous tackle after Saracens' Champions Cup semi-final win over Wasps, he will be watching Carter not just to keep his influence in check but to learn from the old master too.

"It's just how calm he is, how much he is in control of what he does that stands out," the fiery Farrell says.

"Trying to be calmer on the pitch, it's definitely something I'm always trying to do. The more you're calm, the more you're in control and the more you're thinking about the right things."

Carter in control. The career moves on, but the philosophy remains the same.

For the latest rugby union news follow @bbcrugbyunion, external on Twitter.

- Published9 May 2016

- Published23 April 2016

- Published24 April 2016

- Published3 February 2017

- Published15 February 2019